![]()

PART 1

Context for Innovation and Improvement

Chapter 1 Synopsis – Patient Safety: A Brief but Spirited History

The authors provide a review of the evolution of the patient safety movement through three primary periods of development. The chapter challenges readers to think about how the movement lagged despite evidence of medical error and how it has subsequently grown into an influential movement. The narrative highlights evidence, information and knowledge evidence, information and knowledge (EI&K) episodes that contributed to this evolution.

Chapter 2 Synopsis – Concepts, Context, Communication: Who’s on First?

Conceptual murkiness has the potential to compromise patient safety efforts. In an effort to reduce that potential, the authors highlight differences between key terms that must be understood across professional groups, task teams and organizational levels in order to support reliable EI&K processes. They argue a consistent terminology and a shared understanding of its use is critical for establishing a solid EI&K sharing process for patient safety.

Chapter 3 Synopsis – Potential for Harm Due to Failures in the EI&K Process

This chapter discusses the need to improve EI&K identification, acquisition and transfer. The argument is made through a discussion of an accidental death in which failures in evidence identification during a clinical trial was identified as a contributing factor. The authors advocate for an exploration into EI&K seeking and sharing behaviors as an element of safe care from the systems safety perspective. This approach is an innovation for EI&K service design yet to be capitalized on in patient safety circles.

![]()

1

Patient Safety: A Brief but Spirited History

Robert L. Wears, Kathleen M. Sutcliffe and Eric Van Rite

Experience is by industry achieved and perfected by the swift course of time.

The Emergence of a Field of Focus

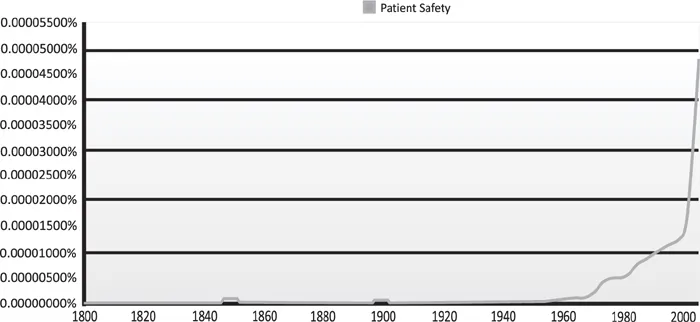

Conventional wisdom regards the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) To Err is Human (Kohn, Corrigan and Donaldson 2000) as the watershed moment for the field of patient safety – when harm from medical care was suddenly recognized as a large-scale problem and patient safety was propelled to the top of the national healthcare reform agenda. Indeed, as Figure 1.1 shows, since 2000 there has been a dramatic increase in attention paid to patient safety.

Yet, this pattern of attention is not evidence that To Err Is Human marked the start of patient safety reform. The report itself rests upon a series of other historical episodes, as shown in the timeline in Appendix 1.1. These episodes contributed basic information, and also fueled the social processes through which that information was: validated and accepted as evidence; interpreted and given a moral dimension; and, ultimately transformed into taken-for-granted knowledge (Latour 1987) that was used to justify reform (Hilgartner and Bosk 1988).

Figure 1.1 Relative Frequency of the Phrase “Patient Safety” in English Language Books Over Time: 1800–2008

Source: Google, 2013. Ngram Viewer. Available at: http://books.google.com/ngrams [accessed: 1 April 2013].

This chapter traces the historical development of patient safety as it evolved from a set of sporadic concerns to a sustained social movement. Three periods are examined:

1. The sporadic period, where isolated evidence appeared but did not coalesce into a coherent body of thought.

2. The cult period, characterized by the development of a small group of vocal and passionate believers.

3. The breakout period, in which patient safety became established as a legitimate area of activity and enquiry in healthcare at large and in the broader society.

The goal is to examine a few illustrative episodes in each period, but not to comprehensively discuss every element on the timeline; in addition, events in the past five years are not covered in great detail, as it is not currently knowable which are truly influential and which are merely passing. More detailed and comprehensive histories are available (for example in Sharpe and Faden 1998 and Vincent 2010). The chapter concludes by addressing two additional questions: Why did patient safety emerge as an organized social movement in the 1990s when fundamental evidence about hazards in healthcare had been known and discussed for at least the previous 150 years? And, once the patient safety movement emerged, what explains its subsequent continuation and evolution?

Three Periods of Patient Safety History

PERIOD ONE: THE SPORADIC ERA

The sporadic period, which ranges from ancient Greeks to about the 1950s, is characterized by intermittent insights into the hazards of healthcare, some of which have endured in specific practices. Yet, for the most part they were “one-off” processes, which were not mutually informative and did not result in a comprehensive or sustained sphere of activity. Figure 1.1 illustrates the sporadic nature of this period by showing appearances of the term “patient safety” in English language books; note prior to about 1950 there are long periods where the phrase never appears.

