eBook - ePub

The Cycladic and Aegean Islands in Prehistory

Ina Berg

This is a test

Share book

- 350 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Cycladic and Aegean Islands in Prehistory

Ina Berg

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This textbook offers an up-to-date academic synthesis of the Aegean islands from the earliest Palaeolithic period through to the demise of the Mycenaean civilization in the Late Bronze III period. The book integrates new findings and theoretical approaches whilst, at the same time, allowing readers to contextualize their understanding through engagement with bigger overarching issues and themes, often drawing explicitly on key theoretical concepts and debates. Structured according to chronological periods and with two dedicated chapters on Akrotiri and the debate around the volcanic eruption of Thera, this book is an essential companion for all those interested in the prehistory of the Cyclades and other Aegean islands.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Cycladic and Aegean Islands in Prehistory an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Cycladic and Aegean Islands in Prehistory by Ina Berg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Aegean Islands through time

Thanks to a long history of archaeological excavations and surveys, the Aegean islands have become one of the best explored regions in the Eastern Mediterranean. This was not always the case. In 1964, Vermeule’s book entitled Greece in the Bronze Age devoted less than 16 pages to the entire prehistory of the Aegean islands. It was Renfrew’s monograph The Emergence of Civilisation (1972) where the islands first took centre stage alongside the Greek mainland and Crete. In this seminal monograph, Renfrew offered the first systematic synthesis of archaeological evidence and developed models to explain the emergence of civilisation in the Aegean. Since then, a number of important publications have provided summaries of specific island regions and/or periods – most commonly focusing on the Cyclades. They include Barber’s extremely thorough, though now somewhat out of date, overview of prehistory in The Cyclades in the Bronze Age (1987). More recently, Broodbank’s An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades (2000a) has focused on the relationship between islanders and the sea, and has thus helped reshape our understanding of Early Bronze Age island communities. Review articles by Davis (1992; Davis et al. 2001) provide timely summaries of discoveries from all the Aegean islands. In addition, there are several German scholars who have written important syntheses on the Cyclades (Ekschmitt 1986; Rambach 2000; Alram-Stern 2004). Syntheses aside, scholars from a wide range of countries for example, Greece, UK, Italy, Germany, France and the USA, have worked tirelessly to publish their findings and analyses in books and articles. As a consequence of archaeological investigations and scholarly publications we not only have a much better understanding of artefact categories, individual sites, chronological synchronism and regional patterns, but researchers have also expanded our chronological range. When we previously thought that the first islanders arrived in the Neolithic, we now know that it was Palaeolithic and Mesolithic inhabitants that first called the islands their home. In writing this textbook, I have tried to incorporate insights from all the available literature. However, recognising that not all readers will have knowledge of multiple languages, I have prioritised articles and books published in English when providing references.

Pilgrims, travellers and tourists

When chatting with archaeologists working on Greek islands, there is little doubt that one of the attractions is the very fact that their chosen research area is an island space rather than a mainland location. However, this fascination many of us archaeologists feel about islands was not always shared and our current love for islands was preceded by indifference or even hostility as can be seen when we trace our engagement with the Aegean islands back through time from the modern world to the split of the Roman Empire.

As a consequence of the split of the Roman Empire, the rise of Christianity and the eventual religious schism in 1054 that divided Christendom into a Western Latin and an Eastern Orthodox half, Greece became an intellectual and political backwater. Knowledge of the Greek language, philosophy and classical culture practically died out in the West, as Latin learning and culture became the new foundations of society. Western familiarity with Greek geography also waned as biblical locations were given greater prominence on maps, and travellers from the West no longer visited Greece (Vin 1980). Instead, ecclesiastical and secular envoys, merchants and an ever-increasing number of pilgrims travelled through Greece on their way to the Holy Land during the Byzantine and Venetian eras (ca. 11th to 16th centuries). There were two dominant routes: a northern one through Thessaly and a southern one through the Aegean Sea. Of the two routes, the southern one was more popular and took travellers from Italy through the southern Aegean Sea with scheduled stops at Kythera, Crete and Rhodes (Eisner 1993; Vin 1980; Malamut 2004). Along this route, it is likely that pilgrims may have stopped at some of the other islands to supplement their water and food provisions. However, traces of these visits are scant in literary sources.

