- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Energy in China's Modernization

About this book

A selection of 50 Slovak folk tales assembled from the collections of folklorist Pavol Dobsinsky. The translator seeks to preserve the poetic qualities of the originals, and the book includes an introduction to the genres of the folktale and the specifics of Slovak tales.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Energy in China's Modernization by Vaclav Smil in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Chinese Energy: Commonalities and Peculiarities

When China was rediscovered by the Western media, after the Nixon-Kissinger pilgrimage in 1972, numerous apologists for the Maoist regime tried hard to create the image of a country truly apart: an admirable, efficient society dedicated to economic advancement and well-being, a nation of vigorous growth rates, plenty of food, and a smile on everyone's face. And, a feat in such startling contrast to post-1973 Western woes, a nation with self-sufficient and vigorously expanding energy supplies.

When two years after Mao's death the Chinese started to tell the world the truth about the country's affairs all the admissions reinforced a simple fact: China is a poor country, and most of its huge population lives barely above the basic subsistence level. Being such a big economy, its aggregate performance figures are large, some of them—including total energy output—ranking among the world's top five, but its per capita achievements are decidedly modest.

China's per capita GNP of around U.S. $ (1986) 400 puts the country just into the top third of the world's poorest group of nations (the World Bank's thirty-five or so low-income economies), some 30 percent ahead of India and roughly at par with Pakistan. Recently released income statistics show that historical disparities between rich coastal and poor interior provinces have actually intensified. By the late 1970s most Chinese ate no better than they had two decades before, a depressing stagnation reversed only through the recent de facto privatization of farming. Countless accounts in resuscitated professional journals have detailed widespread economic mismanagement and shocking production inefficiencies.

In the late 1970s, after three decades of impressive, although uneven, growth, China became the world's third largest producer and consumer of commercial energy. China's large population, however, shrinks this absolute accomplishment to a very modest relative figure of about 700 kg of coal equivalent energy (or 20 GJ) consumed annually per capita in 1985, still slightly below the consumption average for all developing nations and an order of magnitude below the rich world's use.

In annual per capita energy consumption China is ahead of such populous nations as India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh—yet far behind those countries that, from conditions not unlike China's a generation ago, have risen to, or beyond, the economic take-off stage. In Asia, South Korea and Malaysia are, of course, the best examples (even more successful Hong Kong and Singapore are peculiar city-states that should not be compared with true countries).

However, most Chinese (nearly four-fifths), like most Indians or Nigerians, are villagers, and their annual per capita energy consumption is just between 200 and 400 kg of coal equivalent. Most of this inadequate supply comes from traditional biomass sources; fossil fuels and electricity are used with low efficiencies in industrial production and, to a much lesser extent, by urban households.

Commonalities of Chinese energetics with those of other populous poor nations are thus obvious: a low-income society with a predominantly rural population, still heavily dependent on biomass and using inadequate amounts of fossil fuels and electricity in an inefficient manner to industrialize its economy.

Shanghai, China's foremost industrial center, consumes commercial energy at a level approaching per capita rates of poorer European Mediterranean countries (nearly 2 tons of coal equivalent) while peasants on the loess highlands of Shaanxi dig out tree roots and collect dung cakes to cook their thin gruels and heat their cave houses. China's domestic energy gaps are thus no less wide and no less common than those between the urban elites of Bombay, Lagos, or Rio and the subsistence peasants of Bihar, Kano, or Ceara, respectively.

But there are peculiarities. Since the Communist Party assumed control in 1949, China is the only large, populous poor nation that has guided its modernization by the quite rigid central planning of, until most recently, a decidedly Stalinist variety, and this strategy has had a profound effect on levels, modes, and efficiencies of energy extraction, transfers, and consumption.

The Stalinist obsession with heavy industries, an unusually high share of coal in primary energy consumption, an excessive promotion of inefficient small-scale enterprises, and the ubiquitous mismanagement characteristic of systems lacking personal responsibility have combined to set China apart as perhaps the world's most wasteful convertor of commercial fuels and electricity. On the other hand, this deficiency presents a huge potential for efficiency improvements and conservation so that a significant part of energy needed to drive China's modernization can come from the existing production.

