- 142 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Using Feedback to Improve Learning

About this book

Despite feedback's demonstratively positive effects on student performance, research on the specific components of successful feedback practice is in short supply. In Using Feedback to Improve Learning, Ruiz-Primo and Brookhart offer critical characteristics of feedback strategies to affirm classroom feedback's positive effect on student learning. The book provides pre- and in-service teachers as well as educational researchers with empirically supported techniques for using feedback as a part of formative assessment in the classroom.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1

Formative Assessment and Feedback in the Classroom

The literature on formative assessment has increased substantially in the last 18 years. We can easily find definitions of classroom formative assessment in books and articles; however, frameworks that guide our thinking about formative assessments are rarer.

The goal of this chapter is to introduce you to a framework for thinking about feedback and formative assessment in the classroom. The framework was designed with two essential purposes in mind: (a) to provide a model for thinking about formative assessment and feedback in the classroom, and (b) to help conceptualize feedback in a context broader than oral or written comments in response to student work. This model then provides a way to organize the information presented in each of the subsequent chapters of this book.

We begin with a general discussion of formative assessment and feedback in the classroom that provides a larger context for a description of the major aspects of the framework. This discussion includes an overview of studies that were intended to evaluate the impact of feedback on student learning. We then describe the framework in detail. The chapter closes with a general discussion/overview of the role, purpose, and functions of classroom feedback.

Some Background in Formative Assessment and Feedback

Black and Wiliam (1998) defined formative assessment as “encompassing all those activities undertaken by teachers, and/or by their students, which provide information to be used as feedback to modify the teaching and learning activities in which they are engaged” (p. 7). In this definition feedback is a critical component of the formative assessment process. However, not all definitions of formative assessment include feedback. For example, Bell and Cowie (1999) defined formative assessment as the “process used by teachers and students to recognize and respond to student learning in order to enhance learning during the learning” (p. 198); and Shepard, Hammerness, Darling-Hammond, and Rust (2005) defined it as the “assessment carried out during the instructional process for the purpose of improving teaching or learning” (p. 275). The Assessment Reform Group (nd) in England proposed five elements of assessment. Feedback was included as one of these elements but it was not at the center of what the group called “assessment to improve learning.”1 Leahy, Lyon, Thompson, and Wiliam (2005) identify feedback as a strategy of formative assessment. In a more recent definition of formative assessment the term feedback disappears:

Assessment functions formatively to the extent that evidence about student achievement is elicited, interpreted, and used by teachers, learners, or their peers to make decision about the next steps in instruction that are likely to be better, or better founded, than the decisions they would have made in the absence of that evidence.

(Wiliam, 2011a, p. 43)

Whether the term is part of the definition or not, feedback is regarded as a critical characteristic of formative assessment. Different models have been developed to capture the essence of feedback in the context of formative assessment (e.g., there are models of formative assessment around feedback; see Heritage, 2010). Indeed, to evaluate the impact of formative assessment on improving student learning, researchers mainly cite studies on the effects of feedback.

A substantial literature of books and papers on the topic of feedback and its impact on student learning has accumulated over the last 20 years. Multiple meta-analyses have provided evidence of the effects of feedback on student learning. Feedback has been considered one of the most powerful interventions in education (Hattie, 1999) but also one with the highest variability in its effects (Hattie & Gan, 2011). Most of the recent meta-analyses (e.g., Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996; Van der Kleij, Feskens, & Eggen, 2015) and reviews (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Shute, 2008) have demonstrated positive effects on student learning outcomes (medium- to large-effect sizes), with a few exceptions showing small effects (Bangert-Drowns, Kulik, Kulik, & Morgan, 1991) and even negative effects (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996; Shute, 2008). Many resources present detailed results of these meta-analyses and reviews (e.g., Black & Wiliam, 1998; Brookhart, 2004, 2007; Mory, 2004; Shute, 2008; Wiliam, 2011a, 2011b).

Despite this accumulated evidence of the effects of feedback, it is difficult to determine clearly what specific types of feedback are effective (Shute, 2008). Furthermore, the overall results of the meta-analyses indicate that not all types of feedback are equally effective. Different issues account for this variability of impact. One of the major issues is that feedback has not been consistently characterized across studies (Ruiz-Primo & Li, 2013a). Feedback can be characterized, for example, by dimensions such as (a) who provides the feedback (e.g., teacher, peer, self, technology-based), (b) the setting in which the feedback is delivered (e.g., individual student, small group, whole class), (c) the role of the student in the feedback event (e.g., provider, receiver), (d) the focus of the feedback (e.g., product, process, or self-regulation for cognitive feedback; or goal orientation or self-efficacy for affective feedback), (e) the artifact used as evidence to provide feedback (e.g., student product, process), (f) the type of feedback provided around the task (e.g., evaluative, descriptive, holistic), (g) how feedback is provided or presented (e.g., written, oral, computerized), or (h) the opportunity provided to respond to the feedback (e.g., revise products). Few studies systematically address these specific characteristics of effective feedback in the classroom and in different disciplines such as science and mathematics education (Ruiz-Primo & Li, 2013a).

