eBook - ePub

Reframing the Leadership Landscape

Creating a Culture of Collaboration

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In an uncertain and complex world leaders should not merely respond to the speed of change but attempt to anticipate it. Sometimes it is unexpected, sometimes the signs are there but the dots are not joined together. The NEW normal must be navigated, negotiated, networked and a narrative built around it. Leaders need to adapt to a changing ecosystem in which the biggest challenges cross the boundaries of the public, private and non-profit sectors, requiring much closer collaboration. Aggressive individualism is no longer a sustainable basis for companies needing to deliver social and economic value, now, enterprises must move beyond narrow self-interest and short-termism to balance stakeholder expectations. In Reframing the Leadership Landscape, Dr Roger Hayes and Dr Reginald Watts argue that the interconnected and interdependent world requires leaders to adopt a more holistic and inclusive approach. Despite global business education advances, business mostly fails to make cross-disciplinary connections or interpret weak signals and is ill-prepared for changes in cultural and technical demands. The tool kit is here, ready to be unpacked. The only question is whether aspirant leaders are sensitive enough to read the signals and develop the skills needed to create an essential collaborative paradigm, which they must do if they wish to regain trust, fill the leadership void and help reshape a sustainable future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reframing the Leadership Landscape by Roger Hayes,Reginald Watts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

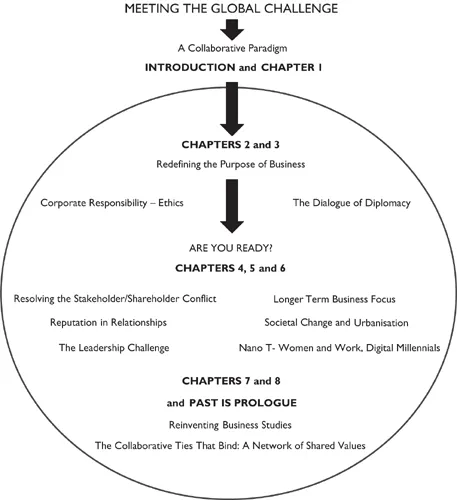

PART I

Meeting the Global Challenge:

A Collaborative Paradigm

Introduction

In an uncertain and complex world leaders should not merely respond to the speed of change but attempt to anticipate change. Sometimes it is unexpected, sometimes the signs are there, but the dots are not joined together. Many senior executives are disconnected from the environment around them – too busy, too focused, too inward looking, developing strategies based on past experience. More usually leaders blunder on trying to continue as before in the hope that things will soon be back to normal. Couple the collusion of global forces with the convergence of economics, politics and culture, there is no normal. The new normal must be navigated, negotiated, networked and a narrative built around it. There will be as much collaboration as competition, a greater need to listen, learn, link and lead. Are you ready?

Change is multi-faceted and if, for example, the economy swings back, social change has moved on, with digital communications taking up the slack or pressure groups becoming more demanding, invalidating existing operating models. Customers are also citizens. Some shareholders take a long-term view. Economists worry about capital markets, but ignore social disruptions. Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) have negative visions of capitalism and Internet geeks argue for a world united by the Web. In ‘A Future Perfect: The Challenge and Hidden Promise of Globalisation’ (2000) Mickelthwait and Wooldridge wrote: ‘Business people often know the meat and bones of the subject (of globalisation) better than anyone else does – the companies and products that are drawing the world together – but they are too wrapped up in the struggle for profits to consider the wider picture.’ Future leaders will need multidimensional thinking, operating in multiple timeframes, and the ability to connect unconnected disciplines and be prepared for continuous learning.

In the new era, centres of economic activity will shift dramatically, not just globally, but regionally. The consumer landscapes in India, China, Brazil and Africa are expanding significantly, with massive cultural implications. Technological change has become a cliché, but equally important is behaviour changing, people forming relationships in ways unforeseen. Cities will become as important as countries, forming new kinds of communities, not just Mumbai, Dubai and Shanghai, according to McKinsey & Co.,(2013/14) but Porto Allegro, Brazil, Kumasi, Ghana and Tianjin, China. Snippets of information, often hidden in social media streams, offer leaders a valuable new tool for staying ahead, so long as senior leaders are sensitive to these ‘weak signals’.

