![]()

1 What is ‘Working scientifically’?

What is ‘Working scientifically’ and why bother teaching it?

It is true to say that investigative work has in the past not been given the same degree of emphasis as it currently has. The days of the occasional demonstration and the rigid, teacher-led practical activity seem to have gone. The fundamental shift of looking at the whole scientific process, its central role in developing theory and a justifiable emphasis on the ‘importance of science’ began when investigative science was developed as a curriculum area in the original National Curriculum for England in 1989 (I can remember this well as I was hastily given my first post of responsibility in my second year of teaching to deal with the seventeen attainment targets and ‘AT1’), but gathered further momentum in the 1999 review and change. With subsequent changes to the National Curriculum over the years, the terminologies have changed, the range of skills broadened, and as a result ‘Working scientifically’ has increasingly taken a central role within the curriculum until we have arrived at our current set of definitions and terminologies used in the National Curriculum.

Precisely because of the many changes over the years, developing an understanding of ‘Working scientifically’ can be problematic. The understanding of this term is dependent on who you ask, what stage they are at in their career, when a text you read was written, what and who you read and what version of the curriculum you are using. Therefore, you could well see the following phrases/terminologies that are sometimes used interchangeably:

Sc1

AT1

Inquiry skills

Enquiry Skills

Scientific enquiry

Investigative work

How science works

Scientific investigations

Working scientifically.

Generally, if you see:

SC1/AT1/ Scientific Enquiry: this relates to the curriculum pre-2000.

How science works: this relates to the curriculum post-2000, pre-2014.

Working scientifically: this relates to the curriculum post-2013.

Something to also be aware of is where a text has been written, as the terminologies might be slightly different. For example, in the UK, inquiry and enquiry are interchangeable yet in the US ‘inquiry’ is used. (However, it is becoming preferable to use inquiry to denote an investigation, and enquiry to denote a question.) It also depends on what scheme your school might have.

For clarity we will use the terminologies associated with the National Curriculum of England (framework document) September 2013, and subsequent updates, in this guide.

The National Curriculum in England: Science programmes of study (2015) states that:

Working scientifically specifies the understanding of the nature, processes and methods of science for each year group.

National Curriculum in England: Science programmes of study

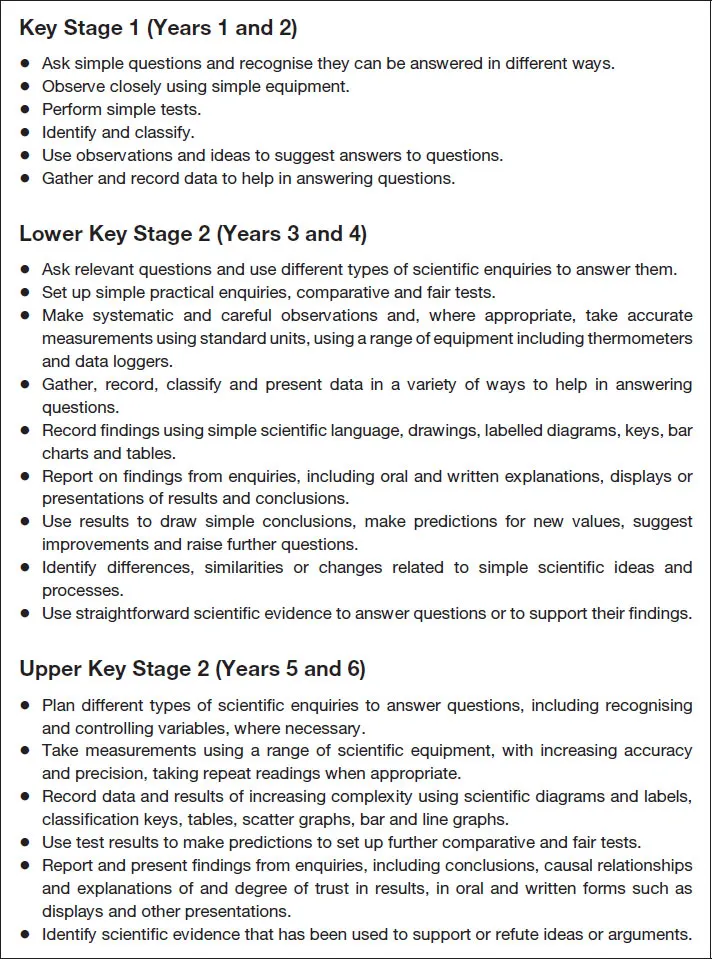

It then outlines the nature, processes and methods of science for each year (Figure 1.1). It further uses the phrase ‘scientific enquiry’ in its explanation and introduces the reader to a number of scientific enquiries which will be referred to later. It then details what should be taught (statutory) and gives some guidance (non-statutory). I would argue that to develop the teaching of ‘Working scientifically’ we need to do more than identify what skills it encompasses. We also need to tease apart those skills to gain an insight into what they might look like in the classroom to children and understand the steps in development of them all. Once we understand how each skill develops, we then need to recognise the practical activities, techniques and contexts that are effective for developing these skills, with the ultimate aim of helping children to becoming autonomous investigators.