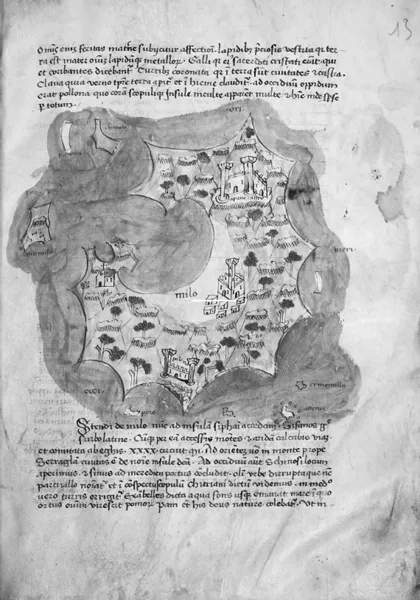

It is only towards the end of the 14th century (particularly through the influence of the Italian Renaissance), that Western scholars began to appreciate the cultural importance of Byzantine Greece again and developed an interest in the classical Greek past (Eisner 1993; Vin 1980: 131–161). Travel to Greece itself (with the aim of exploring and recording its antiquities) is first documented in the 15th century with the Commentarii by Cyriac of Ancona (Bodnar and Foss 2004) and the Liber Insularum Archipelagi by Cristofero Buondelmonti (1824 [1420]). Buondelmonti mentions 75 islands in total, although he did not actually visit all of them. He also prepared the first detailed maps of the region and individual islands (Figure 1.1), which he presented to Cardinal Orsini in 1420. In addition to providing the very first maps of the Aegean islands, Buondelmonti was also interested in the ancient archaeological statues and temples which he describes in detail and interprets according to ancient Greek mythology (1824 [1420]).

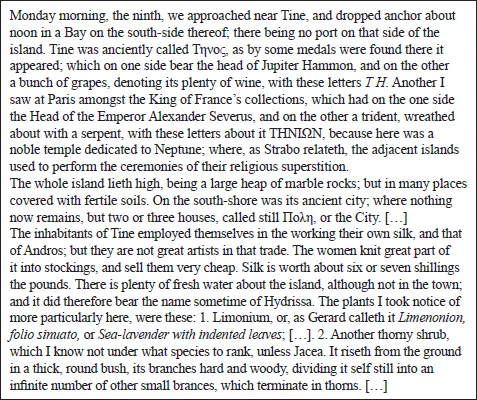

From the late 15th century AD onwards, the Aegean islands began to be conquered by the Ottomans. First were the northeast Aegean islands, then the Dodecanese and Cyclades with the last, Tinos, surrendering in 1715 (Davies and Davis 2007: Fig. 1.1). Initially, few of the islands were under direct Ottoman administration and most were controlled indirectly through intermediaries of the local Greek elites. Over time, however, all the islands became incorporated into the Ottoman administrative organisation. Because they were often ruled from a distance, the Cyclades suffered greatly from pirate attacks in addition to having to pay their annual taxes (Davies and Davis 2007; Slot 1982). Despite ongoing pilgrim traffic through the region, the Ottoman conquest and dangerous travel conditions made the islands unattractive to travellers, and the still tenuous links with the West were interrupted for over a century. From 1580 onwards, however, the Ottoman Empire granted more administrative, financial and religious liberties to the Cyclades (Slot 1982), and this provided the foundation for the slow resumption of travel to the islands. Travellers to the islands – among them De Thevenot (1686), Struys (1683), Wheler (1682), Spon (1724) and Randolph (1687) – wrote travelogues that reported observations on a wide range of subjects, such as geology, fauna, flora, agriculture, archaeology and local customs (Figure 1.2). Such reports were eagerly consumed by contemporaries living at home and unable to travel themselves (Augustinos 1994).

Figure 1.1 Cristoforo Buondelmonti, Liber Insularum Archipelagi (1420). The island of Melos, Greece (Wikimedia Commons, 2016).