The size of China's population—1.06 billion at the end of 1986, about 22 percent of the global total—and the inevitable gain of at least another quarter billion people during the next generation will make solution of the country's energy problems extraordinarily challenging, especially as the choices should not worsen the already much degraded environment and should harmonize with maintenance of the intensive agriculture needed to assure food self-sufficiency (after all, one-fifth of humankind can never rely on imports to secure its food).

Fortunately, China, unlike other large, poor nations—oil-rich Mexico excepting—is very well endowed with virtually every kind of energy resource and can thus confidently plan for long-term energy self-sufficiency. Yet a closer look at this impressive endowment reveals many limitations: a few absolute shortages, some qualitative and many distributional limits, and the omnipresent relative ceiling as the country's riches prorate to only a modest patrimony when divided among more than one billion people.

In addition to its recent tumultuous history and its unequaled population size, the third of the greatest Chinese peculiarities is the unprecedented experiment of the post-1978 years. Although it is just the latest of repeated efforts to reconcile the irreconcilable—a one-party bureaucracy running an enterprise system—and as such it could easily be dismissed as a doomed temporary aberration or extolled as an admirable quest, it is undeniable that the new policies have already improved the lives of hundreds of millions of Chinese to an extent that they would have considered impossible just a decade ago.

These changes have ranged from fundamental physical betterment (most significantly, average per capita food availability shot up to within less than 10 percent of the Japanese mean) to a much looser spiritual milieu (from prospering Buddhist temples to frequently daring writing), and they are all part of a grandiosely conceived dash to national prosperity. Modernization in one generation is undoubtedly more of a mobilizational slogan than a realistic possibility, but the rush is on—and its energy requirements, even with the best conceivable conservation, can be characterized only as stupendous.

Consequently, this book, after first describing the country's energy resources, appraises the existing production and consumption patterns (subdivided into the two disparate realms of rural and industrial-urban energetics) and presents a detailed review and assessment of the ways Chinese are proposing to provide the energy supply for an economy whose output is to quadruple in two decades.

Adherence to Communist ideology continues, but the traditional pursuit of fu qiang—wealth and power—has been asserting itself conspicuously since 1978. This book will enable a persevering reader to judge the possibilities and limits of energizing the grand visions of Chinese prosperity in the coming generation and beyond.

2 Resources: Riches and Poverty

China's large territory—more than 6 percent of the world's continental surface—may not in itself be a guarantee of substantial energy endowment, especially as far as fossil fuel deposits are concerned: Brazil's poor mineral fuel fortunes come obviously to mind, and India's relatively small and poor-quality coal deposits and rather meager oil reserves are yet another example of unfulfilled expectations. But a large territory increases greatly the probability of substantial altitudinal differences and voluminous water flows: both India and Brazil have huge hydroelectric potentials, and China, with the world's highest plateau in the Southwest and large eastward-flowing streams dropping toward the coastal lowlands, is unsurpassed worldwide, leaving behind even the USSR's immense hydroenergy resources.

But the great eras of sedimentary minerals did not bypass China either, and the recoverable resources in the country's extensive coal basins are rivaled only by those of the United States and the Soviet Union; moreover, the quality of China's northern coals is mostly outstanding. Hydrocarbon reserves have been so far much less impressive, although they have been sufficient to support annual crude-oil output large enough to place China among the top half-dozen producers worldwide. However, a major offshore search, underway since the late 1970s and so far without any sensational discoveries to its credit, will in time certainly amass significant new reserves, and the latest policies of allowing the experienced foreign oil companies to take part in onshore exploration will surely result in the development of new oil and gas fields. China's sedimentary basins are simply too numerous and too extensive for this not to happen. At the same time, only an ignorant analyst could now join those irresponsible promoters who a decade ago were presenting China as the future Oriental Saudi Arabia.

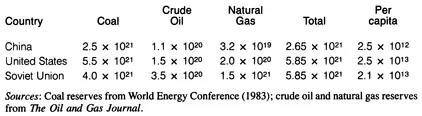

Table 2.1 Comparison of 1985 fossil fuel reserves in China, USA and USSR (all values are in J)

Even when leaving unequaled (but difficult to compare) hydro potential aside, superior coal deposits and substantial crude-oil reserves put China's mineral fuel reserves into the same order of magnitude as the United States and the Soviet Union, the world's two resource-richest nations (table 2.1). Yet, as the last column of table 2.1 shows, China's enviable energy patrimony shrinks to an order of magnitude below the U.S. or Soviet levels once divided by more than one billion people. This fundamental limitation brought on by the country's large population must be kept in mind when assessing China's modernization outlook. In per capita terms, China's fossil fuel reserves and hydroenergy potential are surpassed by dozens of countries, and although the known endowment is certainly large enough to energize the nationwide economic modernization and to allow for maintenance of a decent standard of life, it clearly sets major limits on the country's developmental strategy.

