![]()

Chapter 1

The Rise of Military Robotics

Some people say that the age of robotic warfare began with the attack on a moving car occupied by four terrorists in Yemen in November 2002 (Weed 2002). The attack was carried out by CIA operators with a modified Predator UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle), which fired a Hellfire missile at the car, killing all of the occupants. Although the UAV was flown by a human pilot (from a remote location), who also launched the missile, the incidence gave a glimpse of things to come: the possibility of the complete removal of the human soldier from the battlefield and, at least potentially, also the exclusion of humans from the decision-making loop. Finally – the lethal military robot has appeared on the world stage and had killed its first prey. At least so it seemed. In reality, military robots have been around for a long time and have been used in various guises ever since the First World War (Shaker and Wise 1988, 21–39). The difference is only that the technology is now maturing and that intelligent weapons that can operate successfully with little need for human supervision are now technically possible. The armed Predator drones are only an indication of this general trend and also proof that robots have now reached the point where they can be actually militarily useful (Weiner 2005a).

Robots have aroused human fascination and fantasies for a long time. They have appeared in uncounted science fiction novels and movies. Although much of the present reality of robots is still that of huge computer-controlled arms putting together cars in factory halls rather than the fantastic machines of science fiction, it is also true that the military affinity with ‘robotic’ weapons goes back a long way. Robots always seemed somehow destined to enter military service and to become one day the ultimate weapon: a weapon that no longer requires a human warrior to wield it. In a sense, the military robot could be the perfect warrior: superior in strength and skills and completely obedient. At the moment, we are still far away from robot soldiers, but there is no doubt that robotic systems have proliferated rapidly in the modern armed forces around the world, with much more to come in the next decade. Robotic warfare seems to be just around the corner (Brzezinski 2003).

What Is a Robot?

Great confusion exists about what exactly a robot is. At different times a self-steered steamship, an animated puppet and a computer-controlled arm have all been called robots or robotic machines (G. Chapman 1987). The computer scientist Gary Chapman has pointed out that ‘there is no logical explanation why certain devices are called robots and others are not’ (G. Chapman 1987). The main problem is that the idea of the automaton that can do things a human can do is very old, while the term ‘robot’ only appeared in the early 1920s. From then on any automaton, in particular those imitating humans or animals, could be called a robot. At the same time, science fiction authors were creating the image of the robot as an artificial man that is in many respects equal, if not superior, to a human being. So the term ‘robot’ was attributed to anything from the simple clockwork automaton to the convincing human duplicate of science fiction, with industrial robots occupying the middle ground. The main idea behind robots is that of a useful artificial worker that can free humans of the burden of work. A robot is therefore simply a machine, but it is also a very special machine in the minds of many people, as it is a machine that comes closest to being ‘alive’ or life-like.

In contrast to other machines, which are merely automata, robots are often attributed agency or intent, as they are able to interact with, or even compete with, humans. Sometimes robots are talked about as if they had emotions like desires, or good or bad intentions toward humans. This human uneasiness toward possible robot intentions is indicated by the public response to the first lethal accident involving a repairman being crushed by a robotic arm in Japan in 1981, which received a lot of media attention around the world. The incident was not treated as just another industrial accident, but as a special kind of accident because it involved a robot and not any other ordinary machine. In fact, it was portrayed by the press like a homicide committed by a machine capable of evil intentions (Dennet 1997, 351). Of course, from a purely technical point of view this was hardly a possibility.

So there is this interesting tension in the popular image of the ‘robot’ of being an automaton – a machine that is completely predictable and completely controllable and obedient – and the concept of an artificial man with own intentions and desires and therefore equipped with an inherent capability of unexpected behavior, disobedience and even rebellion. Science fiction authors have skillfully played with this double meaning of the term ‘robot’, portraying them sometimes as obedient machines following the commands of humans mindlessly to the extent that it is even detrimental for themselves and their human masters; and sometimes portraying them as machines that can become self-aware and can suddenly decide to follow their own interests. This double image of the robot created by science fiction writers since the 1920s still affects popular conceptions of what robots are, or might be in the future.