The role of business will come under even more scrutiny as will that of government. Both need to adapt to a changing ecosystem in which the biggest challenges cross the boundaries of the public, private and non-profit sectors, requiring much closer collaboration. Just as governments have an opportunity to figure out how all stakeholders should work together on an issue or in a sector, so too do corporations need to move beyond narrow self-interest and short-termism to balance stakeholder expectations. In large and unequal newly emerging economic powerhouses like Brazil, India and Indonesia, the forms of capitalism that privilege private wealth creation and shareholder value above all, are ultimately incompatible with democratic politics. The growing level of concentration of capital experienced now in the more advanced countries where the middle classes are being squeezed is unsustainable and could eventually lead to a political backlash. The level of house prices in Singapore and London are classic examples of tension. The smarter enterprise has the potential to create sustainable economic and societal growth. But this will require new ways of working, new mind-sets.

The purpose of the book therefore is to identify and join up the signals of change in an interdependent, interconnected and intercultural world, define what qualities will be needed by heads of organisations in business, government, global charities or within the tidal wave of NGOs strewn across the world and establish a model, particularly for business organisations and the higher education system that feeds them. The tool-kit is there ready to be unpacked. The only question is whether ambitious managers aiming for the sky are sensitive enough to read those signals and develop the ambidextrous skills to lead so as to help create a collaborative paradigm within and between organisations and the global system.

The collaborative paradigm requires of business and other leaders an understanding of:

1. The convergence of business, government, civil society/ public opinion.

2. The interdependence of the global environment, countries, cities and communities.

3. Balancing self with societal interest.

4. Understanding the link between rational and emotional.

5. Adopting an interdisciplinary approach to concepts and fields of study.

6. Eroding barriers between countries, institutions and departments.

7. The interaction of theory and practice.

8. Co-creating and engaging with, often uncomfortable stakeholders.

9. Being critical of overly ‘Western-centric’ interpretations, including short-termism.

10. Replacing a command and control mentality with one of conversation and collaboration.

As former United Nations (UN) Secretary–General Dag Hammarskjold was fond of saying – setting the bar higher than was thought possible, then having scaled it, realising it was too low.

Chapter 1

‘Google Glasses’: Reframing the Leadership Landscape

Different chapters serve to deliver goods to various destinations with diverse outcomes, attempting to attract different stakeholder communities to the central theme of leading for stakeholder value via a collaborative paradigm, a relational approach, creating value together. The relationship is the last driver of sustainable value. To identify the key issues and develop the trust to build coalitions and form partnerships means building relationships, requiring dialogue and diplomacy skills that will be picked apart later in the book. This chapter discusses not just global challenges but also opportunities, which can help governments, corporations and other institutions distinguish themselves and their organisations. The conditions are that the world has been turned upside down. The context is one of no place to hide, combined with a decline of deference with less trust in institutions and their leaders than ever before. The consequences are momentous for business, government and civil society whether in the emerging world or the traditional, advanced economies. To be sustainable means combining economic with social value. This in turn demands a stakeholder approach predicated on the emergence of new kinds of leaders. It is safe to assume that what got us here won’t get us there. Einstein was right when observing that you can’t solve a problem with the same mind-set that created it. Whereas financial capital supported physical capital in earlier ages, in a globalised world characterised by interconnectedness and interdependence, change and complexity, social capital has become vital currency. Such capital requires networking, negotiating, navigation and narrative skills as never before and a completely new mind-set.

Countries, corporations and civil society are converged. Singapore is a city as well as a state, largely comprising multinational corporations. Companies are competing against countries, often via their sovereign wealth funds. The European Union (EU) is a ‘network’ of states, London is effectively a city–state economically distinct from the United Kingdom (UK). Mayors from China to the United States (US) are working with business from the ground up, not top-down, involving local individuals and organisations, and in the process forming new kinds of communities. We are living with informational capitalism and strong profit seeking, often at the cost of soul searching. This is much needed when, despite the growth of middle classes from China to India, poverty and social exclusion lurk not far away, or in the case of Rio de Janeiro and Mumbai, right next door. Living in a global neighbourhood, these issues are everyone’s business. It is not a question of the state versus the free-market, but closer collaboration between business, government and civil societies in creating and maintaining communities. To achieve those will require far greater business and broader leadership. But what are the essential elements leaders need and the context – cultural, political and economic – within which it operates? This book will attempt to provide an answer to that question.

