![]() PART I

PART I

Renewing a Nation: The Zimbabwean Phoenix is Rising![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Phoenix Rising: Towards an Integral Green Zimbabwe

BY ELIZABETH SARUDZAI MAMUKWA

INTEGRAL GREEN ZIMBABWE – THE STORYLINE

While the Zimbabwean phoenix is in the ashes, the challenge for many a concerned citizen is, ‘How do we get it to rise?’ In this book our local and global Zimbabwean research community have shown that they are willing to do more than ask that question. They have gone further via ‘research and development’ thereby taking positive action, which contributes to getting the Zimbabwean eagle to fly. We shall reveal research work carried out by local PhD students, and Zimbabwean co-researchers from around the world, with the purpose of contributing in an integral way – as has been intimated in the Prologue – in turning the Zimbabwean society and economy around. Such work has been grounded in Schieffer and Lessem’s Integral Worlds model (2014). They depict the local–global realities of the South (Nature and Community), East (Culture and Spirituality), North (Science, Systems and Technology) and West (Enterprise and Economics), altogether serving to release our Zimbabwean genius, in a transformative rhythm. Here then, we share the passions of men and women who love their country and nation, and who are prepared to work in their various private and public, civic and environmental sectors to make a difference. We will see also towards the end of this book, these co-researchers deciding to stand up and come up with a sustainable, institutional solution in the form of a more coordinated approach to helping the phoenix to rise from the ashes. The opening lines in our journey of healing and restoration as a society and economy lie with the remarkable transformation achieved by the Chinyika community in rural Zimbabwe, from being on the verge of starvation, to gaining self-sufficiency. The closing lines of the penultimate chapter – duly interconnected with our opening – serve to reveal the phenomenon of Econet, Zimbabwe’s one and only multinational company, albeit representing itself in integral guise. The concluding chapter is not only a reflection on the Integral Green Zimbabwe journey as a whole, it will also illustrate a long-term solution to sustain and expand our efforts for the integral development of our country.

To be sure, African thinkers can also reflect on their traditional ‘religious beliefs and myths.’ But if African thinkers are really to engage actual problems, then it is clear that African philosophy has to – at some level or other – be connected with the contemporary struggles and concerns facing the continent and its diverse peoples. For it is not the ‘beliefs and myths’ of the peoples of Africa – in their intricate magnificence – that are mind boggling, but the concrete misery and political insanity of the contemporary African situation.

Serequeberhan (1991)

… we can easily admit that modern Africa will not really attain its cultural maturity as long as it does not elevate itself resolutely to a profound thinking of its essential problems, that is to say, to philosophical reflection.

Towa (in Serequeberhan, 1991)

1. Introduction: The Purpose of This Book

The purpose of this book is two-fold. The first objective is to share the developmental results of the work undertaken by our local and global research community, where the research has been carried out with (and not on) specific communities (Heron, 1996) to solve given societal problems. Such integral research was inspired by the economic and social ills that bedevilled Zimbabwe, particularly between 2004 and 2014. The question thereby addressed is, how may we respond as a country, as an industry, as communities, as organisations and as individuals to burning issues, which have resulted in a greater part of the population sinking into abject poverty? There are no jobs for the children to take up; the granaries do not have enough stocks to feed the people; while the majority of companies have closed, those factories and companies still limping along have lost critical skills; the family structure has been split, with one parent taking up a job in the Diaspora, to mention just a few of the challenges we have faced, and in many instances overcome.

In the different research projects highlighted here, the researcher became co-researcher as well as subject of the research. He or she would work together with other members of the research community to resolve the burning issues and challenges at hand. In all instances highlighted in this book, such integral research has not only materially benefited the given communities, but has empowered communities by catalysing peace and reconciliation as well as restoring confidence in the self, both at individual and at community level, from a perspective of building the capacity to resolve our own problems, through drawing on our unique gifts as Zimbabweans, as shall be seen below.

