Why is managing the policy process important?

With recurring environmental and financial crises, terrorism, continuing widespread poverty and inequality, and deepening concerns about climate change, the need for sound public policies has never been greater. Contemporary economic, social, and technological changes make the need for good policy and governance yet more vital. Addressing problems related to these issues and others necessitate governments to rise to the challenge of devising more effective policies.

These kinds of problems are too vast for communities and corporations, much less individuals, to resolve on their own: only governments have the potential to address such collective issues, especially when they work constructively with other governments and nongovernmental actors to do so. Organizing and managing the policy processes involved at national, sub-national and international levels is a critical task and an important harbinger of successful policy-making and effective policy outcomes.

Understanding policy processes and policy-making activities and the behavior of key actors is thus essential for policy actors aspiring to influence policy development in a positive direction. This book seeks to provide key policy actors in government and in nongovernmental positions with lessons found in the many works in the policy sciences that deal with these issues and questions.

Empirical research, for example, shows that government policy and governance institutions are the strongest determinants of development, both economic and social (Lin and Chang 2009; Haggard and Kaufman 2016; Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi 2004). Conversely, weak institutions and the bad policies they often produce are commonly the largest determinants of development failures. Thus, in the mid-1950s, income, education, and health indicators for Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) and South Korea, for example, were broadly similarly, but within only a decade all these indicators were much higher in South Korea, largely due to the policy institutions and practices found in that country which allowed effective policies to be developed, enacted, and implemented. Success bred further success in Korea while interlocking policy, governance, and development failures in Myanmar deepened over several decades (Holliday 2012). As these two countries show, the rewards for enacting sound policies through effective management of the policy process are as high as the costs of getting them wrong; and the long-term performance differentials generated by policy choices made today can be staggering.

The surest way to ensure effective policies are made and implemented is to build institutions and processes for making and implementing them that avoid common errors and replicate the conditions and practices needed for success. How this can best be accomplished is what this book is about. The book is for all stakeholders involved in the policy process. It is built upon the premise that policy actors can overcome existing barriers that undermine their potential for contributing to policy success. To do this requires that they better understand the requisites and institutional supports for effective policy-making, and identify and seize opportunities to leverage their positioning within often crowded policy-making processes to influence outcomes.

A difficult policy world: the challenges of governance

Governments face many challenges in contemporary policy-making (see Van der Wal 2017). One growing concern is the increasing “wickedness” or complexities of policy problems. Uncertainties have always plagued policy-making. But the ability to predict how policy x will affect problem y and associated issue z over time has been increasingly seen as strained to the breaking point by:

- the ever widening interconnectedness of problems;

- the expanding range of actors and interests involved in policy-making; and

- a relentless acceleration in the pace of change and decision-making (Churchman 1967, Levin et al. 2012).

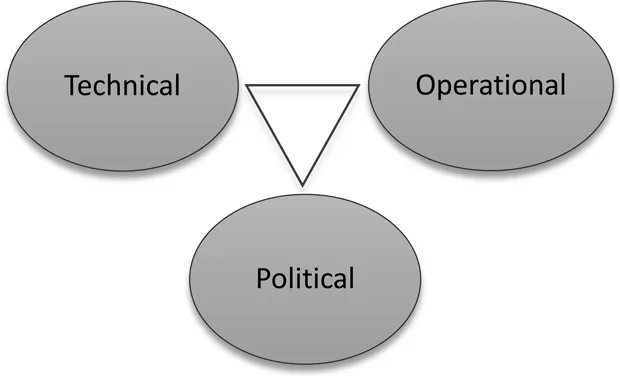

Another factor which makes policy-making increasingly difficult is the fragmentation in many countries of the societal, political, and policy institutions traditionally charged with organizing collective action in government. The polarization and fragmentation of public aspirations, ever rising expectations of government, and secular declines in public confidence and trust in government institutions also compound the challenges facing policy-makers. Together these institutional, political, and policy realities create what has been termed “super-wicked” problems, which pose three types of challenges to policy actors inside and outside government:

- political challenges linked to the need to gain agreement from key actors and the public on policy direction and content;

- technical or analytical challenges related to determining the most effective course of action; and

- operational challenges linked to effectively developing and implementing policy choices (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Policy challenges

Each of these three challenges is discussed in detail below and in the chapters which follow.

Political challenges

Policy-making is a quintessentially political process in that it affects who gets what, making it vital for policy actors to understand the political implications of their actions (Lasswell 1958). Merely understanding policy-making as an analytical exercise—identifying the costs and benefits of different policy alternatives, for example—is not enough; policymakers need also to come to grips with the political dynamics underlying the policy activities in which they engage. Successful policy actors need to survey the policy-making fields in which they themselves are situated, and in doing so:

- identify other actors involved in and affected by policies and policy-making;

- map out their essential interests, ideologies and relationships; and

- assess the waxing or waning of their sources of power and leverage within the process.

Policy-making is embedded in a world of formal and informal political compromises and deal-making. Policy actors need therefore to understand how and why to compromise—to acknowledge the trade-offs between policy theory and practice that may be needed to secure agreement among contending actors and interests on a particular course of action that government or other strong policy actors may desire. Indeed, policy actors may need to help craft such compromises, or to manage their consequences.

Consider (as we do throughout this book) the possible causes of policy failure. Ineffectiveness might on the surface stem from the poor design of an individual policy, or from incompetent or weak administration of the same. But often the real cause lurks elsewhere—in the failure to recognize and manage the contending interests of other policy actors. Examples are legion across levels and agencies of government itself, and may be magnified when government works cooperatively with the private or civil society sectors to formulate and implement policy.

