- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

More centrally focused on the Caribbean than any other survey of the region, Caribbean History examines a wide range of topics to give students a thorough understanding of the region's history. The text favors a traditional, largely chronological approach to the study of Caribbean history, however, because it is impossible to be entirely chronological in the complex agglomeration of often disparate historical experiences, some thematic chapters occupy the broadly chronological framework. The author creates a readable narrative for undergraduates that contains the most recent scholarship and pays particular attention to the U.S.-Caribbean connection to more fully relate to students.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Caribbean History by Toni Martin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Original Peoples

THE ISLANDS

The term “Caribbean” is normally understood to embrace the thousands of islands, large and small, which stretch like stepping-stones from Florida in the north to the northern shores of South America. To their west the islands are washed by the waters of the Caribbean Sea, which is itself enclosed by the Caribbean coasts of Central and South America. The waters of the mighty Atlantic Ocean lap the eastern shores of most of the islands. Further east is West Africa. There is practically nothing between the islands’ eastern shores and Africa.

In English-language history texts of the Caribbean, it has been customary to include Belize in Central America and the Guianas (Guyana, Suriname and Cayenne) in South America. This is because these mainland territories were traditionally closely tied administratively to Caribbean islands. Similar considerations to a lesser extent apply to Bermuda which, though geographically isolated far into the Atlantic, nevertheless shares much historically with Caribbean islands. The Bahamas are technically a separate entity from the Caribbean but are historically very much a part of the area.

The term “Greater Caribbean” can be used to describe the islands together with the mainland countries which border them. This textbook will follow the traditional practice of focusing primarily on the islands, the Guianas and Belize (though much more on the former than the latter). It is impossible, however, to ignore entirely the Greater Caribbean area. The larger area has always interacted with the islands.

The Caribbean islands are subdivided into three major geographical areas. The Greater Antilles comprise the four largest islands of Cuba, Hispaniola (shared between Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico and Jamaica. The Bahamas are the myriad islands that extend from Florida to the Greater Antilles. The Lesser Antilles consist of a string of smaller islands from the vicinity of Puerto Rico to Trinidad in the south. These Lesser Antilles are further subdivided into the Leeward Islands in the north and the Windward Islands in the south. Both these terms are leftovers from the days of sailing ships.

It has been customary, especially in the Lesser Antilles, to consider these islands “mere specks in the ocean,” insignificant to world affairs and lacking all potential to someday become world leaders. While it is true that some islands are little more than uninhabited rocks, it is also true that some at least of the islands are not nearly as small as their own inhabitants have been led to believe.

The problem lies partly in the Mercator projection map which has been the standard way of visualizing the world since the sixteenth century. This map, one of the great hoaxes of the colonial era, shows the Northern Hemisphere (especially Europe and North America), much larger in relation to the rest of the world than they really are. Areas in the Southern Hemisphere (e.g., the Caribbean, Africa and South America) are drawn much smaller than they are in reality.

These distortions have been remedied in the Peters maps, which will be preferred in this book. One glance at the Peters maps will establish how big or small areas are in relation to one another. It will be readily apparent that Cuba, for example, is nearly as big as England. Columbus recognized this fact immediately in 1492—in fact he thought that Cuba was larger than England and Scotland put together.

The islands are all within the tropical or subtropical zones and form a single cultural unit. Similarities far outweigh differences in topography, flora and fauna, local foodstuffs, lifestyle and cultural expressions. The broad sweep of history has similarly touched all the islands, at every stage of their development.

Today, for reasons which will become apparent in this book, the islands are home to a variety of racial and linguistic groups. Most territories are now independent, though some still remain attached, via one political device or another, to their French, Dutch, British or U.S. overlords.

FIRST NATIONS

The written history of the Caribbean began abruptly with Christopher Columbus’ European incursion of 1492. The people Columbus met were not literate and therefore did not document their history in writing. The picture available to us today of the pre-Columbian period is far from complete, but scholars have been steadily piecing together information on the lives of the first Caribbean nations. Information on these original people comes from three main sources, namely

1. The work of archaeologists. These have unearthed skeletal remains, remains of settlements and artifacts of all kinds. Archaeologists have also worked closely with scholars in other disciplines such as linguistics, geography and ethnography to try to reconstruct the lives of the original peoples.

2. The study of First Nations people who survived outside the Caribbean. The first inhabitants of the islands migrated primarily from South and Central America. Some of their distant relations, as it were, still live in places such as Guyana and Venezuela. It is possible by observing the languages and cultures of these survivors to catch an occasional glimpse of their earlier Caribbean counterparts.

3. The observations of the first Europeans. It is unfortunate to have to rely heavily on the testimony of Columbus and his compatriots since, however useful their observations, they were still outsiders looking in on cultures they did not always understand. Still we are greatly indebted to the early European historians, conquerors, priests, administrators and travelers for documenting the lifestyles of the original inhabitants. They thereby provided at the very least, a body of material to sift through and analyze, if even all of it cannot always be uncritically accepted as self-evident truth.