The second (and perhaps more important) reason for the book is to explore the options available to us as Zimbabweans to help the Zimbabwean Phoenix to rise from the ashes. The ultimate message that we seek to put across is that our fate as Zimbabweans is in our hands. We can be the authors of the remedies to heal our land and bring smiles to our people. We can bring back the days of plenty, using the basic gifts given to us by our creator, such as nature, spirituality, rhythm, Ubuntu/Unhu, and the spirit of pulling together as a people. The message is that we must go back to our traditional origins and revisit our age-old African values – ‘I am because we are.’ First we must re-establish our roots and identity, become comfortable in our own skin as Africans and as Zimbabweans. Once we remember who we really are in our indigenous context, in other words our Grounding (Lessem & Schieffer, 2010), we will realise that we have the power to make a difference. Our added strength will come from a combination of the indigenous and the exogenous, giving us the advantage of the best of both worlds.

To put this message across more effectively, we have enlisted the assistance of fellow Zimbabwean researchers and developers who have for years done some sterling work in the country and beyond – people who have already proven that it is very possible to come up with effective solutions to the woes of our land, because they have successfully done so. Included in this category are choreographer and academic Kariamu Welsh and agronomist and innovator Allan Savory, both based in the US as well as in Zimbabwe; Professor Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni based at UNISA in South Africa, co-founders of Trans4m, Professors Ronnie Lessem and Alexander Schieffer based in the UK and Geneva, and Zimbabwe-based citizen of the world, creative artist Cont Mhlanga. Furthermore, in my other chapter on the Calabash of Knowledge (Chapter 11), I draw strongly on the work of Mick Pearce, an internationally renowned Zimbabwean architect, who has become a friend and co-researcher in the course of our Integral Green Zimbabwean project.

In the Prologue of this book, Lessem and Schieffer, drawing on Integral Development: Realising the Transformative Potential of Individuals, Organizations and Society (2014), define ‘integral’ as the dynamic and inclusive incorporation of all the varied aspects of the human system – nature and community, culture and spirituality, science, systems, technology, enterprise and economics. They define ‘green’ as the prominence given to nature and its link with humanity in the development of a healthy ecosystem. For Lessem and Schieffer, an ‘Integral Green Society’ thereby embraces the environmental sector through nature and community; the civic sector through culture and spirituality; the public sector through science, systems and technology; and the private sector through enterprise and economics. At the same time, they see an Integral Green Economy integrally comprised of a community-based self-sufficient economy, a culture-based developmental economy, a knowledge-based social economy and a life-based living economy, altogether transcending both capitalism and communism. All this however hinges on a moral core of society, which is at the centre. As you go through the book you will probably agree with me that this moral core, for Zimbabwe, is our community-based value of Ubuntu/Unhu.

Zimbabwean historian and political scientist Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Chapter 2) throws a spanner in the works by highlighting the fact that Zimbabwe may be paralysed by ‘coloniality’, a phenomenon perpetuated through institutions and people that serve to reinforce the oppressive elements of colonisation long after African countries become independent states. The next question then is, is it possible for Zimbabweans to break the bonds of coloniality to allow Zimbabwean men and women to influence their fate? Another question is, how do Africans break the shackles of the North and West so that they have the freedom to come up with their own homegrown solutions? And yet another question; is it about breaking away from the North and West (and even the East)? The different contributions in this book indicate that it is possible to tame the forces of ‘coloniality’, and such a process of integral development, in our terms, need not be violent or loud. There are amazing men and women in Zimbabwe who are, in their own little or not so little ways (witness Chinyika and Econet for example), quietly and peacefully making a profound impact. Some of these men and women, through their communities and enterprises, have come up with local solutions with global relevance. Yet others have come up with solutions, which have faced global adaptation. It is our hope that, after reading this book, more people will realise that positive change is possible in Zimbabwe. It is happening. It depends on us, the Zimbabwean people.

In this opening chapter I will introduce you to the book, and to the different efforts that some people are making in our communities, and to the great potential that there is with regard to getting the Zimbabwean Phoenix to rise from the ashes.

2. The Structure of the Book

The book has been classified into six major sections, including Part I, which is intended to give a background to the context as well as to the book itself.

