![]()

Part A

My Story: Extracts from my journal

Having fair skin

Throughout a dreadful childhood and relationship I have gained the most precious gifts of all, a beautiful daughter and son. There is also an added bonus and that is my son-in-law and two little grannies. This is what I am grateful for.

‘Grateful’ was a word that annoyed me right the way through my childhood and I vowed, ‘I don’t need to hear it again.’ But I have to use it to justify how I feel today. I don’t ever want to forget that it was my two children who became my anchors in times of sadness, suicidal tendencies, rejection and identity crisis. That is why it is fundamental that I don’t get myself absolutely lost in the emotions of my losses. I cannot go backwards because it is too hard. My most treasured memories are of gaining this, my ‘first family’, as we have each other ‘through thick and thin.’

We are all born into this world as innocent babies. The decisions that are prepared for us can transform our whole lives, sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse. However, we can only live the life that has been given to us and make the most of it. The choice that was made for me may not have been the best but that is something I will never really know.

I have lived my life with shame, anger, low self-esteem and no confidence. But the worst of all has been living my life without knowing who I really am. This is something that most people know. You may ask why I don’t? I am a fair-skinned Aboriginal person who happened to be born at a time when the governments determined it was best for me to be removed from my parents, and my culture. And I was brainwashed into believing I was an orphan.

I haven’t had a lot of socialising at all with Aboriginal people, as I feel they are not the same as me in their way of thinking. I believe some think I am a ‘coconut,’ which means you are dark on the outside and white on the inside. Another reason has been my denial and identity crisis: I cannot openly say, ‘Yes, I am an Aboriginal person.’ Throughout my childhood, my upbringing in a white society taught me to have this type of attitude as a fairer child, regardless of my Aboriginality. This was the English teaching that was introduced to enable fair-skinned Aboriginal people to forget their identity and forget about their own families. It doesn’t mean that we classify ourselves as being any different; it’s what we were taught to believe as children. Now when anyone asks me where I come from, I just say ‘Australia,’ and leave it at that.

In 1905 an Act was passed to make provision for the better protection and care of the Aboriginal inhabitants of Western Australia. Later in 1936 another Act was passed in which Mr AO Neville, the Chief Protector of Aborigines, was made the legal guardian of all Aboriginal children. This Act has affected my life, because I was born in 1942.

Breeding out

Mr AO Neville was obsessed with the ‘breeding out’ of half-caste Aboriginal children. His basic idea was to encourage women with lighter skin colour to co-habit with nearby white men. Eventually this would eliminate any traces of Aboriginality. In order to do this he had to strictly control the lives and marriages of fair-skinned young women, so his policy was to segregate them from childhood from the influences of parents and culture.

Under this Act I was institutionalised for eighteen years. I entered Sister Kate’s Children’s Home (SKCH) at the age of two and left when I was twenty. The memories of my childhood are empty, with stubborn scars embossed in my heart that cannot be erased. Institutionalisation experiences can be traumatic for most children, irrespective of what colour they are. However for fair-skinned Aboriginal people, their identity, culture and family unity are stripped from them as they are prevented from associating with darker-skinned people.

Whilst living in the Home we were informed that we had no parents: ‘That is the reason why you are here in the Orphanage.’ We were also told we must be ‘grateful’ that we had ‘someone to care for us’ there. I’m not too sure what they meant about ‘caring’, but I certainly don’t recall being cared for. To be forthright I think we were subjected to abuse, mental trauma and rejection in all ways, so this is the form of caring we were given. They said this was being done ‘in the best interest of the child,’ that it was important that the children were raised according to white Australian standards.

Did anyone bother to ask us in later life whether this was the best policy? Absolutely not. Children who were taken forcibly by the Government were herded like cattle. The segregation of quarter caste, half caste and full blood was determined by the Government’s own interpretation of Aboriginality and who was an Aboriginal child.

