- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

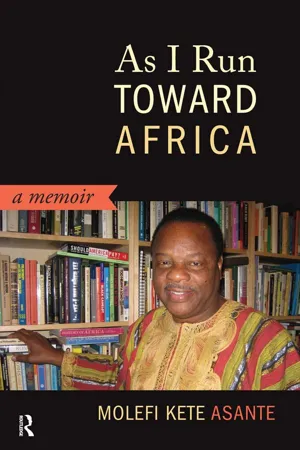

As I Run Toward Africa is Molefi Kete Asante's memoir of his extraordinary life. He takes the reader on a journey from the American South to the homes of kings in Africa. Born into a family of 16 children living in a two bedroom shack, Asante rose to become director of UCLA's Centre for Afro American Studies, editor of the Journal of Black Studies and university professor by the age of 30. The government of Ghana designated Asante as a traditional king in 1996. Asante recounts his meetings with personalities such as Wole Soyinka, Cornel West and others. This is an uplifting real-life story about hope and empowerment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access As I Run Toward Africa by Molefi Kete Asante in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

GEORGIA SWAMP LESSONS

I CAME OF AGE DURING A PERIOD of social unrest, when demonstrations against racial segregation abounded and protests were beginning to rise against the unrelenting political oppression of the American South’s black population. In my youth Black Studies was neither an idea for universities nor a destination for black students. The colors of my youth were red with the violence of physical abuse and black with the people who surrounded me in the coastal plains of South Georgia. Cruel history teachers who were often hidden behind hooded masks wrote the lessons I learned.

I am a child of the South, born during the Second Great European International War and reared in the heated environment of the turbulent age of social and political transformation. The revolutionary thinkers and actors of the 1960s who sought to create the discipline of Black Studies largely came from similar backgrounds or were inspired by the lay historians like J. A. Rogers, John Henrik Clarke, Yosef ben-Jochannon, Edward Robinson, and numerous others who were linked to that same America.

My story begins in a small-town family, a Georgia family, with its feet firmly planted in the realities of wars, both civil and uncivil, and reactions to racism. My own path from Georgia has led me to run toward Africa, both psychologically and physically, while retaining a strong and uncompromising attachment to my own experiences in the heroic struggles of African Americans.

I was born neither Molefi Kete Asante nor Nana Okru Asante Peasah; these are names I would later legally and traditionally acquire. I should have been given an African name at birth, and had my birth not come as it did after the history of black enslavement and racial segregation in America, I might have well started with an African name rather than an English one. Most African people in America have the names of slave owners: Washington, Williams, Lincoln, Gordon, Hunter, West, Connerly, Jeffries, Hilliard, Gates, Thomas, Sowell, Faison, Johnson, Jackson, Jefferson, and Smith are not African names; they are the names of our European oppressors. I hated these names. They meant nothing to my history but oppression, shame, domination, defeat, and depression.

“What’s your name, boy?” the man dressed in blue overalls asked. I was ten years old and didn’t like my birth name. “I am LeRoy, Larry LeRoy Smith,” I muttered. I tried to change my name by fiat, but it did not stick. No one ever called me LeRoy or Larry. Now I am happy that I was neither Larry nor LeRoy. I did not like those given names, but I disliked my surname most of all.

Carrying the surnames of those who enslaved your ancestors is a constant reminder of a lack of self-determination, a badge of conquest. I resented the emblem from the earliest moments I can remember—and told my parents so. I told them that I wanted a different name, a new name, a name that fitted me. They seemed to concur but did not have the foggiest idea of what they could do to get rid of those slave names. Neither of my parents completed high school or knew a black lawyer; they were victims who could not advance beyond what they knew. In their most reflective moments they always admitted, after some discussion, that they knew these English, Scottish, Irish, Dutch, and German names did not go with black people. It would take others like me to rebel and make the difference they wished they could have made.

These strange names for African people were indeed “slave names,” and wearing them without question was tantamount to accepting the enslavement and all of its violations of our Africanity—all of those traditions, motifs, habits, proverbs, artifacts, and nuances that make Africans different from Asians or Europeans. The baggage became heavier each time we were called by names that were not ours. Our own African ancestors’ names were unheard in some families for generations. I do not know how long our family went without any African names, though it might be said that we used nicknames to try to overcome our lack of authenticity. So I was “Buddy.”

Having an English name and not looking like an English person would plague me most of my early life, and it caused me to change my name. Even before I knew Africa in an authentic, historical sense, I would variously be LeRoy, Larry, and DuWayne—all names I naively believed were closer to Africa because few whites had those names. These names were not African, but African Americans certainly used them as alternative names during the 1940s and 1950s.

