![]()

1

Where We Came from and Where We are Now

In Will Steacy’s striking photo-essay ‘Deadline’, the slow decline of the Philadelphia Inquirer is captured over five years. Beginning in 2009, Steacy photographed the newsroom through shrinking sales, bankruptcy, and round after round of staffing culls.

His father was among those to lose their job as the newspaper, founded in 1829, shed staff like a second skin: from around 700 employees in the 1990s, to just over 200 by the time Steacy began his project. In his online introduction, Steacy (2016) writes about newspapers as the “fastest shrinking industry in America” and laments the human cost of technological changes:

When we lose reporters, editors, newsbeats and sections of papers, we lose coverage, information, and a connection to our cities and our society.…The newspaper is much more than a business, it is a civic trust.

Steacy’s photographs of the decline of the Pulitzer-winning Inquirer could be seen as a visual metaphor for the wider decline of the newspaper industry in the US and elsewhere.

Perhaps.

While it is true that newspapers in the US and the UK have shed hundreds of thousands of jobs since 1990,1 and indeed that the industry has shed hundreds of newspapers,2 what we have also seen is a news business that has shifted and changed and evolved in directions unimaginable in 2009.

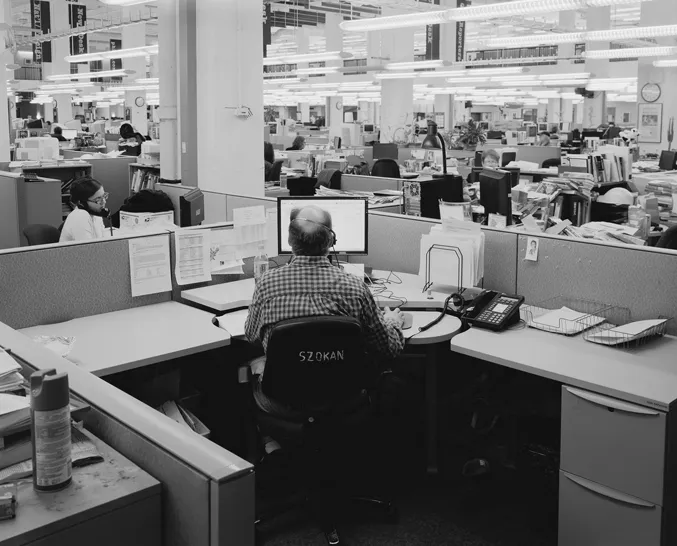

Take the picture in Figure 1.1 of Deputy Science and Medicine Editor Don Sapatkin in 2009. The desk is piled high with papers and books and notes, spilling out of boxes, wrapping around that bulky computer, drifting onto neighbouring desks. Almost a caricature of the working journalist.

Figure 1.1 Don Sapatkin, Deputy Science and Medicine Editor, 6:44pm, 2009. Photo by Will Steacy.

But this was not a photograph of a disappearing world, this was a photograph of a world that had already arrived.

In 2009, the World Wide Web had been public for 18 years, Google for 11 years, and Facebook for five. Twitter had been going for three years (Sapatkin himself joined Twitter in 2009), but Snapchat wouldn’t arrive for another two. Despite those piles of print, the Inquirer was already part of a world in which information and content was largely digital, public and shared.

By 2011, Sapatkin’s desk (Figure 1.2) had not only lost its paper mountain but Sapatkin had lost his place as primary source of public health news for his public, who now had access to acres of information online – much of it from the same sources he might use – and at the time they wanted to access it.

Sapatkin’s role was no longer just digging up health news stories and writing about them, but about finding those stories in new places and sources, and delivering the information in new ways. By 2015, he was marrying the fashionably new data journalism with old-style contact-chasing to deliver Clean Plates – an online project enabling instant access for the Inquirer’s readers to official restaurant inspection reports.3

Creating a restaurant report look-up tool may not sound like high-end, President-toppling journalism (although a mistake in reporting a restaurant inspection report provided a valuable lesson in journalistic technique for the pre-Watergate Bob Woodward4). But journalism delivers information stories as well as news stories, and knowing whether that restaurant where you plan to take your family has a clean kitchen is an information story that matters.

Figure 1.2 Don Sapatkin, 3:10pm, 2011. Photo by Will Steacy.

It’s that issue of how and why journalism matters that is worth hanging on to here.

Steacy’s photographs may have captured the slow death of newspapers, but that does not mean that journalism is also dying. Changing certainly, shrinking perhaps, but not dying. This book is called ‘Future Journalism’ because journalism has a future as well as a past.

While there may have been fewer job openings at the Inquirer in 2016, its summer internships programme included ads for “Digital Interns”, and an “Audience Development Intern” tasked with identifying social media influencers and spotting viral stories. The job of the traditional newspaper journalist has changed, but so too has the range and types of jobs in journalism. Today’s journalism graduate is just as likely to find her or himself monitoring a website’s comment threads as taking shorthand notes in a court case.

It is not just that the job of a journalist has changed, but that the nature of what it means to be a journalist – when we are “doing” journalism and when we might not be – is rapidly changing.

Coupon-clipping, coffee and money

While the future for the business models which fund the practice of journalism continue to shift and change, and for many individual examples have collapsed (goodbye Independent newspaper,5 hello and goodbye the New Day,6 goodbye crowdfunding pioneer Spot. Us7 and goodbye mobile news innovator Circa8), news still happens and journalism still matters.

