1

NAVIGATING PRECARIOUS TERRITORY

Teaching Turkish in Greek-Cypriot Classrooms

Panayiota Charalambous, Constadina Charalambous and Ben Rampton

Introduction

While conflict certainly features in discussions of language teaching and intercultural communication, the intensity of conflict generally falls short of violent warfare (MacDonald and O’Regan 2012: 560). Indeed, after working in Gaza, Phipps suggests that a notion like “intercultural dialogue in its present dominant manifestation has run its course”, unable to engage with questions like: “How do we teach people to think and to act under emergency conditions and to prepare for life in such situations? How do we get beyond an ethic of dialogic ‘balance’ or ‘neutrality’ in conditions of precarity and insecurity?” (2014: 120). More generally, she suggests, “concepts which have arisen in contexts of relative peace and stability in Europe are not suited to conditions of conflict and siege” (2014: 113).

In fact, contemporary literature on language teaching in contexts of recent conflict does raise questions about the adequacy of prevailing ideas about intercultural language education. The present chapter seeks to contribute to this literature by focusing on Turkish language teaching in Greek-Cypriot schools and adult institutes. In 2003, in the midst of the EU Accession process, the Republic of Cyprus introduced Turkish classes for Greek-Cypriots as a gesture of goodwill towards Turkish-Cypriots, after a long period of intense hostility. But students who opted to enrol were routinely accused by their peers of being ‘traitors’, and teachers developed a number of practices to circumvent the intense controversy that surrounded Turkish language learning. Against a background of this kind, the dynamics of familiar pedagogies such as ‘grammar and translation’ and ‘communicative language teaching’ look rather different, and in this chapter, we describe three different approaches used by Greek-Cypriots teaching the language of the (former) enemy, glancing sideways at the discrepancies that emerge when we set them next to European language teaching orthodoxies. In addition, of course, acute hostility and a sense of physical threat can take different forms, affected by geo-political specifics. So it is also important to try to specify the type of precarity and insecurity involved in teaching Turkish to Greek-Cypriots, and for this, we draw on research in International Relations on ‘securitisation’.

We begin with a sketch of securitisation theory and identify several different contexts in which language teaching is substantially affected by heightened insecurity. With this rudimentary outline in place, we then describe the grounds for seeing these Turkish classes as part of a larger-scale de-securitisation process. After that, we move to our ethnography of different approaches, pulling out their heterodox implications for language teaching theory, and we conclude by noting the specific affordances of language learning as resource in peace education.

Securitisation as a Perspective on Language Education

‘Securitisation’, a notion initially associated with the ‘Copenhagen School’ of security studies (Buzan and Wæver 2003; Emmers 2013), refers to institutional processes in which threats to the very existence of the state and other bodies are identified, and in response to this potential danger, issues are moved from the realm of ordinary politics into the realm of exceptional measures, where normal political rights and procedures are suspended. Throughout this process, discourse plays a crucial part, both in declaring a particular group, phenomenon or process to be an existential threat, and in persuading people that this warrants the introduction of special measures. While earlier formulations of securitisation theory relied heavily on Austin and Searl’s speech act theory, this limited model of communication has been extensively criticised (e.g., Stritzel 2007), and more recent work offers a more sociological and pragmatic account, with references, e.g., to Sapir, Goffman, Schegloff, Wetherell, Duranti and Goodwin (Balzacq 2011). Securitisation theory, in other words, has undergone something of a sociolinguistic and linguistic anthropological ‘turn’, and although “insights drawn from ethnographic research have not been systematically brought to bear” (Goldstein 2010: 488), the pieces certainly seem to be in place for some linguistic ethnographies of securitisation.

If we turn now to language education, insecurity and warfare have always been very significant influences. Howatt’s A History of English Language Teaching starts with sixteenth-century Huguenots arriving as refugees from the counter-reformation (1984: Ch.2), and in the 1940s, the very term ‘applied linguistics’ sprung from the marriage of Bloomfield’s structuralism with language training in the American army (1984: 265–9; also e.g., Kramsch 2005). Yet detailed descriptions of security-oriented language pedagogy are relatively rare, and below we offer four rather different contexts in which security concerns have been prominent in relation to language teaching.

