eBook - ePub

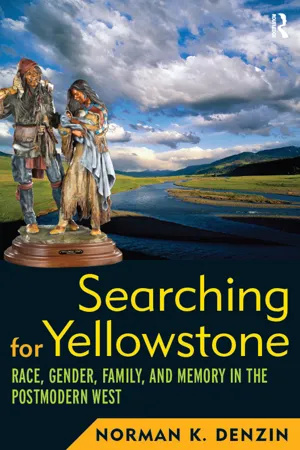

Searching for Yellowstone

Race, Gender, Family and Memory in the Postmodern West

- 255 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Yellowstone. Sacagawea. Lewis & Clark. Transcontinental railroad. Indians as college mascots. All are iconic figures, symbols of the West in the Anglo-American imagination. Well-known cultural critic Norman Denzin interrogates each of these icons for their cultural meaning in this finely woven work. Part autoethnography, part historical narrative, part art criticism, part cultural theory, Denzin creates a postmodern bricolage of images, staged dramas, quotations, reminiscences and stories that strike to the essence of the American dream and the shattered dreams of the peoples it subjugated.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Searching for Yellowstone by Norman K Denzin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Photo Montage 1

MYTHIC NATIVE AMERICANS AND THE NEW/OLD WEST

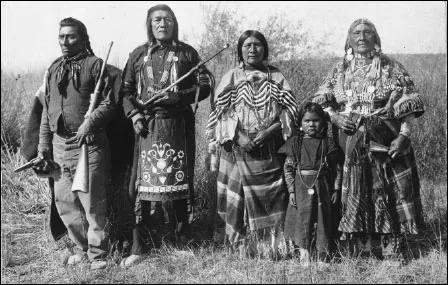

The first three photographs in Montage 1 represent white Americans’ mythic views of Native American women and men, from Sacagawea to Chief Plenty Coups and Chief Illiniwek. These images circulate in the New West in the present. But they are meant to be timeless, existing in a continuous time frame from the past to the present.

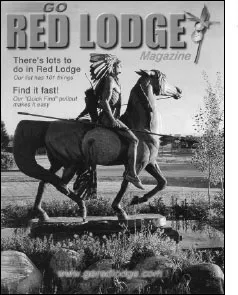

Harry Jackson’s famous bronze statue of Sacagawea (Plate 1) stands in the Cusman Greever Garden at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming (Chapter 5). Chief Illiniwek (Plate 2) is an invented college mascot who has had a troubled history at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana (Chapter 8). Some believe he danced for the last time at a halftime ceremony during an Illini basketball game in February 2007. The statue of Chief Plenty Coups (Plate 3), the last chief of the Crow Indians, greets visitors as they enter Red Lodge, Montana. Chief Plenty Coups State Park is 35 miles south of Billings, Montana.

The five Bannock Native Americans in Setting the Record Straight (Plate 4) were photographed by William Henry Jackson in 1871. This staged photo represents the classic nineteenth-century museum view of Native Americans. The photographer has the subjects dress in native or ritual garb, has them pose, and then claims that the photograph is a realistic representation of male or female Native Americans. Whose record is being set straight?

Plate 1. Harry Jackson’s statue of Sacagawea, Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Plate 2. Chief Illiniwek, “The Last Dance.”

Plate 3. Chief Plenty Coups, Red Lodge, Montana.

Plate 4. William Henry Jackson, Setting the Record Straight, 1871.

Chapter 1

SEARCHING FOR YELLOWSTONE I

“If we do a census of the population in our collective imagination, imaginary Indians are one of the largest demographic groups. They dance, they drum; they go on the warpath; they are always young men who wear trailing feather bonnets. Symbolic servants, they serve as mascots, metaphors. We rely on these images to anchor us to the land and verify our account of our own past. But these Indians exist only in our imaginations.”

(SPINDEL 2000, 8)

“We say that Yellowstone National Park was established on 1 March 1872, but in fact we have never stopped establishing Yellowstone. Whether as first-time visitors or as world-famous biologists, we continue to discover and explore it, and we also continue to create it. That is why I have called this book Searching for Yellowstone; … indeed, the search for Yellowstone is a search for ourselves.”

(SCHULLERY 1997, 2–3, 5, 261–62)

In 1994 my wife and I bought a small cabin on Rock Creek, 4 miles outside Red Lodge, Montana, 20 miles from the Wyoming border, 69 miles over the Beartooth Mountains into Yellowstone Park.1 Red Lodge is at the center of a triangle formed by Billings, Montana; Cody, Wyoming, with its famous Buffalo Bill Historical Center (Bartlett 1992); and the park itself, each about 65 miles apart. We have become cultural tourists in the New West (Limerick 2000), “seasonals” traveling back and forth between Champaign and Urbana, Illinois, and Billings and on to Red Lodge—and to many of the small cities and towns between Red Lodge and the park, including Big Timber, Cody, Cooke City, Gardiner, Livingston, Mammoth Hot Springs, Silver Gate, and, in the park, Tower Junction, Lamar Valley, Roosevelt Lodge, Canyon Village, Yellowstone Lake, and Old Faithful.