Even with the Japanese levels of energy conversion efficiency, the Chinese cannot contemplate achieving the levels of Western affluence of two generations ago. Increasing ownership of electronic gadgets, impressively improved life expectancy (especially in Asian comparisons), and better everyday diets are most welcome tangible signs of China's developmental success, but the great attributes of affluent Western civilization—cheap and varied food, comfortable housing, personal mobility, and easy access to higher education—are subsidized by energy flows averaging annually at least 60-80 GJ per capita, a level the Chinese simply cannot reach during the next two generations (as already noted, their current annual consumption averages about 20 GJ per capita).

The other notable complicating factors concerning China's modern energy resources are extremely uneven spatial distribution of coal reserves and a no less unbalanced location of the huge hydroelectric potential. And although among the alternative energy resources geothermal potential should eventually be of major local importance, opportunities for direct solar energy conversion are relatively limited, as is any modern, efficient conversion of biomass energies traditionally used in an inefficient manner throughout China's countryside.

Altogether, then, this is a story of dichotomies: absolute riches dissolved in relative poverty; development of large resources made difficult by staggering regional disparities; promising theoretical potentials negated by technical considerations. The following sections will document the main points made in this brief opening, first for the renewable flows, then for fossil fuels.

2.1 Renewable flows

One of the beneficial legacies of the heightened worldwide interest in energy affairs has been the emergence of a more systematic look at resource endowment. Before 1973, surveys of energy resources rarely went beyond fossil fuels, whereas after that great divide, inclusion of renewable capabilities appears to be obligatory even when the practically exploitable potential adds up to merely marginal contributions. Fortunately for the Chinese, theirs is not such a case: the country is endowed with impressive geothermal energy flows whose harnessing can translate into far from negligible local heat and electricity supplies; it has an abundance of slope land suitable for fuelwood plantations, which can make, with proper species selection and careful management, a fundamental and sustainable difference in easing severe shortages of heating and cooking fuels throughout rural China; and its hydroenergy potential, by far the largest in the world, can be tapped both in the form of tens of thousands of small hydro stations suitable for local electrification and in scores of multigigawatt projects, including several of the world's largest hydro sites whose development is planned to make a critical contribution to China's modernization effort.

The only major weakness in the renewable realm concerns direct solar radiation, whose flux is lowest in the most densely settled regions. Consequently, I shall start a review of the renewable flows with a rather brief look at this relatively marginal source and end it with a detailed appraisal of the rich hydroenergy capabilities.

2.1.1 Solar radiation and wind

China's first nationwide map of insolation became available in 1978 (fig. 2.1). It confirmed the expectations based on the country's location at the eastern fringe of the Eurasian landmass: solar radiation has a generally declining NW-SE gradient, with the peaks on the high Xizang-Qinghai Plateau and with the minimum in the southern interior basin and valley locations. This distribution, reflecting the pronounced influence of the Siberian anticyclone in the Northwest and the strong cyclonic (monsoonal) flows in the Southeast, makes for a nearly perfect mismatch between the total radiation received at the ground and population density. The peak values are on the virtually uninhabited Xizang (Tibetan) grasslands, and the minima embrace all of Sichuan, by far China's most populous province with over 100 million people. A newer map, published in the inaugural issue of a new solar energy journal (Wang, Anang, and Li 1980), differs in numerous details but displa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 CHINESE ENERGY: COMMONALITIES AND PECULIARITIES

- 2 RESOURCES: RICHES AND POVERTY

- 3 EXTRACTION AND UTILIZATION: TWO ECONOMIES

- 4 MODERNIZATION: ENERGY FOR THE QUADRUPLED ECONOMY

- 5 THE OUTLOOK: APPRAISING THE LIMITATIONS

- References

- Appendices

- Index