Not surprisingly, there are many relevant definitions of what a ‘robot’ is today, some of which include a greater variety of machines, while others are more restrictive. The Encyclopaedia Britannica defines a robot as ‘any automatically operated machine that replaces human effort, though it may not resemble human beings in appearance or perform functions in a humanlike manner’ (Encyclopaedia Britannica Online 2008). Daniel Ichbiah, who is a renowned robotics expert and enthusiast, suggests that a robot in the early twenty-first century ‘is a very powerful computer with equally powerful software housed in a mobile body and able to act rationally on its perception of the world around it’ (Ichbiah 2005, 9).

Generally speaking and for the purpose of this book, a robot can be defined as a machine, which is able to sense its environment, which is programmed and which is able to manipulate or interact with its environment. It therefore reproduces the general human abilities of perceiving, thinking and acting. So strictly speaking a simple remote-controlled device is not a robot. A robot must exhibit some degree of autonomy, even if it is only very limited autonomy.

Currently there are two basic types of ‘robotic’ machines that are in use by the armed forces: they can be remotely controlled (tele-operated) or self-directed (autonomous) (Bongard and Sayers 2002, 299). In the case of tele-operated machines, the human operator takes over the tasks of perception and thinking for the machine and is in full control of its actions. However, normally a robot would have to carry out at least some functions autonomously, even when generally tele-operated, in order to deserve the label ‘robot’. In other words, they need to be in some form programmable and in some situations able to act without direct control of the operator. This is indeed usually the case with current military robots, although it might be just a ‘return home’ function in case they lose communication with their operator. In the future robots will become more intelligent and more capable of making their own decisions, for example which route to choose or how best to achieve a given objective. But that might also be the point where the similarity with humans stops. In general, robots do not have to be humanoid or possess intelligence similar or even comparable to humans.

In fact, robots can be all sizes and shapes and are at present hardly more capable than fulfilling a rather narrow function for which they were originally designed and programmed. This means that machine intelligence is likely to remain very specific to the task for which a machine was originally designed and not to be as universal as human intelligence (Ratner and Ratner 2004, 59). But the dream of roboticists, however, is indeed the development of a truly universal robot, which could be easily reprogrammed for a great variety of tasks – in other words, make a robot less of an automaton and more of an artificial man. Roboticist Hans Moravec, for example, believes that the eventual development of robotics will be in the direction of universal robots that could rival and even exceed humans in terms of general abilities and versatility (Moravec 1999, 110).

In the future, the meaning of the term ‘robot’ could even become more diverse and confusing than it already is. The director of the Pentagon’s Alpha analysis group on military robotics, Gordon Johnson, has pointed out in an interview that:

The robots [under development by the Pentagon] will take on a wide variety of forms, probably none of which will look like humans … Thus, don’t envision androids like those seen in movies. The robots will take on forms that will optimize their use for the roles and missions they will perform. Some will look like vehicles. Some will look like airplanes. Some will look like insects or animals or other objects in an attempt to camouflage or to deceive the adversary. Some will have no physical form – software intelligent agents or cyberbots. (US Joint Forces Command 2003)

The robots of the future will, like the robots of the present, therefore be quite different from the popular conception of robots and will be more astonishing than the robots of the past. The numbers and variety of robots used by the military are growing and they could change warfare forever. Of course, much of this is speculation, but there are already very clear trends that indicate the growing importance of automation and robotics in many areas of society, not just in warfare. Robots have already become viable in the manufacturing industries and they are now spreading to the services industries. If Alvin and Heidi Toffler are correct in their assumption that ‘the way we make wealth is … the way we make war’ (Toffler and Toffler 1995, 80), then robots will have a major influence on the conduct of war within the next two decades.

