- 159 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Essentials of Community-based Research

About this book

Community-based research (CBR) is the most commonly used method for serving community needs and effecting change through authentic, ethical, and meaningful social research. In this brief introduction to CBR, the real-world approach of noted experts Vera Caine and Judy Mill helps novice researchers understand the promise and perils of engaging in this research tradition. This book

• outlines the basic steps and issues in the CBR process—from collaboratively designing and conducting the research with community members to building community capacity;

• covers how to negotiate complicated questions of researcher control and ethics;

• includes a chapter written by community partners, among the examples from numerous projects from around the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Essentials of Community-based Research by Vera Caine,Judy Mill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Research in Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section I

History and Current Practice

1. What Is Community-based Research?

Community-based research has several historical roots and is often seen as grounded in post-positivism endeavors of research. Some value it for its recognition of local knowledge and experience, while for others it is research that compromises rigor in scientific processes. The debates are complex and often make visible the different theoretical and ideological positions of researchers, community members, and activists. Perhaps for most, community-based research is an approach to research that explicitly critiques the ontological and epistemological rigidity attributed to positivism while drawing on critical theory, feminism, anti-colonialism, and constructivism paradigms.

Community-based research comprises different things for different people. A number of disagreements in the field both propel it forward and at other times fragment the understanding and importance of the work. For some academics, community-based research is a connection between researchers and community organizations, while for community organizations, community-based research may be about conducting their own research with or without the support of academics (Trussler & Marchand, 2005). In this debate several issues become evident: first, community-based research must start with a clear definition; second, community-based research must build capacity to undertake research (by capacity building we mean that resources, infrastructure, skills, knowledge, and leadership are developed); and last, there is a need to engage in the process of community-based research authentically, ethically, and meaningfully.

Defining Community-based Research

The broadest definitions of community-based research include an understanding that the research is grounded in community, serves the interest of the community, and actively engages citizens. Community-based research is geared towards creating an environment for, or directly affecting, social change. We find the definition advocated by the Community Health Scholars Program of the WK Kellogg Foundation (Kellogg Foundation, 2015) useful. They define community-based participatory research as

[a] collaborative approach to research that equitably involves all partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings. [Community-based participatory research] begins with a research topic of importance to the community and has the aim of combining knowledge with action and achieving social change to improve health outcomes and eliminate health disparities.

Using this definition, it is apparent that community-based research is not a methodology or a set of methods that can be used, but rather an approach to research. This approach not only advances understanding or knowledge, but also aims to make a practical difference in the world (Flicker, 2008). It is inherently political, not only in its intention, but also in the process of democratizing the processes of knowledge production. Given its primary emphasis on community involvement in knowledge production and understanding of particular phenomena, it is necessary to be specific about who makes up the community.

Who Is the Community? What Is Participation?

The word community is often overused and evokes feelings of belonging without carefully considering and accounting for the diversity that exists within and among communities. The etymology of the word dates back to the late fourteenth century and stems from the Latin word communitas, which brings forward a sense of fellowship, courtesy, and the common and public. The origins of the word connect community to relationships with those who share feelings for each other, but community is also seen concretely as a body of people (Communitas, 2001-2005).

Drawing on this early understanding of what community means, it is important to see that community refers to more than a place or a geographical location, but that it also speaks to a sense of shared experience, relationships, and the reality that communities have a sense of organizing themselves. Drevdahl (2002) points out that “understanding the workings of power is integral to knowing community more fully” (p. 11). Recognizing these power dynamics within community is important, as these dynamics not only shape who participates in all phases of the research, but the ways in which the knowledge may be taken up later.

As we think carefully about community, we can see that in our own lives we belong to communities that are not homogenous, and that we are part of multiple communities simultaneously. While the etymology of the word community indicates a sense of commonality and shared space, there is also a sense of uncertainty, flexibility, and change present in communities. This more complex understanding of community calls forth that “[p]articipation in a community-based research project is a dynamic phenomenon that must be negotiated among an evolving web of roles and relationships” (Chung & Lounsbury, 2006, p. 2129).

Defining the evolving roles and relationships within each community-based research project is an ongoing process, shaped in part by understandings of the reason for the involvement of community as well as a continuum of understanding of what participation means. The involvement of the community is influenced frequently by the purpose and the scope of the research, but researchers using community-based research must also consider the contextual factors that are key in the implementation phase of the research. Given the intent of community-based research to create an environment where policies and practices can be changed, it is important to engage in discussion with communities about their involvement in the interpretation and application of the research findings or outcomes.

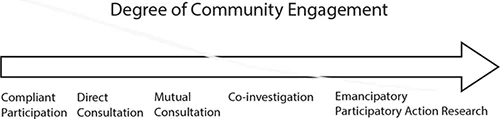

The level of involvement or participation of communities reflect a continuum. Loewenson, Laurell, Hogstedt, D’Ambruoso, and Shroff’s (2014) description of the continuum is shown here:

Across the continuum, and regardless of the level of involvement of the community, in each research project it is important to reflect core elements of community-based research, including mutual respect and trust, capacity building, empowerment, and accountability and ownership (Cargo & Mercer, 2008).

