![]()

PART 1

INTERPRETING INFRASTRUCTURE

Timothy Moss

INTRODUCTION: INFRASTRUCTURE SYSTEMS AND URBAN FLOWS

Water crisis in Yorkshire: During the summer of 1995 a severe shortage of rainfall in Yorkshire forced Yorkshire Water to tanker water into the region at a cost of £50 million. Freak weather conditions had destabilized the regional water network, causing Yorkshire Water temporarily to lose control of its management. The crisis had a lasting impact, however, in unsettling the complex social, environmental and technical relations that had shaped the way water was provided in the past. Customers rejected pleas by the recently privatized company to reduce water consumption, revealing an altered relationship between supplier and user after privatization. An independent inquiry subsequently set a new standard for measuring network stability, obliging Yorkshire Water to re-order its network to withstand worst-scenario drought conditions.

Planning a power plant in Copenhagen: In July 1996 the Danish Ministry of Environment and Energy rejected a proposal from the power companies serving the Copenhagen region to build a state-of-the-art combined heat and power plant (Avedøre 2’) to replace outdated electricity-generating capacity. The decision marked a milestone in Danish energy policy. For the first time, the environmental regulator had departed from the conventional supply-building logic, recommending instead a combination of demand management and decentralized generation where necessary. Against the arguments of the power companies SKpower and Elkraft that the new plant would reduce emissions substantially, generate electricity more efficiently and secure long-term supply, the ministry justified its rejection on the grounds that the plant exceeded predicted capacity requirements, countered national energy-saving targets and was less cost effective than alternative solutions.1

Competing waste-management strategies in Berlin: The fall of the Berlin Wall heralded a period of unprecedented uncertainty for waste-management planning in the Berlin region. A combination of major reform to national waste policy in Germany sharp shifts in levels of urban waste, competing technologies of waste treatment and political differences has caused plans for managing the region’s waste to be revised frequently over the past few years. Before unification West Berlin deposited its urban waste at low cost on East German territory. In response to calls from the new government of Brandenburg for Berlin to reduce the waste it deposited in Brandenburg by 50 per cent, three new incineration plants were planned by the city. However, as waste levels declined, more waste was recycled and resistance grew to the proposed plants, the plan was shelved by the new political leadership of Berlin’s Environment Department and a mediation procedure was established involving all interested parties – a unique step in waste-management planning in Germany.

All three examples illustrate emerging problems that are challenging the way technical infrastructure systems in Europe are managed. In the case of Yorkshire it is a crisis of supply set against the backdrop of privatized utilities; in Copenhagen it is the upgrading of physical infrastructure under stronger pressure for environmental protection; and in Berlin it is the re-structuring of technical networks to take account of shifts in the regulatory framework, consumption patterns and technological solutions. The responses to each of these problems mark a departure from previous, established strategies for managing infrastructure systems. Yorkshire Water has had to win back customer confidence and re-order its physical networks to meet new drought specifications. Copenhagen’s power utilities are having to practise demand side management instead of network expansion. Waste planners in the Berlin region are seeking flexible technical solutions (including waste reduction) to cope with planning uncertainties.

This book is about the transformation of infrastructure management in response to emerging new pressures and how this transformation is affecting the way technical networks shape material and energy flows in urban regions. Utility services for water, energy and waste influence the flow of a substantial proportion of the material and energy used in cities. They draw on external water and energy resources, distribute these in the required quality and form to consumers and dispose of waste products in and beyond the urban region. Power stations, water works and sewage treatment plants are key transformation and distribution points of anthropogenic material and energy flows, acting as nodes in a complex network. Cables and pipes are the lines which link these nodes, transporting large quantities of natural resources to and from the consumer. Infrastructure systems themselves require considerable energy and material resources to operate. Given their strategic importance in shaping the quantity and quality of urban environmental flows, technical networks offer enormous potential for minimizing the resource use and environmental impact of cities (BUND and Misereor, 1996, p225). Any efforts to make urban regions more sustainable will therefore need to exploit this potential better, understanding and using technical networks as instruments of sustainable urban and regional development.