The famous dictum “First, do no harm” is commonly attributed to Hippocrates, but does not appear verbatim in his writings. Still, Hippocrates advises physicians to “abstain from harming or wronging any man” (Vincent 2010: 3), indicating that concern for the safety of medical care dates to classical times. Doubts about the safety of medical practices continued to be expressed, albeit occasionally, as medicine came of age in the modern era. A medical student graduating in 1835 noted “… that medicine was not an exact science, that it was wholly empirical and that it would be better to trust entirely to nature than to the hazardous skill of the doctors” (Sharpe and Faden 1998: 8). Similarly, Florence Nightingale in 1863 wrote, “the very first requirement of a hospital [is] that it should do the sick no harm” (Sharpe and Faden 1998: 157).

In 1847 Semelweiss provided the earliest organized, empirical evidence about the risks of healthcare. He based his insights into the origin and prevention of puerperal sepsis on empirical observations. Similar to present day healthcare researchers, Semelweiss was motivated by a personal situation – the rapid death of a beloved colleague who had cut his finger during an autopsy (Vincent 2010). This prefigures the prominent role that dramatic, morally imbued narratives will play later in the evolution of patient safety.

4 BCE: Hippocrates writes “abstain from harming or wronging any man.”

1847: Semmelweis documents the risks of medical treatment.

1860: Nightingale states “A hospital should do the sick no harm.”

1915: Codman designs classification of reporting of surgical errors.

In the early twentieth century, Ernest Amory Codman, a surgeon inspired by Taylor’s “scientific management” theories, argued for routine recording and scientific assessment of surgical outcomes and for making results publicly available (Timmermans and Berg 2003). He developed a seven-category causal classification scheme to categorize unsuccessful cases. Four were labeled “errors” (of skill, judgment, equipment, diagnosis), and a fifth “calamities of surgery” over which there were no control. Codman’s efforts were partially adopted by professional organizations and also became part of the hospital standardization movement in the US, playing an important role in the development of an accreditation system that ultimately became The Joint Commission (Timmermans and Berg 2003: 9).

PERIOD TWO: THE CULT ERA

The modern patient safety movement took shape as bits of data and evidence began to coalesce into a more related whole, and through the formation of a self-selected group that was interested in advocating for safety in healthcare. This small group of passionate believers was little known outside of their own circles.

Evidence, information and knowledge in this period came from a variety of sources. Some sources were scientific in nature and some were based in narrative; some rested in healthcare and some were taken from the social and safety sciences.

1959: Moser’s book Diseases of Medical Progress.

1978: Cooper: Preventable Anesthesia Mishaps published.

1982: 20/20 “The Deep Sleep” airs.

1984: Libby Zion dies.

1985: Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation formed.

1991: Harvard Medical practice studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

1994: Leape: “Error in Medicine” in the Journal of the American Medical Association published.

1995: Boston Globe Columnist Betsy Lehman dies.

1996: First Annenberg Patient Safety Conference held.

1997: National Patient Safety Foundation formed.

Evidence Raises Awareness

Developments in healthcare began with physician David Barr’s 1955 Billings Memorial Lecture entitled “The Hazards of Modern Diagnosis and Therapy – The Price We Pay” (Barr 1955) in which he identified risks posed by medical care, and argued that this was an inevitable (and mostly worthwhile) price to pay for therapeutic advances. Nonetheless, he concluded that physicians had a responsibility to avoid incurring unnecessary harm to minimize the price that physicians and patients both pay for modern disease management (Barr 1955).

By 1959, the ground had shifted a bit; military internist and educator Robert H. Moser’s book, Diseases of Medical Progress, promoted the perspective that harm was not an entirely unavoidable byproduct of medical success but also a consequence of unsound practice without due regard for the balance of risk and benefit (Moser 1959). In the ten years between editions, the text increased in size eight-fold (Moser 1969).

Gastroenterologist Elihu Schimmel expanded this line of thinking by focusing on episodes of harm (but excluding potentially harmful situations) in his 1964 paper on the hazards of hospitalization (Schimmel 1964). Schimmel reported that 20 percent of hospitalized patients suffered one or more adverse events, and 1.6 percent died as a result. However, he also noted that modern medicine cannot always be used harmlessly, and worried that a focus entirely on safety would produce a therapeutic nihilism: “… the dangers of new measures must be accepted and are generally warranted by their benefits” (Schimmel 2003, reprint of 1964 article: 63).