The following investigation sticks to the above definition of robots as programmable and sensor-controlled machines and will therefore include a wider range of military systems than are usually discussed in the context of military robotics. The term robot is therefore a description of a particular type of AW (e.g. the autonomous land vehicle), as well as a figurative term for any programmed or autonomous weapon. Another term that is frequently used in the literature on military robotics is ‘unmanned system’. The term usually refers to mobile platforms like aerial vehicles, spacecraft, ground vehicles, or naval vehicles. This means not all robotic systems are unmanned systems (only if they are platforms for weapons or sensors). At the same time, ‘unmanned’ would usually imply robotic and robotic could mean remotely controlled or autonomous. For example, a cruise missile would not be called an unmanned system, as it is not designed to return from a mission (compare US DoD 2005b, 1), but it is clearly a robotic weapon, as it is programmable. The exact meaning of autonomy is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

The Current Robotics Revolution of Warfare

There is little doubt that the interest in developing robotic weapons has substantially grown over the last couple of years. The technology is maturing and the costs are dropping, making military robotics both more viable and affordable for many nations. Robotic systems, especially UAVs, have already proven their effectiveness in recent conflicts, such as the Kosovo air campaign in 1999 and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Their numbers in the US armed forces have risen so dramatically since 2000 that even several years ago few military analysts saw it coming. The number of the Pentagon’s unmanned air systems shot up from 50 to over 5,000 (Gates 2008) and the number of unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) recently surpassed 6,000 (Nowak 2008a). The bulk of the literature on the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) that has been produced since the early 1990s therefore hardly mentions military robots, including some newer titles such as Tim Benbow’s The Magic Bullet, published in 2004. Military robotics is still, in terms of military/strategic thought, in unknown territory. Technological progress is once again outpacing the development of doctrine. With regard to finding effective ways of using the new technology, much currently happens in the field through a process of trial and error.

In particular, the US military will soon be transformed by the current robotics revolution of warfare. US Congress already mandated in 2001 that by 2010 one-third of all combat aircraft shall be unmanned and that by 2015 one-third of all ground vehicles shall be unmanned (US Congress 2001, S.2549, Sec. 217). Furthermore, the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review states that ‘45% of the future long-range strike force will be unmanned’ (US DoD 2006a, 46). The Department of Defense (DoD) has also recently published a report called ‘Unmanned Systems Roadmap 2007–2032’, indicating a long-term commitment to military robotics. According to this report, the US DoD plans to spend more than $24 billion on unmanned systems in the years 2007 to 2013 (US DoD 2007, 10). Its biggest project involving robotics is currently the $300 billion Future Combat Systems program, which relies so heavily on military robotics that some people call it an attempt to field a robot army (Sparrow 2007b, 64).

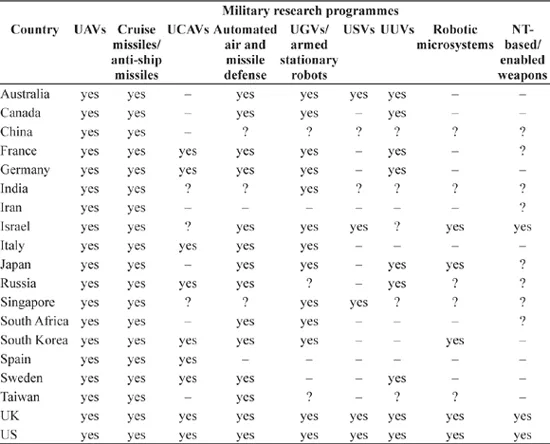

The robotics professor Noel Sharkey from the University of Sheffield claims that the arms race for developing and fielding military robots is already well under way (Minkel 2008). It has been reported that more than 40 nations are currently developing robotic weapons (Boot 2006b, 23). This includes first and foremost the US, but also the UK, France, Italy, Canada, Germany, Japan, Sweden, Singapore, Iran, South Korea, South Africa and Israel. They are working on UAVs, unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs), UGVs, stationary sentry robots, unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) and micro and nanorobots. About 90 nations are believed to have UAVs in their arsenals and about 600 different types are produced worldwide (Conetta 2005, 17). A growing number of states have somewhat less advanced (or less autonomous) robotic weapons, such as cruise missiles and anti-ship missiles. After all, a cruise missile is nothing but a robot plane that is not expected to come back. A report to the US Congress claims that already 75 nations are believed to have such weapons in their arsenals (Feikert 2005).