First, Uhlmann’s (2010, 2011) rich anthropological account analyses the teaching of Arabic in Israel, where long-standing security perspectives dominate Arabic pedagogy, and military intelligence plays a central role, as curricular activity largely “revolves around preparing Jewish [secondary] students for their impending military service” (2010: 297, 2011; also e.g., Mendel 2014). When comparing Arabic instruction to the much more creative and communicative teaching of English in Israel, Uhlmann speaks of the ‘Latinisation’ of Arabic, approached “as if it were a dead language like Latin, to be interpreted and understood but not necessarily creatively engaged with and idiomatically used” (2011: 100). As he explains, this has been “the result of different stakeholders….—namely the security apparatus, teachers, and universities—pursuing their own specific interests in this field” (2011: 101). So there is much more involved here than out-dated, old-fashioned pedagogies.

The second example turns the focus to processes of increasing securitisation and ‘generalised suspicion’ in everyday institutional life (Huysman 2014). Khan’s (2014) account of British public discourse from 2001 to 2014 traces the ways in which English language teaching for adult immigrants is increasingly becoming a matter of national security, focusing on the introduction of language tests for citizenship as an instance of ‘exceptional securitisation’ following fast on urban riots in 2001. But beyond that, he argues that this commitment to special measures has permeated to other entry and settlement requirements and may be affecting English language education as well.

In the third situation where security concerns affect language education, the processes described by Khan are reversed. In de-securitisation, issues, groups and processes are moved out of special measures back into the realm of ordinary political and civil affairs. In the Cypriot case described in the next section, the state introduced Turkish language teaching as a policy instrument during intense negotiations aimed at reunification of the island. With the onus on drawing closer, this might sound like a classic instance where intercultural language orthodoxies move to the fore, but even in this situation, ‘Latinisation’ may sometimes seem the best way forward, as we shall shortly see.

Last and more locally, acute insecurity can influence language pedagogy in classes for migrants and their children, regardless of the level of securitisation in the host/receiving country itself. This is made clear in Karrebæk and Ghandchi’s (2014) interactional ethnography of a Farsi language school for children and adolescents of Iranian descent in Copenhagen. Here, the dominant pedagogy again focused overwhelmingly on grammar and vocabulary, deliberately avoiding references to contemporary Iranian culture, but in this case, the purpose was to exclude anything that risked invoking and inflaming acute political divisions within the Danish Iranian community. In fact in many language classes with refugees from conflict zones, teachers are likely to respond in a broadly comparable way to their students’ legacies of insecurity, regardless of political relations in the host country at large (e.g., Cooke and Simpson 2008: 37).

Although these four situations should not be construed as a rigorous matrix for extrapolating different empirical possibilities (cf. Liddicoat 2008: 130), the list does indicate a plurality of situations where precarity may destabilise ideas about language pedagogy formulated in peace and stability, and where standard proposals about putting culture at the heart of language teaching could sound risky, ineffective and even culturally insensitive. We should now turn to the more detailed empirical investigation of just one of the contexts where violent conflict affects language teaching.

Cyprus: From War and Partition to De-securitisation

Turks have been viewed as a threat in Greek-Cypriot society since the advent of Greek and Turkish nationalist ideas on the island towards the beginning of the twentieth century (e.g., Bryant 2004). In the 1950s and the 1960s, there was an escalation of interethnic violence between the Greek-Cypriots and Turkish-Cypriots, and subsequently, the 1974 war had devastating consequences, leaving the island de facto divided. Since then, Greek-Cypriots and Turkish-Cypriots have been forcibly relocated into the south (government-controlled areas) and north of the island (occupied areas), respectively. With a suspension of all communication until 2003, this physical and cultural division has consolidated the two communities’ ‘ethnic estrangement’ (Bryant 2004: part 4).

Despite the lack of recent violence in Greek-Cypriot society, the representation of Turks as the primary national ‘Other’ and as a security threat has been institutionalised, and hostility-perpetuating routines have been well documented in the media and public discussion (Adamides 2014), as well as in education (P. Charalambous 2010; Zembylas et al. 2016). Turks have also been constructed as a security threat in educational discourse, both in and out of class (C. Charalambous 2012; Papadakis 2008). Spyrou’s (2002) anthropological research showed that Greek-Cypriot children see Turks as the principal ethnic ‘Other’, while research in peace education initiatives reveals that these representations are usually associated with taught collective emotions of fear, trauma and anger (P. Charalambous 2010; Zembylas et al. 2016).