It was not long after 1492 before a few native peoples were born and raised in Spanish colonialism, complete with literacy in the Spanish language. In an ideal situation, these should have been a perfect group to record in writing the history and culture of their people. Unfortunately, however, as will soon be shown, by the time they came along, their people were already being rapidly exterminated. This extermination was virtually complete before there was time for a stable literate native community to emerge in the islands, with the facilities and leisure to document the history of their own people.

An obvious place for a literate class of indigenous historians to start would have been the areytos (or arietos), which survived the early years of the Spanish invasion. Areytos were songs accompanied by dance, in which people sang of the history and genealogies of their community. These ceremonies could go on for days and were reminiscent of the recitations of the traditional griots of West Africa who likewise memorized the histories of their communities. Bartolomé de Las Casas, most illustrious of the pioneer Spanish historians of the area, enthused over this form of oral history. “They remember these songs better,” he observed, “than if they had written them down in books.”

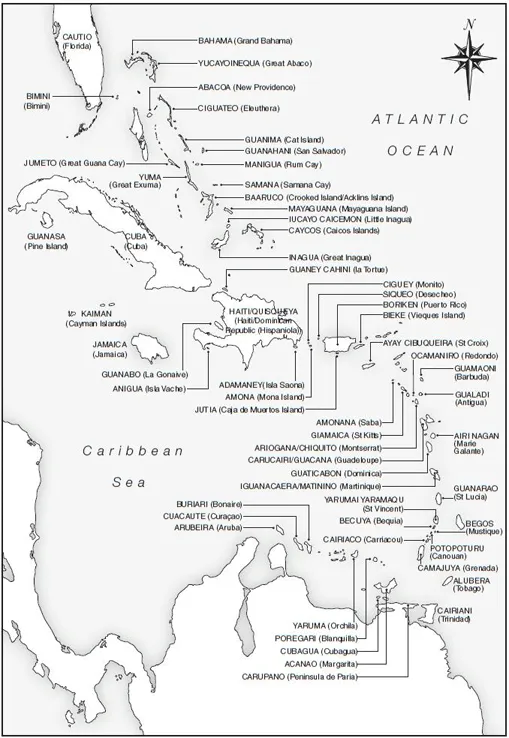

Map 1-1 Indigenous Names for the Caribbean Source: Based on Sued-Badillo, Jalil, Ed. General History of the Caribbean, Volume 1: Autochthonous Societies. London: Palgrave Macmillan; Paris: UNESCO, 2003.

It has traditionally been asserted that Columbus in 1492 met two major groups of indigenous people in the Caribbean. These were the Arawaks (usually called Tainos in the Spanish-speaking territories) and the Island Caribs (so named to distinguish them from their Carib cousins in South America). The Arawaks lived primarily, though not exclusively, in the Greater Antilles, the Bahamas and parts of Trinidad. The Caribs lived mainly, though not exclusively, in the Lesser Antilles. The Caribs were relative newcomers to the islands. The Arawaks and their predecessors had inhabited the islands for perhaps 7,000 years or thereabouts.

Archaeologists have argued among themselves as to whether the terms “Arawak” and “Taino” are appropriate for the Caribbean in 1492. Some argue that the alleged Island Arawaks were in fact far removed from their distant Arawak forebears from South America. They argue that the term “Arawak” is a catch-all for a variety of Caribbean peoples who were, in 1492, at differing stages of development. Some suggest that the term “Taino” is less inappropriate than “Arawak” since it connotes a common linguistic tradition, rather than a homogenous cultural grouping.

Those who challenge the suitability of the terms “Arawak” and “Taino” have come up with a bewildering welter of alternative designations. Instead of a single Arawak or Taino population, they propose a fragmented assortment of Huecoids, Ortoiroids, Casimiroids, Saladoids, Barrancoids, Troumassoids and others, all defined by styles of pottery found at various archaeological locations. Some of these groups are said to have been extinct, at least as culturally unique groups, in 1492. Others were assimilating into a newly developing Taino culture.

For reasons of convenience, this text will continue to designate as Arawaks and Tainos the indigenous people who greeted Columbus in the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. The terms will be used interchangeably. The Caribs will continue to be considered a separate group. Columbus is said to have encountered the last remnants of a third group, the Siboneys, in Western Cuba. The existence of these people is also a matter of dispute among archaeologists. Some suggest that if the Siboneys did exist they should more properly be termed “Guanahatabeys” or “Guanahacabibes.”

The first known human beings in the islands lived in Trinidad about 6,000 BC. Archaeologists have examined their remains at the Banwari Trace site in Trinidad. Their pioneering presence may be linked both to Trinidad’s closeness to the South American mainland, from whence these first arrivals came, and to the fact that Trinidad was joined to that mainland at various times in the past. People were living in Cuba by around 5,000 BC.

These early Trinidadians were part of a so-called Archaic immigrant group who continued into the Leeward and Windward Islands. They eventually merged with later immigrants.