However, how does one deal with these sorts of memories and the emotions they bring up? You can’t reason with this kind of behaviour and it definitely leaves you wondering how you cope without living in denial. Sometimes, the hate inside is unbearable, as you think, ‘Why couldn’t I be like any other person?’ I asked another girl from the Home once, ‘Why did God make us this way and why is it that life seems to be so hard?’ Her answer was, ‘God knew you could handle this situation and that is the reason why you are the person you are today. There are only certain people who have the strength to survive what you have gone through.’

Now I don’t really know if this is supposed to make me feel good or what?

Beginning the journey

Although we cannot change things that have happened, a journey of healing had to take place. This did not happen for me until I was 47 years old. It is an ongoing struggle of unearthing information, which through the years has taken its toll in many different ways.

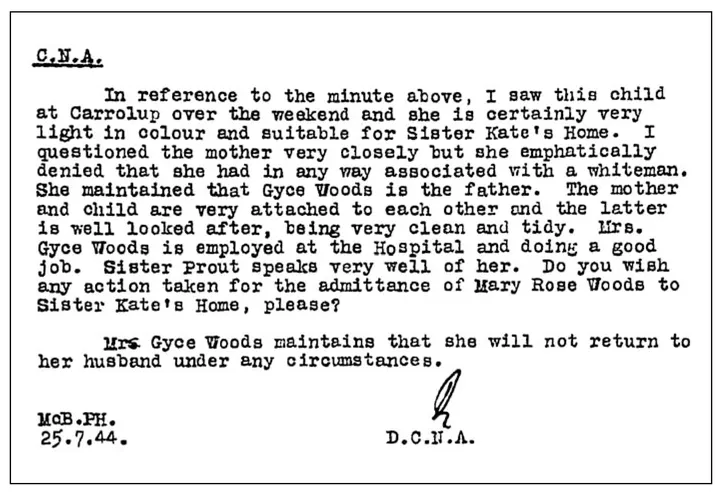

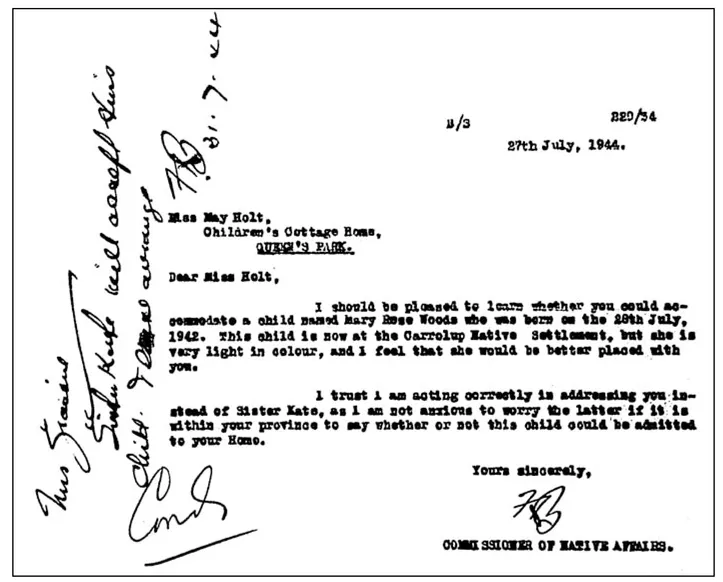

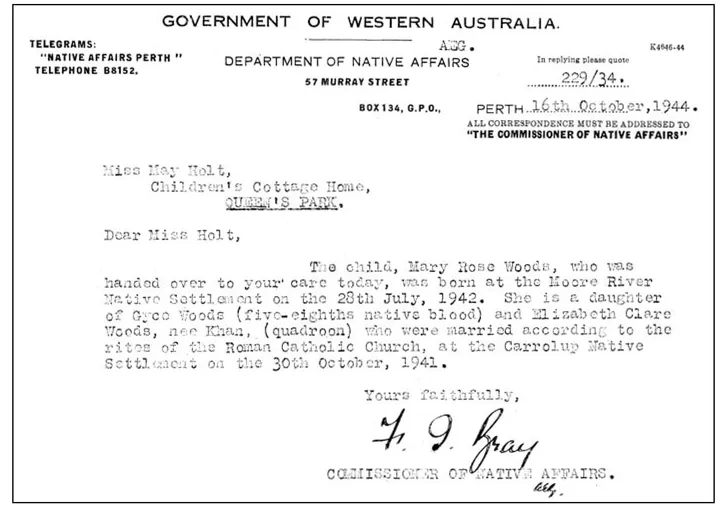

My first step was in 1988 when I decided to search for my government papers, which I received from Community Services in Western Australia. This was the most unexplainable feeling, to see such documents written about me and my life as a two year old, and to know that I was the subject of that policy of separating pale-skinned children from their parents. Until then I had been unaware of all the things that went on in those years. Through my Government Papers, I was able to find out where I was born and where I lived for the first two years of my life. The papers also gave me an insight into the type of person I was.

People, whether non-Aboriginal or Aboriginal, who have been raised with family and living with their own culture have a sound knowledge of their past and present situations. For most Aboriginal people who have been denied this experience, it generally means taking a trip to the library in search of what are known as ‘Government Papers.’ This is where I discovered things about myself.