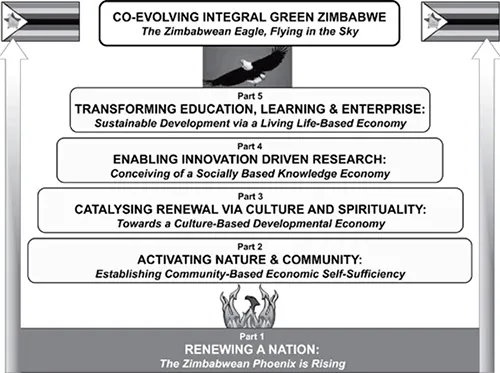

In Figure 1.1 we provide an overview of the six parts, presenting, altogether, the ‘integral rhythm’ to enable the Zimbabwean Phoenix to rise and to become, anew, a proud African eagle roaming the African skies.

Figure 1.1 The Integral Green Zimbabwe journey as mirrored in the structure of this book

You will notice that we employed the Integral Worlds framework to structure the book, enabling you to follow our journey to gradually building up towards an Integral Green Zimbabwe, literally from the ground (or ashes) up – beginning with nature and community.

All these parts are designed to highlight the different initiatives carried out by different people, communities and enterprises in their varied efforts to bring authentic indigenous–exogenous development to Zimbabwe. The intention is to keep together sections that speak to the same logic. The last chapter explores how we can create a vehicle for organising such initiatives to ensure a sustainable and developmental, institutionally-based continuation and sharing of such.

3. Part I: Renewing a Nation – The Zimbabwean Phoenix is Rising

Part I of the book attempts, not only to articulate what went wrong in Zimbabwe (why the Phoenix is in the ashes) through Ndlovu-Gatsheni’s scholarly research, but also what is being done, and what can be done in the future, to help the Phoenix rise from the ashes (Chapter 1).

In this section Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Chapter 2) embarks on a self-criticism drive (as an African and a Zimbabwean) where he first reflects on the issue of coloniality, where perhaps as Africans we continue to be our own colonisers. Well after independence, he contends, we continue to maintain the same institutions of colonisation in the same way our colonisers used such. He terms this ‘coloniality’, and suggests that for the Zimbabwean Phoenix to rise from the ashes, a process of ‘decoloniality’ needs to take place.

In this chapter Ndlovu-Gatsheni indeed challenges us as Africans to counter coloniality by influencing such institutions to rather develop knowledge for Africa as opposed to acting as care-takers to archaic colonial machinery. He further discusses the agony and violence in Africa, which he identifies as a struggle over limited resources. Integrally and developmentally then, one way of addressing this violence is to increase those capacities that it is in our power to increase, and seek to replace the ethos of ‘I conquer therefore I am’ with the Ubuntu/Unhu one of ‘I am because we are’. A living example of this is the Chinyika story where a starving area has been transformed into the land of plenty where more than 300,000 people, in the process of rediscovering who they are as Africans, are now as a result well fed and there is a robust food security strategy (Lessem, Muchineripi & Kada, 2012). In a way, the mere writing of this book is in itself a challenge to such coloniality, as we Zimbabweans have come up with workable local–global strategies of creating knowledge for Africa. Not only have they challenged the ‘coloniality of being’ by grounding themselves in their African-ness, but have attacked the ‘coloniality of knowledge’ by creating knowledge for Africa, as shall be seen in this book.

4. Part II: Activating Nature and Community – Establishing Community-Based Economic Self-Sufficiency

In Part II of the book, we focus on Self-Sufficiency, Community Building and Community Activation, which, for us, constitute the starting point for a healthy society and economy, in Zimbabwe if not in Africa as a whole. We dwell on the writings of Muchineripi and Kada, Kundishora and Mandevani (Chapters 3, 4 and 5, respectively) who in different (and yet very similar) ways transformed communities.