The Diffusion of Power

Globalisation and the information, communications and telecommunications revolution has gone to a whole new level, from connected to hyper-connected. Tom Friedman (2005), the New York Times columnist, who coined the term ‘flat’ to describe the shape of the new world believes this means we all have to study harder, work smarter and adapt quicker than ever before. So yes – we have to learn to manage complexity and deal with connected capitalism by creating smarter enterprises. What’s more, this same phenomenon enables the ‘globalisation of anger’, super-empowering individuals to challenge hierarchies and traditional authority figures as never before, from government and business to science and religion. This phenomenon is making governing, managing and influencing harder, hence the need for a new kind of leadership. Effectively the pyramid of power has been turned upside down. As CNN’s Fareed Zakaria (2008) put it: ‘Power is shifting away from nation states up, down and sideways.’ More and more ‘actors’, starting with environmental NGOs and, more recently, multinational corporations, 24/7 TV news and now ‘citizen journalists’ and ‘civil society activists’, are taking to the global political stage. Anand Mahindra, Chairman of Mahindra Group, noted the 28 elected States of India (some larger than many countries) and the new cities created will be catalysts for India’s growth, emanating from an urban middle class whose interests transcend culture. This could enable India to pick up the slack from a slowing China. Michael Bloomberg, former Mayor of New York, argues that because cities are closest to the majority of the world’s people, they are better able than nations to get things fixed. London’s Mayor, Boris Johnson, would no doubt echo that sentiment.

We know that power is shifting from West to East, hierarchical organisations to lateral ones, even from dictatorships to protest movements. As Moises Naim, former journalist and Venezuelan Minister wrote (2013): ‘Power is easier to get, harder to use and easier to lose … the decay of power is changing the world’. Previous Heads of State and chief executive officers (CEOs) of large corporations, not to mention other institutions such as the Catholic Church, dealt with fewer challenges, competitors and constraints, such as media scrutiny, global cultural clashes and citizen activism than is the case these days. A photograph of Charles de Gaulle surrounded by his officials while commanding their absolute attention serves as a metaphor for an old style of leadership that no longer works. Compared to a Churchill, the status and credibility of Prime Ministers today is much diminished. Part of the reason must be over-exposure, but one of the keys then was they had experience of battle. Steve Jobs partly became a leader because he had actually designed the first Apple computer in his garage. New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani became a leadership role model because he had led New York so effectively at a challenging moment. As the British monarchy has found over recent years, the mystique has been lost, with barriers to entry falling. So Prime Ministers and CEOs now have to compete with celebrities and dissidents for attention, not to mention mayors.

Despite the different reasons behind recent protests, violent clashes from Russia to Turkey, Brazil to Egypt, Hong Kong to Malaysia, Bahrain to India, Greece to Spain – just as in 1848, 1968 and 1989 when people also found ‘a collective voice’ – they have much in common. It is interesting that protests have been as active in democracies as dictatorships – that it is largely ordinary, middle-class people condemning the alleged corruption, inefficiency and arrogance of the ‘folks’ in charge, or in some instances simply the alienation and detachment from the centre, recently observed in the UK, France and Spain. The Turkish Prime Minister even explicitly blamed ‘a menace called Twitter’ for the June 2013 Istanbul riots and has tried to ban all social media; a bit like trying to contain a breached dam. If it is now harder to govern, it is easier to refuse to be governed. Even in dictatorships we consent to be ruled. The reason is that the fear has gone, because we are not alone. A concern is that some media spreads information so fast that the organisational core becomes swamped and the agenda blurred. This makes it difficult to resolve conflict. Yet as unemployment and inequalities soar and the emerging world witnesses the political expectations of a rapidly growing middle class, it has become even more important for political, business and civil society leaders to anticipate and reconcile some of these conflicting interests.

Where are the Leaders?

Yet, just at a time when heads of institutions should be at the top of their game, they are falling short. In the UK, when traditional politics was becoming corroded by the reasons and results of the Iraq war and citizens were seeking alternative voices, where were the leaders of civil society, such as The Church of England? They were locked in internal squabbles, communicating in a manner more akin to a monastery than a public square. (At least the relatively new Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, combining a business and political background, has called for ‘a revolution’ in his church.)

Erik Schmidt of Google fame has argued that revolutions are easier to start than finish, with greater connectivity involving the young. This leads to more protests, full regime change or reform hampered by ‘a lack of sustainable leaders and savvier state responses’. Sometimes, as in the case of the 2011 London riots sparked by a police killing, the results were marked by lawlessness. The Occupy Movement, which protested in Sydney, London and New York against income disparities between bankers and ordinary people were more restrained in their protests by camping outside symbolic buildings. UK Uncut, however, raised the issue of tax avoidance among multinational corporations such as Vodafone and Starbucks. This led to politicians taking up this issue as a legitimate grievance, resulting in a grilling in parliament of their hapless executives. The Chairman of Christian Aid spoke out that financial secrecy works against human dignity, so multinational corporations should pay proper taxes in less-developed countries where they operate. This is a good example of the interconnectedness being discussed in this book and the interdependence between business, politics and public opinion. The tragic ferry disaster in South Korea and the disappearance of the Malaysian aircraft in 2014 are other examples of organisational and human-siloed thinking.