Mixed emotions consumed me as I started on my journey to meet my mother and biological family. This didn’t happen until 1989 and again it was

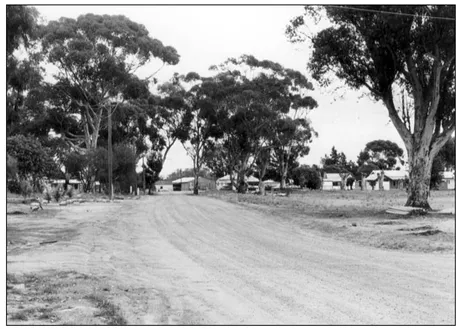

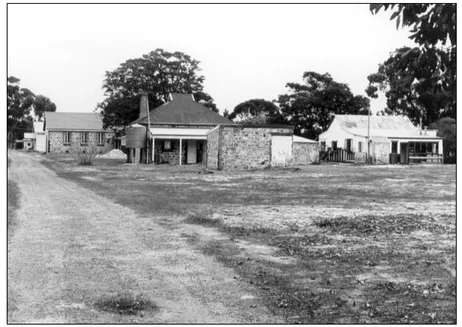

Entrance to Carrolup Mission (2001)

not quite the way I had imagined. Then again, I really don’t know how I had imagined it would be. The disappointment of who my Mum was shocked me, and I’m not happy with the way it turned out, but that’s how it is. I have been trying to accept that this is my Mum but it is a real struggle to deal with this issue.

The reuniting was something I felt I had to do at that stage in my life, even though I was not ready to deal with it then. I felt the best thing I could do was take a step back and really focus on what I was trying to do. This took me another 12 years (until 2002) to start to look at things differently.

Another big feature in the decisions I have made over the last 14 years was the break up of my relationship with my children’s father after twenty-two years. This gave me more freedom to be able to look at myself in a different light. I do sense that I was able to open up a lot of closed doors once I got over the hurt and humiliation of the separation.

Childhood memories

Now having said all this, whether memories are good or bad, there are always long-lasting memories after living in an institution for a period of eighteen years. These thoughts bring to mind happiness as well as emotional stresses.

The Government papers document that I was taken from Carrolup Mission and placed as an inmate, at the tender age of two, into SKCH. I have no recollection of my time with my mother, but I take it we had a good relationship as mother and daughter. Apparently I had sores so they had to be cleared up before my removal and placement into Sister Kate’s. I don’t know how I travelled to Sister Kate’s, but I presume it was by car. My arrival in Queens Park doesn’t come to mind, and there is absolutely nothing I can recall about the journey or who looked after me.