A second issue making it difficult to specifically identify effective types of feedback is that some of the meta-analyses grouped fairly dissimilar studies with diverse methodological quality. (e.g., Bennett, 2011; Briggs, Ruiz-Primo, Furtak, Yin, & Shepard, 2012; Ruiz-Primo & Li, 2013a). A third issue relates to the type of empirical evidence provided in many reviews and meta-analyses (Ruiz-Primo & Li, 2013a). The knowledge base about feedback is drawn mainly from studies conducted in laboratories or in artificial classroom environments where learning tasks tend to be minimally meaningful or relevant to learners, and they seldom study long-term feedback effects.

Despite the number of studies reported in the literature, the many models available, and meta-analyses on this topic, feedback practice still is often reported as one of the weakest components of teachers’ classroom assessment (Askew, 2000; Black & Wiliam, 1998; Ruiz-Primo & Li, 2004, 2013a, 2013b; Ruiz-Primo & Furtak, 2006, 2007). Even when “teachers provide students with valid and reliable judgments about the quality of their work, improvement does not necessarily follow” (Sadler, 1989, p. 119). Why? What is needed for feedback to have the expected positive effect on students’ learning and performance?

Six guiding premises are helpful in examining the role of feedback in formative assessment: (1) all learning involves interactions (e.g., Greeno, 1997; Hickey, 2011), (2) all interactions involve assessments because assessment is practiced within social interactions (Jordan & Putz, 2004), (3) formative assessment is a complex set of interrelated assessment practices (Cowie, 2005), (4) the function of formative assessment and feedback is to improve student learning (e.g., Ramaprasad, 1983; Sadler, 1989; Wiliam & Leahy, 2007), (5) for feedback to have a positive effect on student learning it must be useful and must be used (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Wiliam & Leahy, 2007), and (6) feedback becomes useful and used when it is planned in a proactive manner, rather than treated simply as the information provided to the student (and/or the teacher) in response to something that students did, wrote, said, made, or gestured. These guiding premises shaped the development of the framework for classroom formative assessment we describe in the next section.

A Conceptual Framework to Think About Formative Assessment

The framework we are presenting here is an adaptation of the framework that one of us (Ruiz-Primo, 2010) developed for a project funded by the Institute of Education Sciences (Ruiz-Primo & Sands, 2009), titled Developing and Evaluating Measures of Formative Assessment Practices (DEMFAP). One of the purposes of the project was to learn more about how formative assessment was implemented on an everyday basis in mathematics and science classrooms. The reason we adopt and adapt the framework is because we believe it can help you understand the different aspects involved in implementing quality formative assessment, which in turn can lead to applying feedback in useful ways to improve students’ learning.

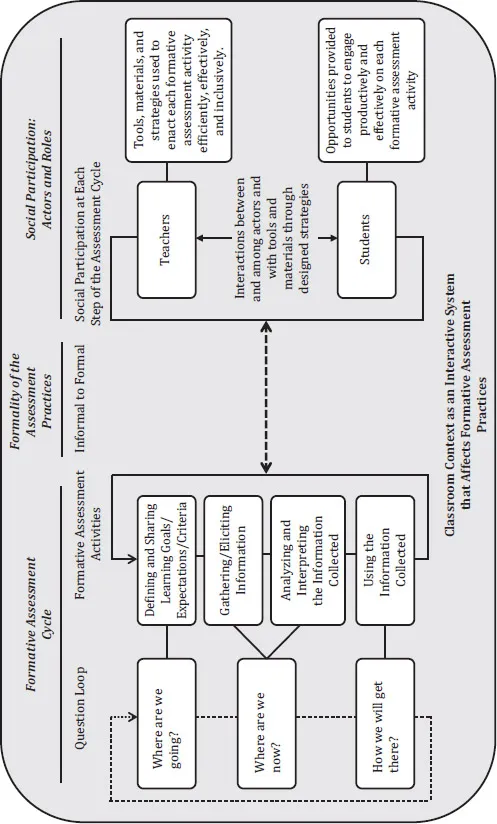

The proposed framework is based on theoretical perspectives, research, and practitioner knowledge. It brings together concepts that originated in the cognitive sciences, ideas about a sociocultural perspective of learning, and what research and practitioners have identified as important issues related to assessment for learning. The framework is based on the four pillars of the DEMFAP framework: assessment cycles or episodes, the formality of assessment practices, the teachers’ and the students’ roles at each step of the assessment cycle, and the context in which these activities occur. Figure 1.1 presents the dimensions of the formative assessment framework.