Most efforts and money are presently directed toward the development of UAVs and UCAVs, which are the type of autonomous robotic weapons system that is closest to actual deployment. UAVs/UCAVs are technologically at least 10 years ahead of UGVs and there are many types either already in the field or in an advanced stage of development. For example, between 1998 and 2006 Boeing developed the X-45 UCAV, of which several prototypes flew successfully. The X-45 was designed to operate autonomously as a reconnaissance and strike platform with the ability to take off, refuel mid-air, respond dynamically to threats, carry out its mission and return to base – all by itself or with minimal human supervision (Tirpak 2005). The US is by no means the only state developing UCAVs; Europe is not too far behind in this field.

The current European UCAV projects include the Taranis and Mantis (UK/BAE Systems), the nEuron (France/DGA) and the Barracuda (Germany/EADS), all of which are expected to enter service in some form or shape in the years 2010 to 2020. Even Russia is trying to catch up in the development of UCAVs with at least two prototypes under development by MiG and Sukhoi (Komarov and Barrie 2008). John Pike sees an expanding role for military robots and contends that ‘we are probably seeing the last manned tactical fighter being built now, and in a few years there will be no manned tanks or artillery’; he also argues that the era of robotic warfare is approaching ‘faster than many people think’ (Arizona Star 2007). So it can be claimed safely that lethal military robots will be introduced in larger numbers by the most technologically advanced armed forces within the next five to ten years. Their exact roles, autonomy, functions and doctrine are still undetermined. Sooner or later military organizations will have to figure out what they want to do with ever more capable unmanned systems and how to use them most effectively.

Table 1.1 gives an overview of military robotics research in 20 countries around the world.

Military robotics is still in its infancy, but it is developing at an incredibly rapid speed. This can be seen in the progress that has been made in developing autonomous ground vehicles over the last few years. In 2004 the Defense Advanced Projects Agency (DARPA) held a competition called Grand Challenge in which autonomous vehicles had to race over a distance of 142 miles. None of the 15 vehicles managed to get further than eight miles (Hallinan 2004), but just one year later in Grand Challenge 2005 there were five finishers. In late 2007 DARPA held the Urban Challenge competition in which robotic vehicles had to drive alongside human-driven cars in an urban environment. There were 11 finalists on the 2.8-mile course and only one crash (US DARPA 2007b). At the very least the three competitions prove the rapid progress in autonomous vehicle technology and may indicate that the autopilot for cars is not far off (Lee 2008). Similar military robotics competitions have been organized in some other countries around the world in recent years.1 This gives good evidence for the military’s interest in unmanned systems and of the rapid development in this area.

However, building military UGVs, which can move as quickly and intelligently over difficult terrain as human-driven vehicles in all weather conditions, evading obstacles and enemy fire while being able to autonomously engage suitable targets, is a lot more difficult than getting autonomous vehicles to obey traffic rules. But few experts doubt that it could be done in principle. So it might be reasonable not to have exaggerated expectations about military robots in the near term, while acknowledging the truly transformational potential of robotics on warfare in the medium to the long term. The autonomous killer robot is not yet here, but there are no technical reasons why it should not arrive in a fairly short time measured in historical terms.

Despite the recent hype surrounding robotics and military robots in particular, it is quite surprising how old the idea of the war robot and robotic weapons actually are. The following section gives a brief historical overview of military robotics, from ancient times to the occupation of Iraq.

Table 1.1 Worldwide military robotics research

The Early History of Military Robotics

The robots that became prominent in the modern science fiction writing of Karel Čapek, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke symbolize the ancient dream of creating an artificial man – however, an artificial man that is far from being considered equal to man. The word ‘robota’ is Czech and means slave laborer – and that is exactly what robots are meant to be. But no man wants to be a slave and to live in fear of their own master. The relationship of man and robot, or creator and creation, has therefore always been seen as a potentially very problematic one.

Robots of Ancient and Pre-modern Times

Creatures appear in many Greek myths that are very similar to our modern understanding of robots. The myths already point at the weaknesses and dangers of robots, which may still be relevant ...