I will now share with you various memories and childhood pranks, and give some insights into life and routines in an orphanage.

There was a time when I was approximately four years old and I was clinging to another girl’s dress and crying as I didn’t want her to leave me. This created problems and I was in trouble and I was told I would get a good hiding if I didn’t stop. There was no way I could stop screaming or let go of her dress. It must have been a traumatic time; perhaps I was remembering when I was taken from my mother. From this I would say the separation from my mother had a terrible psychological impact on me as a little kid. My childhood wasn’t something that I could hold onto, cherish, and look back to and say, ‘Gee, I was so lucky to have had that childhood.’

Yarning for connection

One of the things that I think about was how we children used to sit in a circle and just wonder what our mum and dad looked like. This sort of thing happened a lot. We would wish our mum and dad were alive, and then we could see them. We were told so often that we had to be grateful to the Home for looking after us, that we had nobody else to care about us. One of the many things that annoys me is the lies we were told.

I can remember when other children would arrive at the Home. It was a common practice for the new children to group together in a circle on the ground. Many still talked in their own language, which we thought was strange. I guess this was how life had been for them with their own people.

Cold and cruel

As a child there was no nurturing at all. We had ‘housemothers’ who were looking for somewhere to stay till they found something more suitable. To be perfectly honest the housemothers were ‘a dime a dozen.’ The changeover was horrific and I couldn’t possibly tell you who looked after me as a young child. There was one housemother, Miss Gott, who gave three of us girls a good belting for hiding under the bed and screaming whilst a thunderstorm was on. I think this is the reason why I am petrified when there is a storm.

Unfortunately, the experiences I had with housemothers is not what a child imagines life to be. My memories are still raw concerning an incident during late October when the older girl of the cottage would wash and iron our white dresses to be worn on Fete Day. It was tragic as the cat had had kittens in the wardrobe where the dresses had fallen down. It was Saturday morning, washing day, so we had the fire going to boil the water in the copper. This wicked person made three of us girls throws the six kittens into the fire. Still today I can hear the squeals. Is it any wonder these children grew up with trauma and dysfunctions?

Another woman who did not last very long would call us girls in on Saturday afternoon to have a bath. She would sit in the corner and watch us, then sniff our pants and say we were dirty little girls. Honestly, how sick is that?

There were lots and lots of times when you would cry yourself to sleep with your head under the covers so nobody would hear you. If another child heard you they would automatically call you a big sook and nobody wanted to be laughed at. I can remember all of us kids having dirty noses, and you would be always in trouble when the big girls or the housemother would see you with big ‘candles,’ as they called it. We would naturally wipe our noses on our sleeves, but I think this annoyed the housemother, so we had a piece of rag pinned on us.

Dunny can

I can remember when I was only very small and still living in the Nursery cottage, we never had proper toilets; it was a dunny can and there was no chain. You had to use the toilet one after another. When you think about it today, how disgusting was that? One just cannot imagine how we coped, but then again we didn’t know any different, because that was what we grew up with. The Dunny Man would come on a Saturday and take the dirty can away and replace it with an empty one. Most of the time we used newspaper, because there was no toilet paper. Sometimes when we were in the bush and we needed to go to the toilet, we would use a woolly bush to wipe ourselves, as it was lovely and soft. Today when I see this particular bush it always makes me laugh; it certainly takes me back to when we were kids.

Chores

Every morning we would do our household tasks, attend church and then proceed to school. This generally made all of us kids run late for school assembly. This caused a lot of disruption at the school. Every day was more or less the same routine, except the weekend when Saturday was house cleaning, laundering and ironing. On Saturdays we would have our hair cleaned through with kerosene for nits.

Every day the boys milked the cows and one person from each cottage would go and collect their billycan from the shed where the boys separated the milk into the individual cans. You had to be very quick because this was our breakfast. If you dilly-dallied you would be in trouble. There was the housefather, Mr Towers, who would be waiting near the water tank at t...