Figure 1.1 Formative Assessment Framework

Adapted from the DEMFAP framework; Ruiz-Primo (2010).

Theoretical Perspectives

Cognitive Perspective on Learning

There are two essential cognitive components to consider when thinking about formative assessment: cognition and regulation.

COGNITION

Cognition refers to the thinking activities that students use to process content and achieve learning outcomes. Teachers must keep student thinking in mind when they define the learning goals, select strategies to elicit information from students, analyze and interpret what they find, and respond to students. “Awareness of the role of cognitive process in assessment enables educators to obtain the maximum benefit from assessment activities and information” (Solano-Flores, 2016, p. 37). If you are aware of students’ cognitive processes, you will appreciate the importance of selecting or designing questions and tasks for students. How questions are posed will determine the cognitive processes most likely to be elicited from students. The quality of the learning activities in which students engage will determine the quality of the learning outcomes they eventually achieve (Vermunt & Verloop, 1999).

Different taxonomies tap different cognitive processing activities. The taxonomy created by Bloom and his colleagues (Bloom, 1956; Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl, 1956) is the most familiar in the field. Other taxonomies of cognitive processes exist. For example, Porter (2002) offers a classification of performance goals in mathematics and provides a language that is frequently associated with performance goals. An instance of a performance goal is communicate understanding of concepts. Porter proposes the following language to translate this learning goal: communicate mathematical ideas, use representations to model mathematical ideas, explain findings and results from statistical analyses, or explain reasoning. Webb (2007) provides a classification for judging curriculum standards and their alignment with assessments using the idea of depth of knowledge; from Level 1, which involves recalling information such as fact or performing a simple algorithm, to Level 4, which requires complex reasoning, planning, and developing over an extended period of time. Ritchhart, Church, and Morrison (2011) propose a list of high-leverage thinking moves that will engage students in deep understanding such as building explanations and interpretations, or reasoning with evidence, or making connections. Li, Ruiz-Primo, and Shavelson (2006) have proposed four interdependent types of knowledge that result from learning within a content domain: Declarative knowledge—Knowing that, Procedural knowledge—Knowing how, Schematic knowledge—Knowing why, and Strategic knowledge—Knowing when, where, and how to apply knowledge. The Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS, 2003) proposed three cognitive domains in science (factual knowledge, conceptual understanding, reasoning and analysis) and four in mathematics (knowing facts and procedures, using concepts, solving routine problems, and reasoning). The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) framework for assessing students (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2013) also provides some categories related to cognitive demands (e.g., students recognize, offer, and evaluate explanations for a range of natural and technological phenomena). Whatever the taxonomy being used, what matters is that it reflects the type of cognitive processes (thinking) you want students to use. Once you are clear on what these thinking processes are, you need to value and promote them in the classroom during both instruction and assessment.

REGULATION

Another concept addressed in the framework is regulation and its critical role in learning. “All theories of learning propose a mechanism of regulation … [] … equilibrium in Piaget’s constructivism, feedback devices in cognitive models, and social mediation in sociocultural and social constructivist approaches” (Allal, 2010, p. 348). The idea is that students regulate their learning process when they are involved in cognitive processing activities, in affective activities to cope with emotions during learning, and metacognitive activities to exercise control over the cognitive and affective activities to achieve the learning goals (Vermunt & Verloop, 1999).

Formative assessment plays a “pervasive role in the regulation of learning when it is integrated from the beginning in each teaching and learning activity” (Allal, 2010, p. 350). Feedback is a critical element at every stage of the regulation process: goal setting/orienting/planning, monitoring progress toward the goal, interpreting results from monitoring to adjust actions, and evaluati...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Formative Assessment and Feedback in the Classroom

- 2 Feedback, Goals of Learning, and Criteria for Success

- 3 Characteristics of Effective Feedback: Comments and Instructional Moves

- 4 Implementing Effective Feedback: Some Challenges and Some Solutions

- 5 Feedback Here, There, and Everywhere

- 6 Improving Classroom Feedback

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Using Feedback to Improve Learning by Maria Araceli Ruiz-Primo,Susan M. Brookhart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.