In the past, strategies to improve the environmental performance of technical infrastructure systems have focused on technological efficiency and innovation, encouraged by state regulation and market incentives. The challenge to limit the environmental impact of utility services has been treated by urban planners and network managers primarily as a technical problem, to be solved via the application of the appropriate technology. However, recent difficulties in meeting the demand for natural resources, in financing network modernization and in planning infrastructure plant suggest that the root problem has as much to do with the way utility services are managed. It is becoming clear that existing structures, processes and logics of network management are often not conducive to resource conservation and pollution prevention. What is more, many instruments applied in the past to minimize resource use are not proving so effective under emerging new institutional frameworks of infrastructure management.

This introductory chapter first outlines the current process of transition in urban infrastructure, identifying recent pressures for change and indicating the implications of these changes for resource use and environmental protection. The following sections draw on the concept of flow management as an approach to sustainable resource use widely favoured in research and policy circles in recent years, demonstrating the value of the concept for understanding environmental flows and raising questions not answered adequately in the flow-management literature which have guided the research work presented in the book. The chapter then introduces the three urban regions where the case studies in Parts 2, 3 and 4 were conducted and concludes with an overview of the book’s structure.

EUROPEAN URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE IN TRANSITION

The dominant logic of network management

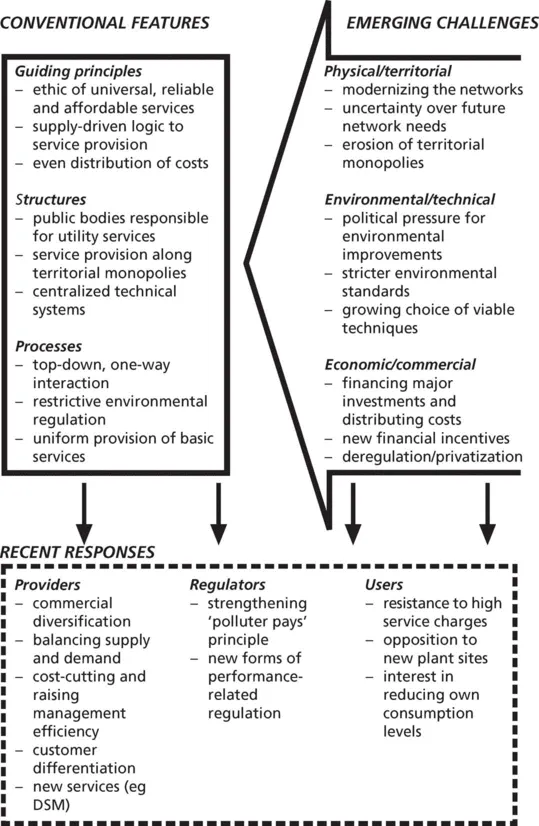

Until recently, infrastructure management in Europe has been dominated by a public service ethos to provide adequate and secure services available and affordable to all (see Figure 1.1). The overriding aim has been to build supply capacity and extend the physical networks in order to meet rising demand, maximize connection levels, avoid supply bottlenecks and satisfy higher performance standards. The predominant logic, or rationale, of ‘expand and upgrade’ has over the last century encouraged the development of large-scale, centralized infrastructure systems of extensive physical networks drawing on increasingly distant natural resources (Guy and Marvin, 1996; Guy et al, 1997).