THIS BOOK

This book—part memoir, part ethnography, part performance text—comes out of experiences in this complex triangular space. In this tiny slice of the postmodern West, cowboys, Native Americans, park rangers, and cultural tourists collide. In the summers of 2004–2006 the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804–1806 was reenacted. Suddenly our corner of Montana was filled with Native Americans, some dressed as Sacagawea, others as fancy dancers. White males dressed as mountain men reenacted the Lewis and Clark journey. Sacagawea cookbooks sold out at Red Lodge Books. It was as if time had stood still.

In each chapter I encounter these idealized Native Americans and their representations (Huhndorf 2001; Hoxie 2006). These images invoke the idealized authentic, prewhite, historical Native American or the Native American assimilated to white culture, as in the case of Sacagawea. I find myself embedded in these representations, in these narratives: Indians playing cowboys, cowboys playing Indians, twenty-first-century Native Americans playing nineteenth-century Indians, and little white boys playing Indians (Deloria 1998).

I interrogate the emotions, the identities, and the memories that accompany these collisions among white, Native American, and contemporary western popular culture (Lear 2006). These stories connect to my childhood and the movies about the West that I watched with my grandfather. They show how my childhood and family experiences continue to shape what I write about today.

Chapter 2, an autoethnographic performance text, folds family memories into reflections occasioned while watching Crow Indians performing fancy dances for white tourists in Red Lodge. Chapter 3, a four-act play, focuses on the disappearance and reappearance of Native Americans in Yellowstone (see also Christofferson 2007; Nabokov and Loendorf 2004). The three-act play in Chapter 4 interrogates the place of Hudson’s Bay blankets in the Lewis and Clark Expedition. I connect these same blankets, metaphorically, to my family, where they function as gifts that connect one generation to the next.

The play “Sacagawea’s Nickname, or the Sacagawea Problem” (Chapter 5) dramatically explores the sexualized representations of Sacagawea and Native American women in the Lewis and Clark journals as well as in Montana’s foundational novel, The Big Sky, by A. B. Guthrie Jr. (1947). Chapter 6 consists of a historical drama which reenacts the creation of the most famous painting of the park, Thomas Moran’s Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. A Native American male is buried in the center of Moran’s panting. The meanings of this presence are debated in the play.

Chapter 7 offers a more traditional narrative reading of the only known Native American representation of Yellowstone Park, Crazy Mule’s map. Chapter 8, another three-act play, examines the conflicts surrounding racial performances of idealized Native Americans in Red Lodge, Montana, and Urbana, Illinois. Chapter 9 takes up another version of my search for Yellowstone. I work my way back through another set of family memories as well as more recent encounters with postmodern western performances on Rock Creek. The Coda (Chapter 10) comes full circle, locating these stories and performances in the current historical moment.

In each chapter I examine the social and historical circumstances that reproduce racial and gender stereotyping in the contemporary West. At a deep level I write about a search for more realistic utopias, more just and more radically democratic social worlds for the twenty-first century, a search for self in troubling times. I hope to chart a course of action that acknowledges complicities with past atrocities, while outlining new myths that are more inclusive and not just “Indians first, and then us.”2

So I borrow my title from Schullery (1997). Like him, my version of “Searching for Yellowstone” is a search for self, for new self-understandings. And these understandings emerged out of an engagement with that symbolic space known as Yellowstone National Park. The congressional act of 1872 which established Yellowstone National Park reads, in part:

“This land is reserved

and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy or sale….

Dedicated and set apart

as a public park or pleasuring-ground

for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

(HAINES 1996A, 167)

I went there in 1988 as a tourist, and twenty years and fifty visits later I became convinced that a new cultural politics is being played out in the park and its surrounding communities.3 Indeed, the park is more than a pleasuring-ground. It is a magnet for national discourses and performances about Native Americans, history, gender, nation, and nature. In borrowing my title from Schullery, I am suggesting that this search extends beyond self—it speaks to the soul of a nation, and to the kind of nation we want America to be.

CONSTRUCTING THE TEXT AS “MYSTORY”

Guided by Gregory Ulmer’s concept of “mystory” (1989), I write from the scenes of memory, rearranging, suppressing, even inventing scenes, foregoing claims to exact truth or factual accuracy, searching instead for emotional truth, for deep meaning (see Stegner 1992, iv; Blew 1999, 7). Translating experience and memory into “fictional truth … is not a transcription at all, but a re-making” (Stegner, quoted in Benson 1996, 114). In so doing, I’m in the “boundaries of creative nonfiction [which] will always be as fluid as water” (Blew 1999, 7).

My texts travel among three levels of discourse: personal experience; popular ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Photo Montage 1: Mythic Native Americans and the New/Old West

- Photo Montage 2: Yellowstone Park and Lewis and Clark, Circa 2006

- Photo Montage 3: The New West, Memory, and the Author’s Family

- Notes

- References

- Index

- About the Author