Historical Roots

Community-based research is grounded historically in the work on action research by Kurt Lewin in the 1940s, as well as the work of Paulo Freire, Orlando Fals Borda, and feminist and postcolonial scholars around the world. For Kurt Lewin (1946), a German-American social psychologist, action research was a means to overcome social inequalities; he was particularly interested in problem solving and change. Kurt Lewin saw the importance of building strong partnerships between academics and communities and advocated a utilitarian approach that valued agreement and consensus. While participatory approaches also are concerned with problem solving and strong partnership approaches, “participatory research recognizes the challenges inherent in doing work where the powerful in society may resist when they feel their power threatened” (Flicker, Savan, McGrath, Kolenda, & Mildenberger, 2008a, p. 241). Paulo Freire (1973, 1989) emphasized much more emancipatory approaches and recognized issues of power and conflict.

Much of Paulo Freire’s (1973, 1989) work was grounded in the strong belief that communities not only held knowledge, but that community members and organizations created knowledge. This shift in thinking validated the importance of experience and emphasized that scholarship could no longer be considered neutral. Freire’s thinking shaped community-based research in that it became clear that people must be actively involved in their learning and knowledge creation to address social justice concerns and to change their social-political conditions.

Encountering Scholars

Kurt Lewin (1890-1947) was a German-American social psychologist who made important contributions towards applied research, action research, and social processes. He is also considered a seminal theorist. His writing about action research is most important to community-based research. Toward the end of his life, he wrote about action research in relation to minority problems. For him, research leading to social action was critical and could be achieved through a series of steps that evolved much like a spiral (planning, action, fact-funding about the results/impact of the action).

Paulo Freire (1921-1997) was a Brazilian philosopher and an influential thinker on education. He contributed significantly to our understanding of critical pedagogy. His work focused on oppression and how education is linked to liberation and a sense of humanity. For Freire, education was a political act. He emphasized dialogue and the importance of working with people.

bell hooks (1952- ) is an American feminist and social activist. She is particularly interested in race and gender and how these produce and perpetuate systems of oppression. In her early work she noted a lack of diversity within the feminist development of theory; she advocated that women and others should take note of differences. She also is instrumental in defining the development of intersectionality, pointing out that gender, class, and race are connected. hooks argues that loving communities are critical to move beyond issues, while she also works to address significant power structures that are embedded in classrooms or educational settings.

This foundation is later built upon by bell hooks, who states that the learning process must be reciprocal and mutual; for example, in research, the inquirer is also impacted and transformed along with the participants because the inquirer also participates, bringing her or his own narratives and interpretations into the relationship and the work. (Hunter et al., 2011, p. 49)

A strong link can also be traced between community-based research and the adult education movement in which political empowerment is connected to literacy and skill development (Hall, 1981, 1988) and knowledge creation is seen as an ideological process. At the same time, research grounded in and responsive to communities emerged through the work of oppressed communities in South America, Asia, and Africa in the 1970s (Minkler, 2005). In particular, since the 1970s, community-based research has been further developed as a result of the insistence of Indigenous peoples and organizations that represent them (Fletcher, 2003). The involvement of Indigenous peoples also brought with it a strong focus on the right to self-determination. As Cargo and Mercer (2008) have pointed out, self-determination has “emerged parallel to the sovereignty movements of indigenous people and the desire for other marginalized and underserved populations (e.g., HIV/AIDS and disability movements) to assert control over the research and programs that affect them” (p. 330).

As researchers and communities began to realize the potential inherent in community-based research to democratize knowledge, validate multiple sources of knowledge, and achieve change and self-determination, the demand for community-based research increased. During this time, through the popular education movement, research expanded to include/embrace/incorporate a focus on social and environmental justice, and to ensure that knowledge was translated into action. Marxist, queer, and feminist researchers further contributed to the development of community-based research, particularly by arguing for greater decision-making power over studies that took place within their communities.

Ontological and Epistemological Underpinnings

The historical foundations of community-based research already point to different ways of understanding not only how we know (epistemology), but also to how we might understand the nature and relation of being (ontology). Different ontological and epistemological understandings in turn also shape what tools researchers use and which methodologies are most appropriate. It is important to understand that community-based research is an approach to research and reflects both ontological and epistemological positions that are grounded in its historical development, but that diverse methodological choices (such as qualitative and quantitative designs) are possible within this approach.

Community-based research most often draws on constructivist and critical theoretical perspectives, as knowledge is socially created. Ultimately, community-based research “recognizes local knowledge systems as valid on their own epistemological foundations and views them as contributing to a larger understanding of the world and place of humans in it. It takes as an a priori assumption that research and science are not value free” (Fletcher, 2003, p. 32). Knowledge creation is transactional and interactive, reflecting participatory ways of being. Researchers and community members engage ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Section I: History and Current Practice

- Section II: The Practice of Community-based Research

- Section III: Contexts and Challenges

- Section IV: Future Challenges

- Appendix: Resources on Community-based Research

- Notes

- References

- Index

- About the Author