In the 18th and 19th centuries, mounting interest in ancient texts and the discovery of archaeological remains resulted in a growing fascination by Western ‘gentlemen scholars’ with Greece, its inhabitants and heroic ancient roots (Eisner 1993: 71–82). It is the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann who best illustrates the desire to elevate the Greeks to an ideal. In his influential Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums he declared Classical Greek sculpture the pinnacle of artistic achievement, brought about by the superior humanity of the Greeks (1764). Embracing Greek heritage as the intellectual and cultural roots of Western civilisation resulted in increased travel by British, French and German writers and painters (Eisner 1993; Tsigakou 1991; Wills 2007). Initially a privilege of young male aristocrats, by the 18th century foreign travel had opened up also to the middle classes. Although Greece had never been part of the Grand Tour schedule, an ever-increasing number of travellers began to visit Athens and the Peloponnese to study the remains of an idealised ancient Greece. Most visitors restricted themselves to the Greek mainland; only those willing to forego some comforts in an effort to explore lesser-known regions ventured to the islands (Black 1985). Among these were Tournefort (1718), Riedesel (1774), Choiseul-Gouffier (1783) and Savari (1788). Similarly to writers of the 7th century, these travellers described and sketched ancient remains as diligently as they noted down observations about local dress, customs, religious rituals, and commented on climate, geography, agriculture and commerce.

Figure 1.2 Excerpt from George Wheler 1682. A Journey into Greece. Cademan: London, pp. 51–52.

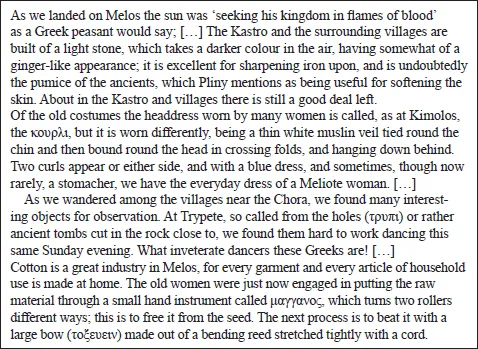

Closure of established travel routes and destinations during the Napoleonic Wars (1796–1815) increased the flow of travellers to Greece. Most of the visitors limited their exploration to mainland sites, but an increasing number began to visit the Aegean islands. These included Sonnini (1801), Chateaubriand (1814), Fiedler (1841), Murray (1845) and Bent (1885) who reported on local customs, interesting anecdotes, agriculture, industry, nature, history and archaeology (Figure 1.3).

The building of railways in France and Austria in the 1820s as well as Italy and Spain in the 1860s and the construction of a railway line and ‘motorway’ between northern Greece and Attica in Edwardian times made access to Greece much easier (Pemble 1987: 29–33). Nevertheless, travel to the Aegean islands remained challenging well into the 20th century as travellers had to overcome considerable hardship during their island journeys. Travel was physically demanding, living conditions basic, supplies difficult to replenish, illnesses frequent, pirate attacks possible, boats in a poor state of repair and heavy winds could enforce long waiting periods (e.g. Bent, M.V.A. 2006 [1885–1889]) (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3 Excerpt from Theodore Bent (2002) [1885]. The Cyclades or Life Among the Insular Greeks. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 29–38.

Figure 1.4 Excerpt from Bent, M.V.A. (2006) [1885–1889]. The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J. Theodore Bent. Greece and the Levantine Littoral. Vol. 1. Oxford: Archaeopress, p. 17.

At the same time, Greece took its first steps to becoming a destination for organised tourism. In 1833 it became included in package cruises to the eastern Mediterranean and tours by Thomas Cook and the HAPAG (Hamburg-Amerikanische-Paketfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft) package tours in 1891 (Brendon 1991; Kludas 2001). The first travel guidebook was published by the English publisher John Murray in 1845 (Figure 1.5); by 1900 the guidebook had been expanded to include route suggestions, coloured maps and a Greek-English vocabulary. Furthermore, the appointment of the Bavarian prince Otto in 1832 as the first king of the Greeks opened up Greece to German tourists (Eisner 1993: 126–128). Archaeological discoveries played a crucial part in uncovering ever more detail about the land that encapsulated the roots of Western civilisation. This heritage was the major attraction for travellers from northern Europe. This is beautifully encapsulated by the first motto of the National Greek Tourism Organisation, “You were born in Greece”. As excavations revealed ever more about the ancient past, the Greek mainland also became a desirable destination for study trips. In 1892, Dörpfeld, a German architect, organised the first guided culture tour to the islands during which more than 60 scholars and students of German, Russian, Italian, English, American and Greek nationality were introduced to their archaeology (Manatt 1914: 189).

