![]() PART I

PART I

Pharmaceutical Knowledge Management![]()

Chapter 1

Setting the Parameters

Introduction

Knowledge Management (KM) is notoriously difficult to define and indeed represents different things to different people. There is no set formula: every company has its own structure, environment, culture and goals, all of which have a critical effect on KM. Every approach and application is unique: there is definitely no ‘one size fits all’. This is perhaps why the concept has struggled for wider recognition: it is open to interpretation, represents different things to different people and requires a deep understanding (along with some passion!) for it to be successfully initiated and embedded within an organisation.

In this opening chapter, we provide a comprehensive coverage of the discipline for those who are relatively new to it. We begin with a brief look at the origins of KM, discuss some principles and definitions, and why we should be doing it at all. We also introduce our KM Framework to help pull all of this together, and provide a selection of Good Practices along with some of our insights and further references for those who would like to find out more.

An Introduction to Knowledge Management

THE ROOTS AND DEVELOPMENT OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

The social practice of Knowledge Transfer has been around since cavemen started hunting in groups and painting their experience on cave walls. Knowledge Management as a business practice has been developing since the 1990s. Koenig (What is KM? Knowledge Management Explained May 2012) attributes the birth of KM to the use of intranets in large global consultancies, where people recognised that if they shared their knowledge about their clients and about how they went about their work they could avoid reinventing the wheel, underbid their competitors, and make more profit. They then realised that they also had a product in Knowledge Management.

One can argue that the key principles of Knowledge Management were established in the 1990s, and that in the ‘Noughties’ KM has developed through:

• new computer-based technologies;

• a deeper exploration of methodologies and approaches by established experts and practitioners;

• the education and up-skilling of new practitioners;

• absorption into, or combination with other business management disciplines such as information and library management, records management, Data Management, organisational learning, business and process improvement, and so on.

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT?

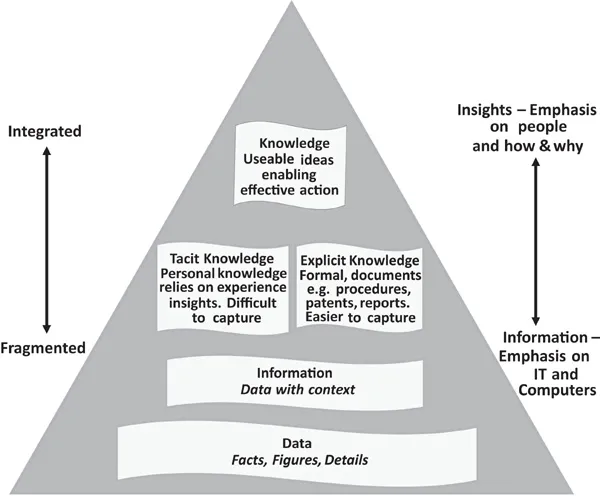

Some regard it as ‘old hat’ but we believe it is useful to describe data, information and knowledge as a hierarchy.

Figure 1.1 Knowledge, information and data

Some also add a further layer, wisdom, to cover the choices and judgments that people make with their new knowledge, but we will contain our description to the three layers. It helps to explain the hierarchy by using the analogy of a train journey:

• data: departure and arrival times as given in the timetable;

• information: the additional content that enhances the data such as whether the train has first class carriages and a buffet car;

• explicit knowledge: it may be that the train is delayed by x minutes, or that only the front carriages will stop at a particular station. This will be provided on the display board at the station, or announced over the public address system;

• tacit knowledge: where regular travelers on this train stand on the platform to access the doors. A fellow passenger tells you that this train is always ten minutes late!

Here are a few definitions to help create a more detailed representation of Knowledge Management. We begin with Duhon’s from the relatively early days of KM:

Knowledge Management is a discipline that promotes an integrated approach to identifying, capturing, evaluating, retrieving, and sharing all of an enterprise’s information assets. These assets may include databases, documents, policies, procedures, and previously un-captured expertise and experience in individual workers. (Duhon 1998)

The first part of Duhon’s definition has a clear connection with the cycle of knowledge that we favour and describe below, but it stops short of mentioning knowledge sharing and does not cover how the ‘information assets’ must be used to justify the whole process and to gain value and benefit.

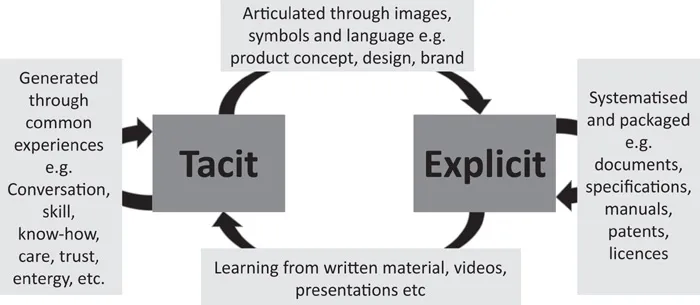

The second part of Duhon’s definition leads us into the area of explicit and tacit knowledge. Not everyone buys into the use of these terms:

Nonaka and Takeuchi’s linguistic confusion that led to the false dichotomy of tacit and explicit knowledge. (Newman 2002)

However, we believe that they help to provide a context for applying Knowledge Management tools and techniques and are implicit in an understanding of KM itself. Defining explicit and tacit knowledge helps us to think more clearly about the processes that we apply to knowledge in order to derive benefit:

• Explicit knowledge is what is written or recorded in documents, databases, websites and so on. It is very tangible and can be easily stored, accessed, worked on, and transmitted or distributed.