Harlen and Qualter (2015: 98) help us by classifying the skills as:

• raising questions, predicting and planning (concerned with setting up investigations)

• gathering evidence by observing and using information sources (collecting data from investigations)

• analysing, interpreting and explaining evidence (making conclusions in investigations)

• communicating, arguing, reflecting and evaluating evidence (evaluating their investigations).

For some this is a very useful approach and in this guide I will use this as the basis for my chapters.

Figure 1.1 Working scientifically (taken from the National Curriculum in England: Science programmes of study, 2015).

Why bother teaching ‘Working scientifically’?

Apart from the obvious answer that it is fun and a part of a broad and balanced curriculum, first and foremost:

It can have a massive impact on progress, attainment and engagement in Science. As Ofsted note in their ‘Successful Science’ report (2011: 6):

In the schools which showed clear improvement in science subjects, key factors in promoting students’ engagement, learning and progress were more practical science lessons and the development of the skills of scientific enquiry.

It allows us to find out what the children’s ideas are. Quite simply, children’s ideas are important. Children’s ideas develop from interaction with their environment (I take environment to mean the physical world and the sum total of interactions in a child’s life). Much research has been done on this – you may have come across Piaget, Vygotsky, Bruner, Osborne and Freyberg in your studies. As Harlen and Qualter (2015) emphasise, we must use children’s ideas as the starting point in developing scientific ideas. However, children’s ideas that start in early childhood, borne out of experience of the world around them and how they interact with that world, are often in conflict with the scientific ideas contained in a formalised curriculum. These ‘alternative’ ideas or as some name them, ‘misconceptions’, can represent a huge barrier to progress, and unless they are thoroughly explored we cannot possibly hope to overcome them. Working scientifically allows us to see these ‘misconceptions’ and gives us the opportunity to correct them.

It is crucial to facilitate progress in conceptual understanding. The process skills contained in working scientifically and the scientific attitudes it develops are key to helping children make progress. Through exploration and investigation children can ask questions to test their ideas and seek answers to the questions they ask. For example, a child may be utterly convinced that all heavy objects sink. It is only when the child explores a number of objects and sees that some heavy objects do indeed float that this persistent idea can be explored and challenged and they can move past this to a greater understanding of the concepts contained in this (deceptively simple) phenomenon. The ideas that do not fit the evidence from the enquiry process usually are rejected and sometimes a fundamental shift or ‘penny drop moment’ can be achieved.

It helps maintain positive scientific attitudes. As reported in Ofsted’s ‘Maintaining Curiosity’ report (2013), scientific enquiry is crucial to developing and sustaining curiosity, and this, in turn, is an important factor in the development of the young scientist. Sadly, as the curriculum becomes more formal and content-driven, children lose some of the wonder, curiosity and excitement that science promotes. Keeping enquiry alive is crucial in maintaining these positive attitudes and will, in the long run, help you in your teaching. It can well promote science as a future career for children.

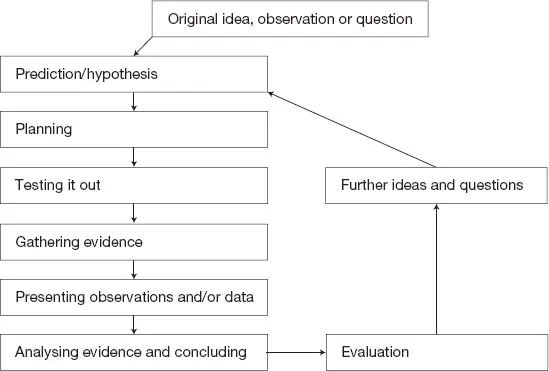

It models how scientists work. Working scientifically allows us to develop an understanding within children of how scientists work in the real world. The myth of the ever-wise male with a white coat, frizzy hair and goggles can be challenged and children can learn that anyone can be a scientist. As Driver et al. (1996) note, children have a fairly limited view of how science works and the nature of science; only when they are older do they develop the idea of testing ideas and seeking evidence. We can develop this idea a lot earlier by modelling the scientific method and developing an appreciation of the tenuous nature of scientific ideas and evidence. The initial stages of stimulating a child’s imagination and natural curiosity can lead to questions being asked and predictions and tentative hypotheses made. From there we can then encourage children to explore the range of ways of finding out answers to then testing their ideas, making observations and presenting what they find out. We can encourage reflection on the original question and make tentative conclusions that might need further testing, which can lead to a whole new prediction and investigation.

Figure 1.2 The scientific method.

From this process we can encourage a period of reflection and evaluation to see if what they have done was fit for purpose and actually could answer the question. This process is one that is performed every day by scientists in the real world and by providing exposure to this process we model the way that scientists work scientifically. This, in turn, can help throw light on an area that is full of misconceptions and stereotypes and thus promote positive scientific attitudes. We can only do this if we ‘work scientifically’.

How do we teach ‘Working scientifically’?

A rather glib answer to this question is ‘just do a practical activity’ and I cannot dispute the value of a well-placed practical activity. However, does this actually teach the skills? I do not think so. To teach the skills is an active process and requires an organised approach. This might be taken as me devaluing open-ended, child-led exploration, but this is not the case.

In the early stages of learning a skill, initial experience is vital. This comes from an early age (in the Early Years and Foundation Stage) through exploration of the world around them. Much of this is done unconsciously and one of the key features of learning the skills at this stage is observa...