Under this supply-driven logic there has been very little interest in shaping the intensity, time or place where demand is routed. Most utilities in Europe have in the past enjoyed a territorial monopoly over local services which has enabled them to plan long-term investments and distribute costs evenly among all consumers within their service area. Consequently, there has been little social or spatial differentiation in the treatment of consumers: prices for services in the past varied – if at all – only between commercial and household customers (Guy et al, 1996, 1997). Interaction between service providers and service users has been predominantly one-way and top-down; usually the only contact between provider and user has been in the form of the monthly or annual bill. Environmental improvements have followed regulatory pressures set by national or European Union (EU) bodies and, until recently, were directed more at minimizing emissions than reducing resource flows. Although regulatory and funding mechanisms have contributed substantially to raising environmental quality in recent years, their effectiveness has been limited by the fact that they have been interpreted largely in technical terms, they are often unresponsive to local specifics, they are cost-intensive and regularly fail to influence planning processes early enough to affect the outcome.

Source: IRS.

Figure 1.1 Urban Infrastructure in Transition

Within this general picture of conventional infrastructure management there are significant regional and sectoral variations. These would appear to depend primarily on the degree of local government responsibility for utility services, the regulatory framework, the market structure of each utility sector and the dominant technique or techniques used. Whereas, for instance, in the UK prior to privatization, infrastructure services were provided by distinct national and regional public bodies, in Germany and Denmark they remain a municipal responsibility operated by a large number of, often minor, actors.

New challenges for utility managers

The traditional logic of infrastructure management, however, is coming under pressure from a variety of emerging challenges. These new demands or ‘signals’ include primarily: the liberalization of utility service markets, the tightening of environmental standards, the high cost of network modernization, competition between a growing number of viable technologies, uncertainty over future consumption patterns and over-capacity in some networks. Infrastructure management in Europe is, as a result, undergoing major transformation on several distinct, but interrelated planes. The pace and nature of this transformation process vary considerably according to regional and sectoral specifics – the different degree of privatization of utility services in the UK, Germany or Denmark is one clear example; the high degree of social subsidization in Greece is another. The important point, though, is that the emerging challenges are affecting all utility managers, whether public or private, local or supra-national, creating tensions with traditional forms of infrastructure management.

If we read these signals in terms of their impact on urban environmental policy we might expect to detect new opportunities for resource conservation and new obstacles to past environmental strategies. For instance, the current modernization of water, sewage, electricity or waste infrastructure offers the chance not only to improve environmental performance but also to limit resource consumption through demand side management, particularly where demand threatens to exceed existing capacity. Conversely, stagnating or unpredictable demand – as detected for sections of the water and electricity networks in Germany and Denmark – question the conventional supply-oriented logic based on steadily rising consumption. Here, though, the immediate effect may be in the opposite direction, maximizing under-utilized existing infrastructure.

Recent responses by the actors

Combined, these new challenges are changing the context of infrastructure provision, forcing network managers to rethink how resources and networks are managed (Guy et al, 1996, 1997; Guy and Marvin, 1996). An important task of this book is to illustrate how different actor groups are responding to these signals in the way that they provide, regulate or use utility services and what openings these responses are creating for more efficient forms of resource use. On the basis of recent experiences a number of key research questions can be formulated relating to each of the three main actor groups.

Utility companies: commercialization and customer differentiation

Under the new competitive climate, utility companies are cutting operational costs and improving management efficiency. In the case of the larger companies they are also diversifying and widening their commercial interests into other utility sectors as well as into other countries. A new logic of differentiation in the treatment of customers would appear to be slowly developing as utilities seek to capture or retain lucrative customers, resulting in more reciprocal and dense relationships between producers and select consumers (Guy et al, 1997). The salient questions here are:

• What new opportunities for minimizing urban environmental flows are emerging from the growing shifts towards commercialization and customer differentiation?

• How do pressures to limit investment costs and reduce service prices encourage utilities to use and sell less water or energy?

• What options are being created for integrating alternative environmental technologies into existing infrastructure networks as a result of new regulatory, technological and institutional pressures?

Regulators: searching for new environmental instruments

In response to the above trends the bodies responsible for regulating the environmental and economic performance of utilities are seeking new constraints and incentives capable of stimulating resource conservation and pollution prevention under the shif...