• Tacit knowledge is the knowledge that is in our heads such as know-how, experience, insights, ideas and intuition. It is usually richer knowledge but can be difficult to define and access. It requires the right environment, culture and questioning techniques to unlock and share it.

The flow between tacit and explicit knowledge is as follows (Figure 1.2):

Figure 1.2 Tacit and explicit knowledge

This dynamic between tacit and explicit knowledge is also intrinsic to the Knowledge Transfer processes that we describe later in this chapter.

If we fast forward to close to the present day, Snowden’s definition is an example of how the thinking about Knowledge Management has shifted:

The purpose of Knowledge Management is to provide support for improved decision making and innovation throughout the organization. This is achieved through the effective management of human intuition and experience augmented by the provision of information, processes and technology together with training and mentoring programmes.

The following guiding principles will be applied:

• all projects will be clearly linked to operational and strategic goals

• as far as possible the approach adopted will be to stimulate local activity rather than impose central solutions

• co-ordination and distribution of learning will focus on allowing adaptation of good practice to the local context

• management of the KM function will be based on a small centralized core, with a wider distributed network. (Snowden 2009)

There is much more of an emphasis here on tacit knowledge, on the practical application or outcomes of KM, the importance of relating it to business goals, and the desire to make it as decentralised and so embedded into day-to-day work as possible. It makes a shift from the process and means to the outcomes achieved by KM. We believe that this is the fundamental place to focus on as we shall discuss later.

The last definition is Gurteen’s, and although ten years older than Snowden’s, it is the one that’s very close to our own current vision of KM:

Knowledge Management is a business philosophy. It is an emerging set of principles, processes, organisational structures, and technology applications that help people share and leverage their knowledge to meet their business objectives. (Gurteen 1999)

Gurteen refers to Knowledge Management both as a philosophy for business (a way of thinking) and a means to achieving business objectives (the processes). His definition also neatly links together the triangle of people, processes and technology which are critical to KM, and which we reflect in our knowledge framework below. The only difference from the present is that the principles are no longer emerging but are very much established.

A Framework for Knowledge Management

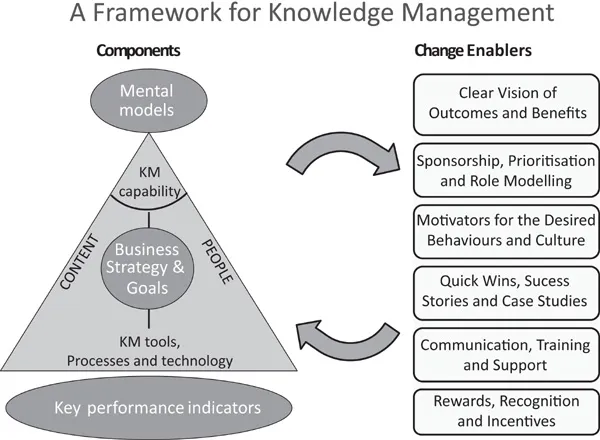

There are many aspects to Knowledge Management, and our framework attempts to pull these together in order to provide a ‘helicopter view’ or reference model for this book.

Figure 1.3 A framework for Knowledge Management

The left hand side of the framework consists of what we believe are the core components of Knowledge Management: the mental models that provide the common language around KM in the organisation, the business goals that provide the context for KM activities, and the measures (or Key Performance Indicators – KPIs) that determine their success, the sources of knowledge (Content Management and people), and the tools, processes, technology and capabilities that facilitate their flow.

The right hand side of the framework consists of the change enablers. As the name implies they are the key to influencing mindsets, values, behaviours and ways of working within the organisation. They help people to ‘really get it’. This shift can be driven by a belief that Knowledge Management is ‘the right thing to do’. But a more sustainable driver is the role modelling by managers and executives who themselves ‘get it’.

This chapter focuses on the components of our Knowledge Management Framework (KM Framework), the left hand side. We come back to the change enablers in Chapter 7 where we explore strategies for driving and sustaining KM in the Pharmaceutical Industry, and our interviewees’ experience of putting them into practice.

Mental models, a tie in to the organisation’s strategy and goals, and KPIs provide the ‘scaffolding’ for our KM Framework, so we begin with these three.

MENTAL MODELS

Mental models provide people with a way of thinking about Knowledge Management: the common language that can be used within an organisation. There are two such models that are at the heart of KM: the ‘Knowledge Cycle’, and ‘Learning Before, During and After’.