There’s a video on YouTube from 1981 about the San Francisco Chronicle’s early foray into digital news.9 I love that video. Not only as an illustration of how much the technology of delivering the news has changed (taking two hours to deliver something not “spiffy looking” enough) but of that early arrogance of news workers in seeing the web as a quirky sidebar to their world, rather than the four horsemen and plagues of locust apocalypse it was to deliver.

In 1981, we were still ten years off the World Wide Web going public. However, the changes have not only been in the technology we use to deliver the news, it is the social change in the way we consume, share and interact with news that has had the biggest impact on the business of news.

Those Chronicle readers clipped out a coupon, posted it back to the newspaper, spent two hours downloading the basic text, then perhaps printing sections they wanted to save and read later, choosing to do all that rather than just have the newspaper delivered to their door.

They were not only e-newspaper reading pioneers10 but an early taste of our willingness to make a personal effort to seek out and gather information if it means we can control what we read and how and when we access it. That switch from largely passive receivers of news to largely active seekers and sharers of it has driven the change from traditional to digital media.

The process of journalism has changed alongside our behaviour as consumers of news. We expect news that we are interested in to be available to us whenever we want it and wherever we are. And the business of making money from journalism has had to fit into an open-all-hours shop-of-news model. And that can be expensive.

In the village next to the one I live in is a large Nestle factory. Nestle makes Nescafe, those Dolce Gusto coffee pods, KitKat, Crunch, Maggi seasonings, Carnation canned milk – and so on. The branding is in each product, rather than in the company. You know what to expect from an Aero or a Baby Ruth chocolate bar. You know which Nescafe coffee you prefer.

The business model is that you buy the Nestle products you like and, 130 years ago, that was pretty much the business model for newspapers. You bought the newspaper you found most interesting or entertaining or reflective of your thoughts, or a mixture of those. We do not pay a monthly subscription to drink Nescafe. Shopkeepers do not give us free chocolate bars in the hope that we will read the advert for insurance on the wrapper. We do not donate to Nestle because we want to support them in continuing to make the products we like.

But those models are all currently used in the news business: free newspapers making their money from adverts; paid subscriptions to access content beyond paywalls; donation and crowdfunding schemes to support individual journalists, stories, or news organisations. The picture is similar in broadcast news, with the majority paid for directly or indirectly through advertising.

As Nathan Rosenberg observed, technological change is “path dependent” (shaped by things that happen along the way) and industries bear the cost of that change, not just in R&D costs but in whether individual businesses, or sectors, survive the change:

The starting point for serious thinking about technological knowledge is the recognition that one cannot move costlessly to new points on the production isoquant, especially points that are a great distance.

(1994: 12)

But the biggest threat to journalism has come not from the changes in the technology or the readers’ expectations, but in changes within the business that journalism depends on – advertising. The traditional business model for journalism has not been to sell journalism but to sell the attention the journalism attracts.

News publishers have to do a lot of different things to get the attention they can sell to advertisers. They have to find or gather stories people want to know about; they have to present – tell – stories in ways that will make people want to read/watch/listen to them; they have to deliver those stories so people can easily find them. Finding and telling those news stories is generally what we think of when we talk about journalism.

But there is no direct profit for news publishers in producing journalism; it is a cost absorbed by that business in order to deliver the content that will attract the audience that advertisers will pay to reach. And, in a world in which advertising has become part of the problem – whether because of cut-price digital ads or the rise of ad-blocking software – both news publishers and freelance journalists are struggling to find models that might fill the gap left by shrinking ad revenue.

In 2012, US newspapers earned the same amount from advertising that they had earned in 1950.11 The income was the same but the cost of producing a newspaper was not the same as in 1950.

In 1837, it cost £690 ($860) to launch the Northern Star newspaper in the UK. Two years later, the national daily was delivering an annual profit equivalent to around £892,000 ($1.1 million) today, almost entirely from print sales. Contrast that with Lord Northcliffe’s estimate of the £500,000 needed to launch the Daily Mail in the UK in 1896; or the £2 million poured into Lord Beaverbrook’s Sunday Express after its launch in 1918 to get it to break-even profitability (Curran and Seaton, 2010). Or the £18 million investors sank into launching Eddy Shah’s technologically ambitious but doomed Today newspaper in 1986.

New printing technologies introduced in the 1880s onwards advanced mass circulation, but producing more newspapers required bigger operations, and bigger operations meant higher costs. News was an industry, and journalism, as a product of that industry, needed to be “sold” to a larger and larger consumer base to cover costs and return a profit. The Northern Star had to sell just 6,200 copies to break even, while Beaverbrook’s Sunday Express needed to sell 250,000 copies. The New York Times, with a print circulation of just under 1.4 million and 1.2 million digital subscribers in 2016, was still posting losses and cutting jobs.12

The issue is that the cost of producing a newspaper has outstripped earnings from newspaper sales since the 1880s. Since then, the business model has become almost entirely dependent on the delivery of an audience to advertisers – and the valuing of that audience according to both demographic and size. The assumption that equated size of audience to share of advertising revenue has been disintermediated by the audience shift to digital, and the value of an advert has been worn away with each technological iteration.

It should have been a neat equation – money from ads offline in newspapers, magazines, on TV and radio goes down, but online ad income goes up to fill the gaps. But while the online media of web and mobile have rapidly grown the audience for news, they have also devalued audience size as a metric. As media analyst Michael Wolff wrote:

The news business has been plunged into a crisis because web advertising dollars are a fraction of old media money. And mobile is now a fraction of web: the approximate conversion rate is $100 offline = $10 on the web = $1 in mobile.

(Wolff, 2012)

He was responding to a ...