It is only in the 1960s that the emphasis shifted from travellers interested in experiencing the ancient sites they had studied at home towards mass tourism with a predominant interest in beautiful scenery, relaxation and ‘getting away from it all’. In 1967, the Tourism Organisation of Greece recognised this change and altered their motto accordingly to “Having fun in Greece”, heralding major development in tourism which commenced in the mid-1970s. Between 1960 and 2002 the total number of tourist arrivals to Greece grew by an average of approximately 2.4% per year. In 1999, for example, tourism accounted for 6% of the Greek GDP and approximately 50–90% of the island/coastal regional gross product (Buhalis 1999). Following the onset of the worldwide economic crisis, Greece experienced a minor downturn (Dritsakis 2004). However, Greece has remained an incredibly popular holiday destination and was reported to expect record numbers of visitors in 2016.

Most of the visitors come from Europe, with Germany and the UK being the two largest contributors. Island and coastal areas are particularly geared towards tourism and have become ever more developed (Vlami 2010); Crete and Rhodes now receive almost 50% of all foreign tourists (Andriotis 2004; Coccossis and Constantoglou 2005). With unemployment in the insular regions below the national average and GNP higher than the Greek average, the most touristically developed islands now form the wealthiest region in Greece (Andriotis 2004). Unlike the medieval period, islands are no longer the backwater, but are decidedly in the centre of our appreciation and experience of Greece.

Figure 1.5 Front cover of John Murray (1884, 5th ed.) Handbook for Travellers in Greece, London: John Murray.

A brief history of archaeological explorations

The first serious archaeological investigation in the islands was undertaken by the French geologist Fouqué who had travelled to Thera in the 1860s to study the volcano (Tzachili 2006). The Suez Canal Company had recently begun mining for volcanic ash on Thera and the islet of Therasia, an essential ingredient needed for the high-quality cement used to construct the harbour and buildings at the newly established city of Port Said, Egypt. Thanks to this mining activity, the first prehistoric building remains were uncovered at Therasia, an islet off Thera, by a local doctor called Nomikos and the landowner Alafouzos. Recognising the importance of these finds, Fouqué expanded the excavations in 1867 and published them in his book Santorin et ses Éruptions (Fouqué 1879; translated by McBirney 1998: 96–104) (Figure 1.6). Small-scale excavations on Thera proper also revealed many discoveries, such as layers of pottery, two tombs, obsidian tools and gold rings near the village of Akrotiri (McBirney 1998: 104–107). We now know that, by following ravines and excavating where the ash layers were thinnest, Fouqué had accidentally discovered the famous Bronze Age town of Akrotiri. The French scholars Gorceix and Mamet continued Fouqué’s investigations and also opened up new locations in the Akrotiri area where they uncovered substantial building remains, pottery, small finds, animal bones and fresco remains (McBirney 1998: 107–123).

The Yorkshireman James Theodore Bent travelled extensively in the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa with his wife Mabel and published accounts of his journeys, including the well-known The Cyclades, or Life among the Insular Greeks (1885). Recognising that “in every island of the Aegaean [sic] Sea, […] are found abundant traces of a vast prehistoric empire” (Bent and Garson 1884: 42), Bent regularly published his findings in the Journal of Hellenic Studies. Among his contributions are his investigations into ancient mining on Siphnos, the excavation of tombs on Karpathos, excavations on Samos and an article on his excavation of two cemetery sites on Antiparos where he opened around 40 Early Bronze Age graves with accompanying marble figurines and bowls (Bent and Garson 1884).

Towards the turn of the 20th century, Christos Tsountas undertook investigations and excavations in the Cyclades with the aim of learning more about this under-explored region. Tsountas has been dubbed the ‘father of Greek prehistory’ for his wide-ranging contribution to illuminating, especially, the Mycenaean, Early Cycladic and Neolithic periods. On behalf of the Archaeological Society of Athens, he explored archaeological sites – particularly the more easily visible cemeteries – on Paros, Syros, Amorgos, Antiparos, Siphnos and Despotikon. Recognising the uniqueness of the finds and their geographic focus, he was the first to consider the Cyclades as a distinct cultural unit distinct from mainland Greece and other island groups. His two seminal articles (‘Kykladika’ and ‘Kykladika II’) in the Greek journal Archaiologiki Ephimeris from 1898 to 1899 thus form the foundation of much of our knowledge of the Bronze Age Cyclades (Fitton 1996: 106–107). Klon Stephanos, a physical anthropologist, continued Tsountas’ work in the first decade of the 20th century and excavated numerous cemeteries on Naxos, revealing hundreds of graves. The selection of the finds un...