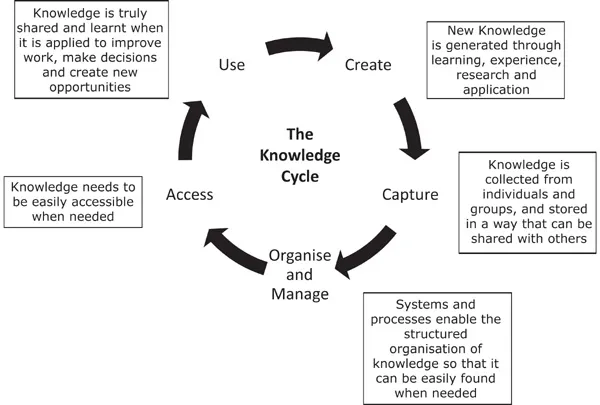

THE KNOWLEDGE CYCLE

The Knowledge Cycle is a representation of the various stages of knowledge development and use.

Figure 1.4 The Knowledge Cycle

This model is circular: the usual starting point is the creation of knowledge and its application to an activity that will in turn create new knowledge.

It is easy to apply the model to explicit knowledge, but it also works for tacit knowledge if we think of the brain as the central organising and managing function rather than some form of database or document. ‘Capture’ then represents listening and learning, and ‘Access’ is the dialogue involved in asking and answering questions.

It is also helpful to think about the model in reverse, that is, if you want to ‘Use’ knowledge then you need to be able to ‘Access’ it. Effective ‘Access’ requires effective ‘Organisation and Management’ and so on back round the cycle to ‘Create’. This mental model therefore helps to set the context for effective systems and processes.

The right hand side of the cycle is predominantly a push process: pushing the knowledge out so that it can be available. The left hand side is a pull process: seeking out the necessary knowledge.

Finally, although the ‘Create’, ‘Capture’, ‘Access’ and ‘Use’ stages require systems and processes to help them function, they are predominantly cultural challenges: they are about getting people to work in a different way. The ‘Organise’ stage usually requires some additional investment which can often be neglected or ignored. Information Technology investment may be required to provide a knowledge base that can be widely accessed, and personnel required to establish processes, provide training, manage the lifecycle of content or facilitate knowledge sharing. The availability of these resources and the achievement of the cultural change will again depend on the change enablers that we explore further in Chapter 7.

LEARN BEFORE, DURING AND AFTER

If the Knowledge Cycle provides the ‘what’ for Knowledge Management, there is another approach that provides the ‘when’. The approach developed by BP of ‘Learn Before’, ‘Learn During’ and ‘Learn After’, described in Learning to Fly (Collison and Parcell 2004), is central to almost every Knowledge Management practitioner’s approach that we have come across. Collison and Parcell represent these three steps in the form of a continuous loop, which closely matches the Knowledge Cycle. Learn Before mirrors the left hand side of the circle, that is, ‘Access’ and ‘Use’. Learn After echoes the right hand side of the circle, that is, ‘Create’ and ‘Capture’. Learn During embodies the whole cycle.

The Learn Before, During and After mental model reinforces the message that Knowledge Management is at the core of our work. It is also a good prompt for project managers, or anyone starting a new task or activity. They can ask themselves the question: ‘Before I start, what can I “learn before” from others who have done something similar?’ And the same applies for Learn During and Learn After, although in those cases they would also be asking themselves the question: ‘What have I learnt that I could usefully share with others?’ With this approach, people can look for and be given the appropriate ‘just in time’ tools, training and support that they need, and perhaps be given support through implementation. This is a better approach than to go through training in a number of tools, only to have forgotten about them, or forgotten how to apply them, when the time comes. We describe the techniques associated with Learn Before, During and After in Chapter 2.

Linking Knowledge Management to Business Strategy and Goals

Any serious attempt at Knowledge Management requires resources, effort and commitment. These can only be obtained if senior management is committed to supporting KM, and this commitment is best gained and demonstrated when Knowledge Management initiatives are aligned with the business strategy and play a key role in delivering its goals and objectives.

According to O’Dell (O’Dell, The Executive’s Role in Knowledge Management 2004), typical business objectives from which a business case for a KM initiative might be developed include:

• improved quality of products and services;

• building on lessons learned and shortening the learning curve;

• increased profitability;

• lower operating costs;

• innovation;

• re-use of past designs and experiences.

Clear business objectives such as these act as the basis for identifying what knowledge the organisation currently has to support its objectives, what knowledge it needs, and how it might go about addressing any gaps in a way that can be sustained. The business may also have some specific issues that it needs to address in which Knowledge Management tools or processes can play a role. Typical examples include:

• The business is concerned about a wave of retirees, or the potential loss of key people to competitors, with a consequent significant loss of knowledge. In this case a Knowledge Retention programme might help.

• Operational efficiencies are low or variable across an organisation. There is a potential to learn from each other and the facilitation of Best Practice transfer would help this.

• The business suffers from repeated failures in a particular area, implying that learnings are not being identified or are being forgotten. After Action or Learning Reviews can identify remedial action and improvement of internal processes.

A focus on the contribution of KM to the achievement of business objectives, combined with quantitative or qualitative measurement of the impact of related initiatives (KPIs), will make results more visible and help to foster the new behaviours and ways of working required to encourage and sustain change.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

The measurement of the performance of some areas ...