Yet even the names that I used for a week or a month did not satisfy me, and I would eventually have to abandon all relationship to English names. I knew that a correspondence between one’s name and one’s historical reality made it easier to maintain sanity. I desperately wanted to be sane, to be normal. And being normal meant having a name that made sense to me. Neither Arthur nor Smith made sense to me in the context of my African cultural legacies. Yes, it was true that I was born in America, but I felt no identification as an Englishman.

Mature people give themselves names from their history and culture; others are like pets that are given names by humans. A dog does not know that it is called “Rover”; as far as we know, it has no capacity to name itself. African Americans can name themselves.

I recalled that the Nation of Islam dealt with the issue of mismatched names by issuing its members the surname “X,” which stood for “unknown.” Of course, they have since allowed individuals to choose Islamic names, but this seems to be a re-enslavement of the African person. Why choose an Arabic name instead of an English one and think you have arrived at freedom? This was to become one of the biggest points of contention between myself and others who denied themselves and others the self-determination called for by Pan-Africanists. I never understood why Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar would leave English names for Arabic ones. There was a lack of historical consciousness somewhere in their decisions, but alas, for me, I had to run toward Africa itself.

Back then most African Americans never even considered the abnormality of having a European name—that was the norm—and yet it is like a Chinese person having a Jewish name or an Arab having a Swedish name. After many years it might seem normal, but it still would not match the history of your people.

Naming is a religious experience because it grants us access to the mysteries of creation. I knew this when I was very young, though I was ten before I first called myself anything other than the name my mother gave me or my earliest nickname. As I child I thought somehow that saying the word would make the reality: if you could say who you were, just call out the name, you could be that person. It would prove much more complicated than I knew.

“Buddy!” Whenever my mother called me by this name, I would run to her, answering, “Yes Ma’am.” It was the diminutive of my father’s Bud and my uncle Alfred’s DeBuddy. I never knew who generated the nicknames, but I suspected my grandfather Moses was the source. My mother seemed to take to Buddy rather easily and called me by that name more than my father did, who preferred the name I was given at birth.

Almost everyone on our street had a nickname, and it was almost expected that you would have one—as a sign of affection, a badge of how much people really paid attention to you. One of my brothers, Paul Calvin, was almost always called Red. I am not sure he felt he needed any other name. Another brother, the second oldest son, was given the name Eddie (who became Esakenti) but was called Sonny. On Oliver Street we had Dimp, Backyard Dog, Goose, and Turtle. We all accepted our nicknames and lived with them in perfect harmony—it seemed.

The naming phenomenon would sit at the door of all discourses in philosophy, black studies, and history for many years; it fueled cultural debates deep into the 1980s and 1990s and would still not be settled in the twentieth century, as attempts to relocate ourselves historically and culturally would occupy African Americans even more after the election of Barack Obama, a president with an authentic African name.

I trekked behind my uncle DeBuddy with my fishing pole, step almost for step, as we came in sight of the slowly moving water in the cypress swamp. In our family I was the male closest to my father’s youngest brother in age, so he took me under his wing. He was the first one to take me to the Okefenokee to show me the swamps with the ancient pregnant cypresses standing knee-deep in the water like platoons of John the Baptists ready to cry aloud—but they were silent. They were like sentinels over the mysteries of the watery maze, ready to initiate anyone who dared to enter this holy watery shrine to the alligators.

I learned to always stand back, waiting for a signal from my uncle to indicate when to go forward and when to step to the side, when to stop and fish, and when to move on. There was always respect, with nothing pretentious; everything was as the elders had dictated in their ordinary lives. I lived by the words of the adults. But I was not alone; we were quiet children then, listening and learning, waiting to speak when we had something to say and moving only when we were instructed to move. It was this ethic that often protected an entire population from wanton death. Watching was an act of survival. One never wanted to be out of line with this behavior because you would be severely corrected with, “Did I ask you to say something?” Of course, we learned to be keen observers, and this skill remained with me throughout my young adult life.

“Man, when we landed at Omaha Beach in October 1944, you were just two years old, but you were my brother’s son, my nephew, and I felt that we were fighting for you,” my uncle said to me. “Yeah, ol’ Pat-ton couldn’t move his army into Germany without the fighting Black Panthers.” He kept talking until he reached the bank of the large creek.

Uncle DeBuddy, a muscular man with the physical appearance of a world-class athlete, had managed to return to Valdosta after being a tank driver in the 761st Tank Battalion that fought its way from France through Germany and into Austria in search of Hitler. He was confident and strong; some would call him cocky, like some superior boxer or football player, because he knew that he had been a part of something great. He drove a tank through the Siegfried Line and helped get General Patton’s 4th Armored Division to Austria. Nothing in his clear, dark eyes spoke of the horrors he had seen when we sat at the water’s edge, holding our fishing rods.