A subsequent wave of new immigrants, among them so-called Huecoids and Saladoids, entered the area from South America. The Saladoids reached Puerto Rico by at least 430 BC. They continued into Hispaniola.

By around 400 AD, the various immigrant groups had sufficiently interacted to form the basis of a developing Caribbean culture. This process was well underway in 1492 when the invading Spaniards interrupted the process and destroyed the first Caribbean peoples.

Despite the inevitable differences over time and between locations, all of these communities shared much in common. They cultivated cassava and corn (maize), relied heavily on the sea for food and travel, traded with others in the region, fashioned implements and jewelry of stone, bone, wood, shell and mother of pearl, inhaled tobacco or other drugs, lived in wooden houses (bohíos) around a plaza and manufactured pottery. By the time that the Europeans came along, they met a Caribbean community which had been evolving for a long time. In its more advanced areas, most notably Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, this community was on the verge of developing powerful states.

The first Spanish observers described hundreds of political leaders or caciques. As in Africa of the same period, or indeed Europe itself, the most powerful caciques ruled over less powerful ones in a sort of confederacy. What the Spaniards called the caciques majores were akin to paramount chiefs in Africa or kings and emperors in Europe. The caciques under them would correspond roughly to the barons and earls of Europe and the lesser chiefs of Africa.

There were five major kingdoms (cacicazgos) in Hispaniola in 1492. They were Jaragua, ruled by the cacique Behechio, Maguana, ruled by Caonabo, Marien ruled by Guacanagari, Magua under Guarionex and possibly a fifth, Higuey, under the cacica (female cacique) Iguanama. Hispaniola was also divided into five geographical regions, which did not necessarily coincide with political jurisdictions.

Caciques held tremendous power and combined both religious and political authority. Like African chiefs they sat on a duho or ceremonial stool. They wore various emblems of office. They alone were allowed more than one wife, having on occasion as many as twenty or thirty. There were no standing armies, but in time of war caciques could, according to Spanish reports, mobilize as many as 15,000 soldiers in Hispaniola and 11,000 in Puerto Rico. The islands lacked iron and steel. The most potent weapon at their disposal was therefore the poison-tipped arrow. Spanish armor provided some protection, but Oviedo in the 1520s reported that the Spaniards had still not found an antidote to this poison.

Caciques could order soldiers into suicide missions. The early Spanish historian Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo claimed that caciques on the Greater Caribbean mainland would occasionally themselves commit suicide in order to induce some of their subjects into the act.

Caciques lived with their extended families in large dwellings. They also maintained a caney, a spacious building for receiving important dignitaries. They constructed and maintained such public works as roads, ballparks and irrigation schemes. Succession was matrilineal. This meant that neither the cacique’s son nor his wife inherited. Instead, inheritance passed to the cacique’s mother’s children, that is, to the ruler’s brother or sister, or thence to the mother’s nieces or nephews. If there were no heirs, then elections determined a successor. When caciques died, their possessions were distributed among mourners. Food was buried with them, to sustain them on their journey through the afterlife.

Most of the indigenes in the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas spoke the same language. The only exceptions were western Cuba, presumed home of the Siboneys/Guanahatabeys/Guanahacabibes and two isolated areas in northeast Hispaniola.

The Caribbean people were expert mariners. They had plied their waters for thousands of years. They knew the wind and ocean current patterns and were intimately familiar with the geography of the region. Here, as in Africa, Asia and elsewhere, local mariners were of invaluable assistance to European explorers. The Lucayos of the Bahamas showed Columbus how to get to Cuba. The indigenes told him that Martinique was one of the most easterly of the islands and therefore a convenient departure point for the journey back to Spain. In the Azores on the way back from Columbus’ first voyage, two captured Arawaks drew him a map of the islands using beans. Native mariners such as these were the largely unsung heroes of European exploration. Columbus did, however, acknowledge them in a letter written at the end of his first voyage. “They are of a very keen intelligence,” he wrote, “and men who navigate all those seas, so that it is marvelous the good account they give of everything….”

The local vessels were dugout canoes of various sizes, made from the trunk of a single tree. After his first voyage, Columbu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Map

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Original Peoples

- Chapter 2 The Coming Of Columbus

- Chapter 3 The Northern European Challenge to Spain

- Chapter 4 The Africans: Long Night of Enslavement

- Chapter 5 The Enslaved and the Manumitted: Human Beings in Savage Surroundings

- Chapter 6 The Big Fight Back: Resistance, Marronage, Proto-States

- Chapter 7 The Big Fight Back: Suriname and Jamaica

- Chapter 8 The Big Fight Back: From Rebellion to Haitian Revolution

- Missionaries

- Chapter 10 After Emancipation: Obstacles and Progress

- Chapter 11 Immigration in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

- Chapter 12 The Caribbean and Africa Through the Early Twentieth Century

- Chapter 13 The United States and the Caribbean to World War II

- Chapter 14 Twentieth Century to World War II: Turbulent Times

- Constitutional Advance

- Chapter 16 Prognosis

- Credits

- Index