For Muchineripi (Chapter 3), also the founder of Business Training and Development (BTD) which hosts our doctoral programme, and Kada, the starting point was the trauma of colonisation, which had the effect of upsetting the African ecology when foreign methods of farming and foreign crops were introduced by the colonisers. The end result was that the people began to starve in Chinyika. The exogenous crops could not survive the droughts. Although Muchineripi made an attempt to feed the people, he soon realised that such a solution was not sustainable. However, while participating with Kada on a Masters in Social and Economic Transformation run by Trans4m in South Africa, he was spurred on to find a solution because of his renewed love of his people, of indigenous rapoko and the African Ubuntu/Unhu values (I am because we are). In the process of revisiting their agricultural history and roots, Muchineripi and Kada, with the wisdom and knowledge of Muchineripi’s mother, and a democratic process within the community, started to grow the traditional finger millet (rapoko), and the people’s stomachs and granaries started to fill up.

Now the miracle here is not necessarily the finger millet. It is rather that they went back to their indigenous roots for a sustainable solution to hunger and starvation. Even more amazing is the tripartite arrangement that was promoted through the community (Chinyika), government (the Ministry of Agriculture through its extension officers) and the private sector (Cairns Foods through Kada, its Human Resources Director at the time, as well as company agronomists). Muchineripi and Kada then activated all three sectors and also activated other rural communities as word of this wonderful work spread. This just shows what amazing things can happen if there is an integral ecological approach to addressing societal problems. More people have joined the Chinyika bandwagon, including inaugural Permanent Secretary for the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, Postal and Courier Services, Sam Kundishora, who introduced information and communication technology (ICT) to Chinyika farmers and secondary schools (Chapter 4). This has helped the people of Chinyika in identifying the appropriate crops, keeping an eye on the weather patterns and finding markets for their produce. As we shall see later, Kundishora has also combined forces, in Chinyika, with Econet. Together, they are spreading their ICT-based, agricultural wings around the country.

In the process of changing the face of Chinyika, traditional women were elevated to positions of leadership epitomised by the formidable, and at the same time humble, coordinator of the community council, Mai Mlambo. The women of Chinyika have, through the research and development spearheaded by Muchineripi, Kada and Kundishora, beautifully combined their new leadership role with their traditional roles of cooking and singing to make the work lighter. In the process of going back to their roots, the people of Chinyika also reverted back to the traditional technology of storing finger millet in sealed granaries, which has gone a long way in food security.

Whereas the Chinyika initiative was focused on healing the people through self-sufficiency, food security and the restoration of the adult position in the community where they are the repositories of solutions to community problems, community-based tourism (CBT) seeks to link Zimbabweans with their heritage and leverage such heritage for economic gain as well as to use such as a vehicle for passing on traditional knowledge from generation to generation. In a different way then, Mandevani activated and catalysed the community in rural Muda through culturally-based tourism, Kushanya Mumamisha (Chapter 5). He leveraged the Chaminuka Shrine, as indigenous spirit, and the Muda Pioneer Column Bridge, symbolising the exogenous historic invader, with a view to newly reconciling the two. Combining community and culture, economy and society, this project brought together three major stakeholders – Tour Africa Travel (TAT) (a family business), the Muda Community and the Government through the Ministry of Tourism.

For Mandevani, CBT served to catalyse ‘the process of reconnection’ with his African roots. Born and bred in Harare, he had drifted away from his African-ness, which has now been reawakened. He has therefore been ‘grounded’. CBT in this particular case then becomes a vehicle for reawakening the spirit of Chaminuka, which is the epitome of the Zimbabwean spirit. Such reawakening serves to build spiritual, economic and reconciliatory bridges. It becomes a vehicle of reconciliation between black and white (the white man forcibly took the land away from us) and between Ndebele and Shona (the Ndebele were responsible for Chaminuka’s death).

From an economic perspective, CBT serves to improve the lot of the stakeholders, in this case the Muda community, the Ministry of Tourism and TAT. This is a good example of Africans taking charge of their destiny. The proceeds of this tourism project will be split three ways among the three stakeholders. There is potential too to develop school leavers from the local schools into tour guides and other service providers, thereby creating much needed employment. There is also the potential to develop other national shrines along the same lines. Perhaps the biggest benefit is that the community begins to get in touch with its spirituality and to directly appreciate and benefit from its heritage. Because the Chaminuka Shrine is a sacre...