eBook - ePub

Medicine in the Remote and Rural North, 1800–2000

J T H Connor, Stephen Curtis, J T H Connor, Stephen Curtis

This is a test

Share book

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Medicine in the Remote and Rural North, 1800–2000

J T H Connor, Stephen Curtis, J T H Connor, Stephen Curtis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume of thirteen essays focuses on the health and treatment of the peoples of northern Europe and North America over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Medicine in the Remote and Rural North, 1800–2000 an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Medicine in the Remote and Rural North, 1800–2000 by J T H Connor, Stephen Curtis, J T H Connor, Stephen Curtis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire du monde. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I: Remote Medicine and the State

Introduction

The authors of this section illuminate some of the major challenges states confronted in their efforts to provide medical care in remote areas. One problem was to attract and retain skilled medical practitioners willing to work in such isolated and physically demanding surroundings. Government officials also found it difficult to maximize the medical benefits they could offer while keeping costs firmly under control. This certainly was no easy feat when a small population was dispersed widely over a hostile environment. A sense of suspicion, both on the part of the medical practitioners and the intended recipients of medical innovations further complicated the efforts to introduce a more uniform level of medical care. Those living in the northern-western province of Russia that Steven Cherry and Francis King discuss were particularly reluctant to accept medical ‘outsiders’ and this was a major obstacle to the spread of academic medicine. Taken together, the contributions by Teemu Ryymin and Astri Andresen reveal a long history of state involvement in the provision of medicine to the Sami. During the course of the twentieth century the Norwegian government gradually abandoned its efforts to impose its perception of medical ‘improvements’ upon those living in the far north. Instead, it launched a comprehensive medical initiative particularly during the second half of the century that consisted of large financial expenditures and a new-found respect for Sami culture. This coincided with international movements whose mandates were to preserve and acknowledge the importance of indigenous cultures. To that end, newly trained Sami doctors are now able to provide their patients with modern and traditional medicines. The major challenge facing government health officials in twentieth-century Scotland was largely logistical rather than cultural, but tensions existed even within this homogeneous population. Marguerite Dupree’s analysis demonstrates that although the Scottish government introduced a much more rational and streamlined form of medical care than had ever existed, local residents frequently questioned whether the organization of the HIMS provided the best possible solution to their medical needs. Their input helped inform the legislation that finally emerged.

The contributions to this section reveal that attempts to introduce cost-effective medical systems was as much a challenge to the Russian authorities of the late nineteenth to early twentieth century as they were to Scottish and Norwegian authorities even in the late 1990s. In each case the success of central governments depended upon their ability to adopt policies that would enable them to overcome logistical problems while simultaneously minimizing sources of cultural tension. Some of these movements were motivated and directed entirely by domestic concerns but Ryymin and Andresen show that international forces eventually influenced medical legislation that emerged in Norway during the second half of the twentieth century.

1

Medical Services in a Northern Russian Province, 1864–1917

Russian zemstvo medicine is a purely social matter. Treatment by a doctor in the zemstvo is not a personal service to the patient at his expense, nor is it an act of charity. It is a social service.

M. Ia. Kapustin2

This paper investigates the organization of medical services under extreme conditions, in some northerly parts of European Russia during the era of zemstvo reform: the period of rural self-government that existed between 1864 and 1917. It concentrates on the north-western guberniya (province) of Olonets, now largely part of the Republic of Karelia.3 An area characterized by its remoteness, relatively harsh geographic and climatic conditions and meagre economic resources from which to finance medical services, Olonets was also perceived as ‘culturally backward’. Its inhabitants were often suspicious of or antagonistic towards outside influences, whether in the form of governmental authorities or would-be improvers in health, hygiene and medicine. Arguably, the reluctance of health-care professionals to work in such an environment aggravated matters, although there were also distinct attractions in practising zemstvo medicine. Given such contexts, the study has relevance to suggested ‘core and periphery’ and ‘distance decay’ issues (see the introduction to this volume) affecting health care provision in remote areas.