However, hopes for a final settlement increased in 2003; as the Republic of Cyprus signed the accession to the European Union, negotiations intensified over the prospect of the island’s reunification, and the Turkish-Cypriot authorities decided to partially lift restrictions of movement across the buffer zone in Nicosia, permitting access between north and south for the first time for almost 30 years. In response, the (Greek-) Cypriot government announced a package of measures ‘for Support to Turkish-Cypriots’ – also often referred to as ‘Measures for Building Trust’. As well as issuing passports and certificates and allowing Turkish-Cypriot citizens access to civic and welfare provisions, the package declared that Turkish language classes would be established in Greek-Cypriot public education: Turkish would be one of the Modern Foreign Language options for secondary school students and available free in afternoon classes for adults.

This package of measures can be viewed as a key desecuritising act (Buzan et al. 1998; Wæver 1995), seeking to move Turkish-Cypriots from a state of exception and to reintegrate them into ordinary civil society. Within this, setting up Turkish classes can be seen as an emblematic gesture that endorses Turkish as an official language of the Republic, and as – in Balzacq’s later formulation – a ‘policy tool’ to help normalise inter-communal relations (2011: 16; see also Rampton and Charalambous 2012). However, just as with acts that securitise, de-securitising initiatives need to persuade their audience if they are to be successful. In situations like Cyprus where intense hostility has been routinised and institutionalised (Adamides 2014), attempts to de-securitise can be often perceived as threatening, themselves provoking widespread enmity and suspicion (see also the fierce reactions to the peace education initiative introduced in 2008, Zembylas et al. 2016). In what follows, we investigate precisely this dynamic: Turkish teachers’ commitment to enact this de-securitisation policy, the resistance of many students socialised into Hellenocentric thinking, and teachers’ practices to overcome this tension. But before describing our findings, we must first outline the overall empirical projects.

Two Linguistic Ethnographies of Turkish Language Learning

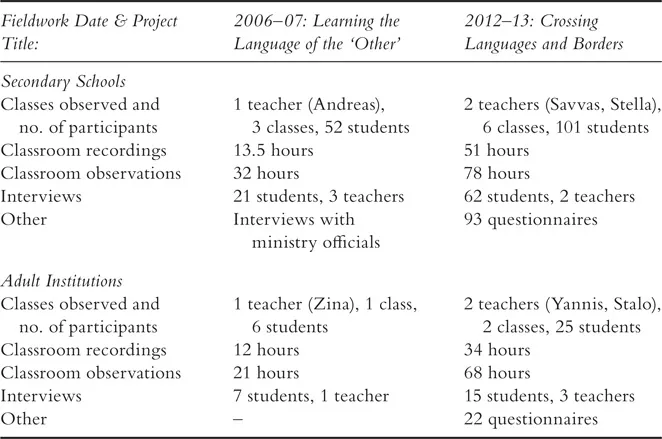

Our data derive from two studies looking at Turkish language learning in Greek-Cypriot secondary schools and adult afternoon classes. The first was a doctoral study titled Learning the Language of ‘the Other’, funded by King’s College London (C. Charalambous 2009), and the second was a project funded by the Leverhulme Trust (2012–15) titled Crossing Languages and Borders: Intercultural Language Education in a Conflict-troubled Context. In the first – henceforth the ‘2006’ study – fieldwork took place in 2006–07, close to the initial introduction of Turkish language classes, while in the second (the ‘2012’ research), data were collected almost a decade after Turkish officially started in Greek-Cypriot secondary education. The secondary students in both projects were 16–17 year olds, while the adult learners were aged between 25 and 70. Both projects were designed as linguistic ethnographies (Rampton 2007), combining analysis of interviews and classroom discourse with consideration of historical, socio-political and institutional dynamics. Methodologically, the 2012 study was designed along similar lines to the 2006 project (see C. Charalambous 2009, 2012), aiming to map both the continuities and the shifts observed since 2006 across different educational settings. During the 2012 project, data analysis involved twenty-four months of data processing, it was assisted by NVivo9 and produced twenty thematic reports in total, involving, amongst other things, descriptions of the wider institutional culture; ethnographic descriptions of classroom practices and interactional analyses of selected episodes; comparisons of discourses and practices in adolescent and adult classes; thematic analyses of participants’ interview accounts; and an analysis of a short survey questionnaire. Table 1.1 provides a summary of the two datasets.

TABLE 1.1 Overview of the Dataset

So what did all this reveal about language teaching and learning within the contested process of de-securitisation? It is worth beginning the account with...