Disagreements between different levels of government, if left un- or poorly managed, can also lead to contradictory policies that are mutually destructive of the aims of all. In federal countries, for instance, one level of government may promote coal extraction to produce electric power while another level tries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Scharpf 1994), a situation which requires management if either aim is to be achieved.

Within a single level of government, the goal of any given policy can be thoroughly clouded or undermined by the desires and strategies of different government agencies, each quite “rationally” pursuing incompatible or contradictory agendas. This is commonly the case, for example, where one ministry wishes to pursue an ambitious expansion policy in health or social welfare spending while fiscal gatekeeper organizations such as finance ministries or treasury boards wish to curtail budget deficits or government spending. Or agriculture ministries may continue to promote agricultural production at the expense of decreased water availability for industry and households, which may themselves be the subjects of major expenditure initiatives by ministries of public works and infrastructure expected to increase the latter (de Moor 1997). Again, such conflicts need to be anticipated and managed if either aim is to be accomplished.

It is also often the case that policies are formulated by governments and political parties in order to secure the support of politically powerful groups of economic or social actors at the expense of long-term public interests that may be underrepresented in the political system (Bachrach and Baratz 1970). In many countries, small groups of agricultural and business elites, for example, often exercise a virtual veto over reforms aimed at redistributing land or improving wages and working conditions for the large majority of the population (Patashnik 2008). But even where such conditions do not exist, political actors may try to appease clients in society and earn their support rather than act in the interests of the public at large.

Consideration of the political context in which policy-making occurs also helps us to understand why some policies are adopted despite having virtually no chance of having an impact on the ground at all. So-called “ideological” or symbolic policies are often used by political elites to cement their legitimacy among key supporters. With multiple ambiguous, non-prioritized, and largely non-measurable goals, such policies have little chance of being effective in achieving any but political constituency-building aims.

Technical challenges

In addition to the very significant political challenges, governments also face a variety of technical and analytical challenges in understanding policy problems and their root causes, and in devising solutions for them based on realistic estimates of future effects and outcomes (Pollock et al. 1993). There is often not enough information available on the historical or even current situation encountered by a government for it to fully specify the nature and scope of the policy problem itself, let alone its solution. Nor are the analytical tools that would help analyze available information, isolate cause and effect relationships, and inform effective policy action always available (Howlett 2015; Hsu 2015). In many countries and contexts, the available information and analytical tools are often manifestly inadequate in dealing with the growing complexity of problems (Parrado 2014). And the difficulties in acquiring and analyzing information are compounded by not knowing what to do with the findings.

Take the obesity problem in many countries as a good example. We know what causes it (high caloric intake and insufficient physical activity to burn it) and what the population needs to address the problem (fewer calories and more activity). What we do not know is what can be done to discourage the population from consuming more calories than they can burn (May 2013). Another example of a problem with high behavioral (and other kinds of) uncertainty is global warming and the adaptations necessitated by the ensuing changes in our climate. An even more immediate problem is terrorism; it has so many different origins and manifestations that it is impossible to devise solutions that would stymie all potential individuals and groups from turning to terrorist activities (May et al. 2009).

Such uncertainties need to be managed and, if possible, overcome. But policy-making in many countries is not helped by the generalist character of civil services found in them. Inherited from earlier times when problems were less pressing and complex, or when general expertise was adequate for most issues governments faced, public servants in many countries are still not generally expected, much less required, to be subject experts. This is notwithstanding the classic conception of the public service as being composed of “specialists” assisting “generalist” political masters. The reality is that most civil servants lack even basic training in the substantive areas in which they work (Howlett and Wellstead 2011; Howlett 2009) and often lack the skills and analytical competences needed to plug the information gaps and related uncertainties that plague decision-making and policy formulation and implementation. The health care sector, which attracts nearly one-tenth of global GDP, for example, is largely managed by public servants who lack both training and extended experience in the sector. Similarly, pension systems—another big budget item for most governments—are typically run by managers who lack basic training in actuarial estimates or in the politics of pension reforms (Stiller 2010). Policymakers need to address these technical capacity gaps if policies are to be effective.

Operational challenges

In addition to these political and analytical hurdles, policymaking also involves serious operational challenges. Organizing collective actions inevitably involves numerous individuals and agencies in complex deliberative and analytical processes. The making and implementing of effective policies require, at a minimum:

- well-defined administrative processes delineating the roles and responsibilities of different offices and agencies;

- adequate resources available for policies to be carried out;

- compliance and accountability mechanisms in place to ensure that all concerned are performing the tasks expected of them (McGarvey 2001); and

- the establishment of incentives that enforce not only minimum compliance on the part of agencies and officials with prescribed duties but also encourage them to seek improvements in their performance, something all too rare in many governmental organizations (Osborne and Gaebler 1992).

But making, implementing, and evaluating public policy is, of course, a collective effort. It is not sufficient for individual agencies and officials to function effectively. Governments need to ensure that officials and agencies work in unison towards shared goals. Coordinating and integrating the myriad efforts of large and diverse public agencies—across levels of government, and often in concert with actors in the private and non-profit sectors—is an extraordinarily difficult task (Vince 2015; Briassoulis 2005). Given that making and implementing policies almost always involves more than a few agencies, coordination is often hampered by such factors as:

- a “silo mentality,” whereby each agency focuses on its own core responsibility while ignoring the objectives of other agencies with whom they must cooperate to achieve an overall policy objective;

- different organizational cultures and standard operating procedures, which make it difficult for actors in a network to share information and resources, and to coordinate operational details; and

- the existence of multiple-veto points in many implementation chains, whereby an actor can stop or dramatically slow down joint efforts.

The interconnectedness of policy problems increasingly requires agencies established in earlier eras to coordinate their efforts in order to achieve policy objec...