The wretchedness of Russian peasant life in the late nineteenth century, readily apparent to contemporary observers, has also been a reoccurring theme for modern historians.4 Russia’s northern provinces posed particular difficulties, as each contained uezds or districts,’ that were remote and barren, lying on or within the Arctic Circle. The northernmost province of Arkhangel included the strategically important ports of Murmansk and Arkhangel’sk but was otherwise very sparsely populated. With much of economic activity featuring the seasonal migration of reindeer and the nomadic Sami herders, the zemstvo reform of 1864, whose system of local government depended on settled communities, was not extended to Arkhangel guberniya. The provinces of Vologda and Perm’ also had very sparsely populated northern uezds, though their southern districts were considerably more developed. Olonets was thus the most northernmost province included within the zemstvo reform. A wholly rural and sparsely populated area, it featured a harsh climate with average temperatures hovering around freezing point.5 The local provision of rudimentary – but largely free – health care therefore occurred under extreme conditions, yet shared the characteristics of the emergent zemstvo medical system as it was implemented throughout European Russia.6

Early Health Measures and the Zemstvo System

During the eighteenth century, Russia’s size, poverty and alleged ‘backwardness’ constituted formidable barriers to the erratic and top-downwards modernization of the body politic. Measures to promote commerce, business and the professions using controlled electoral procedures and the granting of charters to towns and nobility also produced local leaderships concerned with public health, morality and limited philanthropic effort.7 By the early nineteenth century, the Ministry of the Interior assumed some responsibility for public health, conventionally depicted as ‘hampered by extreme shortage of medical personnel and medical stores, both of which were still further reduced by the demands of the army … the hostility of the peasants and the indifference of the educated classes’.8

Medical qualification, licensing and regulation were state controlled. Amongst the 8,000 physicians practising in 1845, the degree-qualified and licensed vrach were outnumbered by lekar with their basic, five years’ training.9 Physicians might harbour professional and even political reform agendas but their official status and functions in sanitary policing, dissection, hospitalization and the supervision or monitoring of local healers led district populations to identify them with state authority.

Although health measures, private practice and medical personnel were concentrated on St Petersburg and Moscow, several agencies offered patchy and rudimentary provincial services. Prikaz (Office of Public Welfare) provision, largely uncoordinated and urban, included some 500 provincial hospitals with almost 19,000 beds by the early 1860s. Provincial and district public health committees, established from 1845 onwards, monitored epidemics to little immediate effect and, like the provincial hospitals, had a poor reputation with the peasantry. Since the 1820s the Ministry of Appanages had provided physicians and feldshers (semi-trained health workers) for ‘court’ peasants in the service of the imperial family, and the Ministry of State Domains made similar arrangements for peasants on state lands. During the 1850s this constituted a rural system of sorts, and by 1867 some 350 physicians provided training and supervision for roughly 5,500 feldshers who were mainly responsible for outpatient clinics and domiciliary visits.10 Meanwhile, the number of village pharmacies had tripled between 1827 and 1852, by which time there were 1,200 in operation, along with some 250 lechebnitsy (local clinics) reportedly attracting increased peasant attendances.11

Defeat in the Crimean War in 1856 emphasized Russia’s need of modernization and reform, seen in the emancipation of the peasantry from 1861 and the establishment of the zemstvo system in 1864. This system, consisting of locally elected assemblies based on a restricted, property-owning franchise, offered a degree of self-government in thirty-four guberniyas of European Russia. In addition to the provincial assemblies, zemstvos were simultaneously created for district subdivisions. The Ministry of Internal Affairs retained its own ‘reach’ into the countryside but the zemstvos were granted powers of local taxation and greater responsibilities, notably for education and public health. ‘Improvement’ in these areas had no specific form or agency, however, and the position of the zemstvo was ambiguous: conceived as part of state power and a source of expertise, they were potentially also a forum for opposition and professional interest, as seen in the development of health care.12