Geriatrician Knight Steel and his colleagues replicated Schimmel’s work in showing roughly similar results: 36 percent of patients suffered some sort of adverse event; 9 percent were major and 2 percent fatal (Steel et al. 1981). Steel’s research team did not try to assess preventability, or balance risk and benefit, but concluded that technical, educational and administrative means should be sought to reduce the number and severity of adverse events caused by care.

Periodic crises in the availability and affordability of malpractice insurance, starting in the 1970s and continuing to the present, led to studies of medical harm to inform the development of alternative compensation systems. The Medical Insurance Feasibility Study was the first to establish a statewide (California) estimate of the burden of medical harm (Mills 1978; Mills, Boyden and Rubamen 1977). It was followed about a decade later by the Harvard Medical Practice Study, which used a roughly similar methodology to estimate harm in New York hospitals and obtained similar results. From a review of 1984 medical records, the study found that 2,550 patients were permanently disabled and over 13,000 died from causes related to adverse care events (see Brennan et al. 1991; Leape et al. 1991 and Localio et al. 1991). In these studies, approximately 4 percent of hospitalizations showed evidence of injuries from care, and about 1 percent of hospitalizations were attributed to negligence.

The 1991 Harvard study received brief national publicity and was more influential than earlier studies for several reasons (Van Rite 2011). First, the authors extrapolated the results to the entire state of New York, giving a specific number of deaths, which was more dramatic and impactful than a rate. The authors also drew different conclusions from roughly the same empirical results. They implied that adverse events were not a reasonable price to pay for medical progress, but rather argued that the burden of iatrogenic injury was “large” and “disturbing.” Finally, the authors differentiated negligence from error or safety; this justified targeting medical error as a legitimate field for research and policy, independent of – and perhaps even more important than – negligence and malpractice (Van Rite 2011).

PERIOD THREE: BREAKOUT ERA

As patient safety moved into the larger public sphere, it faced a bit of opposition and denial; but that was quickly replaced by a scramble by the healthcare industry to say, in effect, “We’re on it.” Three episodes (among many) stand out as highly influential in bringing about this change:

1. Publication of To Err is Human;

2. The British Medical Journal special issue on safety; and

3. The National Health Service (NHS) report, An Organisation with a Memory, which appeared within a few months of each other (Department of Health 2000; Kohn et al. 2000; and British Medical Journal issue on patient safety, 18 March 2000).

These publications were influential not because they contained new information, but because of the venues in which the information appeared, and the legitimacy granted by such appearance. That is, these publications were not causal influences by themselves, but instead were the effects of previous causes (such as those described in this chapter). Each publication amplified what had been previously known, brought it to a much larger audience, and gave it an imprimatur with greater credibility and legitimacy that derived from the distinction and reputation of the publishers.

“After these reports, no government or care delivery organization could ignore patient safety.”

The 2000 IOM report To Err is Human received massive publicity that surprised even its authors. The report was a rhetorical triumph; it combined the estimate of 44–98,000 US deaths from previous studies with the personal stories of Betsy Lehman (discussed elsewhere in this text), medication misadministration casualty 8-year-old Ben Kolb, wrong site surgery victim Willie King, and others. The principal aim of the report, which was based on more than just the Harvard study, was to establish patient safety as a major required activity of modern healthcare (Kohn et al. 2000). It concluded with a call for a national effort, including establishing a “Center for Patient Safety” within the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR; now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, AHRQ). Curiously, there seems to have been little or no discussion of the appropriate home for the government’s safety research portfolio. President Clinton promptly ordered a government-wide study on the feasibility of the recommendations. A series of hearing and public meetings with stakeholders followed, from which AHCPR/AHRQ eventually developed a safety research program (Quality Interagency Coordination; QuIC Task Force 2000).

The March 18, 2000 issue of BMJ, the British Medical Journal, was a special issue, “Reducing error, improving safety,” edited by US-based patient safety visionaries Lucian Leape MD and Donald Berwick MD, and included a dramatic cover of a plane crash. It is interesting to note that in their opening editorial, Leape and Berwick cite information as critical: “…the safety of our patients and the satisfaction of our workers require an open and non-punitive environment where information is freely shared and responsibility broadly accepted” (Leape and Berwick 2000: 726).

2000: Institute of Medicine publishes To Err Is Human.

2000: The British Medical Journal publishes a Special Issue on Patient Safety, Leape, Berwick editors.

2000: The British National Health Service publishes An Organisation with a Memory.

2001: Josie King dies at Johns Hopkins.

2004: World Alliance for Patient Safety is formed by the World Health Organization.

In the Unit...