DeBuddy, the most handsome of my grandfather’s sons, was proudly blue-black in complexion with the whitest teeth in a family of men with the whitest teeth. He always had a smile on his face, like he was eternally happy about meeting you, and yet there was something mysterious about him—not like the mystery that surrounded his father or his grandfather, but a priestly mystery related to his good looks. There was also a little conceit in him, the kind that comes with knowing that you look good and that others know it too. And to see him standing in our little house on Oliver Street, talking with my father or mother, was to see an African god commanding attention and casting his charismatic spell over the entire house from his kitchen pulpit.

He mesmerized me with his war stories. It seemed so incredible that my uncle had been to Europe, fought against Hitler’s armies, and returned to Valdosta. I respected him as I respected my parents, and I honored him as I honored them. As it was in the South among African people, my uncle was a second father to me.

Sitting with Uncle DeBuddy, I was in the presence of a history teacher, and I learned very early about perspective and agency—what you can see and what you can do—concepts that would later return to me as a mature adult. There was more to our discussion that day in the Okefenokee than roots or my birth. There was also something of blood and water as well as something literary and historical, though my uncle would not have called it that, and at the time I would not either. Today, upon reflection, I see more clearly how he opened me up to my journey toward Africa.

“I remember when you were born, boy, thirteen years ago,” Uncle DeBuddy said, with his baritone voice so low that I had to cock my head to one side to hear him. His broad, white smile registering light in his coal-black face, making his stories even more organic, natural, and effective. He was not the first of my grandfather Moses’s children to reach adulthood. My Aunt Jessie Mae, my father Arthur, and my uncle Moses Jr. were all older than uncle DeBuddy. However, he would be the first to die; yet his shadow, elongated to cover my early years, seems to have stretched over me like a protective blanket filled with comfortable memories and a guardian spirit.

DeBuddy, a war hero, who brought me so much myth, history, and mystery, gave me the multicolored dream of possibility when I was young. Not that the dream itself would have been any different had someone else given it to me, but as it stood, it was a dream richly drawn from the soil of one black family deep in the American South.

While we got ready to wade back toward the car, DeBuddy continued his stories. His rich, dark-chocolate complexion glowed in the Georgia sunlight as we walked through the muddy water, our boots up to our thighs. I kept thinking I saw alligators behind every fat-trunked cypress until he told me that what I was seeing were old rotten logs.

Sploshing through pond after pond along the swamp’s outer rim, with lilies scattered in every direction, we were two-for-the-world sportsmen, and we seemed to be a million miles away from America when I asked him reverently, “How did you feel—a black man fighting for America?”

“Fighting for you, boy,” he said, ending the question, I thought.

Treading more gently over the same terrain I asked, “Do they still have segregation in the army, being black and all that?” I guess I added the “all that” to include anything that I may have missed in my question.

“Not really.” His answer shocked me.

“What do you mean? Not really?”

“I mean the black soldiers preferred to fight alongside black soldiers; they trusted them. Didn’t trust no southern whites to look out for no black. Most of us fought in black companies.”

“But that’s segregation.”

“The world’s segregated, always will be. You just have to be better than anybody else and can’t take no offense to your person. Then you’ll always be free. Yeah, it was the time of segregation. The army was segregated. Truman would later try to integrate it, but for me and my company, we were happy to be with other black soldiers. The whites were too prejudiced.” Uncle DeBuddy stopped the trek back to the car just long enough to throw his line into the water one last time, and a large catfish wrestled with his fishing hook, creating a minor typhoon in the lily pond until he finally lifted it out of the water while I stood back, admiring his luck.

I often wonder whether my uncle was teaching me to love myself as a black person in a racist society or just expressing the conditions as he saw them. Either way, I admired him. My family would have a profound impact on my thinking, my ambition, and my commitment to African culture. It would not always be easy or comfortable, but enough influences would be there to give me the guidance that I needed.

“Work harder? Is that what you’re talking about when you say ‘be better than anyone else’?” I asked sheepishly.

“Just do what you do best, and do what you can do, and you’ll almost always outdo everybody else. Hell, I don’t know what you call it except doing the best you can.”

“You have to work together with all types of people, don’t you?”

“Oh yes, I’m not against working together with others—you should. You must do that, but you’ve got to find the leader that’s in you! If you don’t, you won’t be working with others; you’ll be working for them.”

“Everyone can’t be a leader, can they?” I asked, because I had heard somewhere that not everybody who wants to be a leader can be one.

“That’s a lie. Everyone’s got it in them. It just has to be found,” he said.

Puzzled and worried that I had stepped into a twisting perceptual machine much too advanced for my rather straightforward logic, I ventured, “You can’t really mean everyone can lead. Can you be serious, Uncle?”

“Naw, I didn’t say leadership ability. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not going to say everyone has leadership ability, but I know that everyone has a leader in them. I saw people in the army who had no leadership ability, if you mean skills for knowing how to inspire others, but they ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- 1 Georgia Swamp Lessons

- 2 Orientations

- 3 Passages

- 4 Destinations

- 5 Creations

- Epilogue

- Index

- About the Author