The zemstvos inherited limited guberniya-level health facilities and hospitals, although those at the uezd level barely existed and more remote areas were completely devoid of trained medical practitioners. With no template to shape its emergence, the ‘zemstvo system’ of health care was piecemeal but innovatory and acclaimed by its supporters. Thus A. A. Sinitsyn, an early zemstvo physician recalled, ‘nowhere in the West did we have any precedents for this, and in Russia up to that time nothing had been done in this direction: therefore, we had to start from scratch, not having any models for guidance’.13 The system was characterized by its devolved organizational forms, an emphasis upon public hygiene and preventive medicine as well as treatments, and the promotion of modern medical care not conditional upon the payment of fees to physicians.14 Another strongly influential but sometimes constraining feature was the emphasis on ‘fairness’; the ambition that medical service provision should be equally accessible to all inhabitants, wherever they lived. In 1894, the Entsiklopedicheskii slovar described zemstvo medicine as ‘the pride and glory of the zemstvos, Russia’s unique contribution to public health, developed without previous example in the West and adapted especially to Russian needs’.15 However, the historian and leading contemporary authority Boris Veselovsky also noted uneven or delayed developments in many areas, particularly in the deployment of public health measures and the organization of guberniya-level doctors’ congresses.16

Veselovsky’s observations are relevant to the situation in the province of Olonets guberniya, where the delivery of medical services to a scattered, poverty-stricken population provided a daunting challenge. Three-quarters of the province’s 150,000 km2 – an area the size of England and Wales – were covered by forests and lakes, the latter aiding communications during the short summer. A limited growing season vulnerable to unreliable weather and poor quality soils in all but the southernmost districts meant that agriculture was underdeveloped. Serf-owning landlordism had hardly featured in most areas prior to emancipation, and peasants on former state lands practised subsistence farming, often using slash-and-burn methods because there was insufficient open ground or livestock to manure the soil.17 Agricultural productivity remained low, and although hunting, logging and fishing were vital supplementary activities, the province was still a net importer of foodstuffs in the twentieth century.18

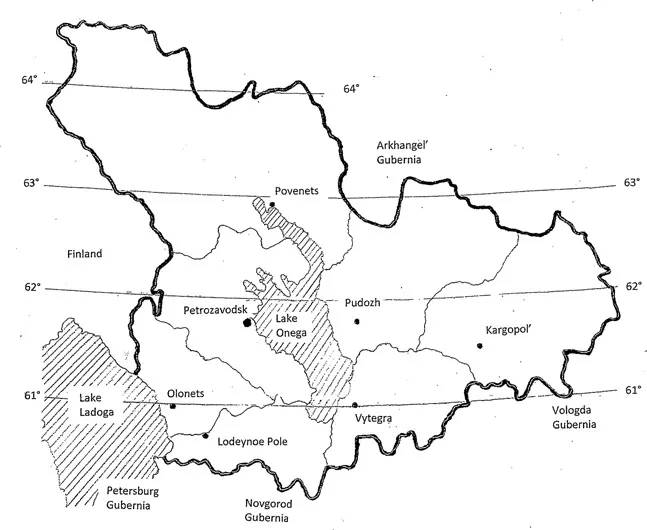

Figure 1.1 Map of Olonets guberniya and uezd towns, Russia.

The Olonets guberniya was divided into seven uezds: Petrozavodsk, Olonets, Vytegra, Kargopol’, Lodeynoe Pole, Povenets and Pudozh. Each of these were named after principal towns which were mainly marketing or administrative centres but essentially agglomerated village settlements. Rural peasants still comprised 92 per cent of the provincial population in 1913, with just 4 per cent regarded as ‘townsfolk’. One half of the latter lived in Petrozavodsk, from 1781 the guberniya ‘capital’ and easily the largest town with 10,961 people in 1868 and 18,878 by 1913. Olonets town was more typical of the remainder of the villages; its 1913 population was just 2,095.19 Generally the provincial inhabitants were dispersed, numbering barely 300,000 in 1867, 368,000 at the 1897 census and over 425,000 in 1913, when 78 per cent were Russian, 16 per cent Karelian and 4 per cent Estonian.20 Logging, which employed roughly 3,000 people, and iron-working, developed from mining and works begun under Peter the Great before 1714, were the principal industries. There was no railway...