Convergence

Just as power has become more diffuse, so too, according to Mickelthwait and Wooldridge (2000), has ‘the internet fused media, politics and economics to the point where it is impossible to change one of these areas without impacting the other’.

Trade trumps missiles in today’s global power plays with traditional international politics being overtaken by economic diplomacy. This refers to the changing balance between the advanced and rising states in various trade negotiations and the risk of competing blocs, rather than open global arrangements. Following a decade of rapid growth, large swathes of Africa are going digital, particularly the cities. There are more African democracies than hitherto. Yet poverty remains stubbornly high. In South Africa, a first world economy lives next door to grinding poverty, which a broader capitalism collaborating with government and civil society could do much to avert. This is thanks to significant infrastructure investment, combined with low-cost smart phones and tablets enabling millions to connect. It will have a major impact on governance, agriculture, retail, health-care, education and financial services.

Creating Shared Value

So where might the future with its never-before-seen challenges and opportunities take us? Ericsson, a Swedish high-tech firm, believes in sharing knowledge about the future: ‘If we do, the future might not be a place we are going, but a place we create’ (Ericsson, 2013). Vincent Cerf, Chief Internet evangelist at Google and father of the Internet, sees computers becoming even more intelligent, with mobile phone ‘our companions rather than simply a device’ (Ericsson, 2013). Yet changes in the climate and unsustainable pollution in China does mean the world could follow the way of the Roman and Mayan civilisations, by simply collapsing. Technology will help, but leadership matters more and leadership at different levels. Technology may have been a catalyst that brought down the Soviet Union but, with political power more diffuse, politicians should perhaps be humble and open minded. The same could be said for business leaders, not to mention media pundits.

Futurologist, Anne Lise Kjaer, argues (EUROSME Conference, 2013) that because only one in five company or product brands are perceived to make any meaningful difference to peoples’ lives, institutions must begin to explore how to deliver ‘real’ value to communities. The Samso Energy Academy in Denmark demonstrates how decentralised collaboration, innovation and empowerment are key components of citizen participation. These are bonded by ‘authentic story-telling’. Sandra Macleod, CEO of Mindful Reputation, sums it up thus: ‘As risk becomes more complex, transparency more radical and reputation more dear with trust as the prize, through better alignment with stakeholder values and expectations, attention to authentic reputation creates very real value’ (2014). Whereas, in a rational context, Kjaer maintains, the key values are diversity and dialogue, in an emotional one, community and engagement values should be added. She talks about the era of ‘meaningful consumption’, promoting ‘radical openness’ as key to the digital reputation economy. She refers to her home country Denmark as having the lowest corruption in the world due to its transparent system of E-Government. There is a need for sharing, mobility and affinity, aided by ‘big data networks’. Social capital and shared values are the drivers of global economic clusters. In a hyper-connected society, social trends have the ability to reach further and move faster with grassroots concerns reaching a global audience. To create a ‘multi-dimensional’ future will require left-brain facts and analysis together with right-brain bigger picture, conceptual thinking, Kjaer asserts. The twentieth-century left-brain outlook driven by ego, power, status and wealth is obsolete and should be replaced by caring, community and the environment. Companies will win if they are able to manage the data deluge and complexity while also connecting with people for the purpose of inspiring and enriching their lives. The information revolution is replacing one kind of management (command and control) with another (self-organising networks), to create societal as well as economic value. This is now part of how business should be done.

It is no accident that Pope Francis in his first ‘Apostolic Exhortation’ wrote of the need for ‘an inclusive and compassionate church’ to offset the ‘globalisation of indifference’. Since then he has demonstrated this in various ways.

The End of History?

Thus, while we may not have reached ‘The End of History’ as Francis Fukuyama predicted in 1990, symbolised by the fall of the Berlin Wall, with many different shades of government and hues of capitalism being practised, the world has arguably reached a ‘critical juncture’. In summary, as a result of ‘ideas on the rise’ and ‘a bad mood rising’, the ever more sophisticated consumer/citizen determines the ‘licence to operate’. We live in a stakeholder-centric world!

The growth of more powerful stakeholders has hit business. Now a simple count of the global top 500 companies that did not exist ten years ago shows how relative newcomers are replacing them. In the second half of 2010, the midst of the economic recession, the top ten hedge funds (most unknown names) earned more than the worlds’ largest banks combined. The world’s largest steel company Arcelor-Mittal has ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication Dr Millicent Danker (1950–2013)

- Foreword

- PART I MEETING THE GLOBAL CHALLENGE: A COLLABORATIVE PARADIGM

- PART II REDEFINING THE PURPOSE OF BUSINESS

- PART III SHAPING STAKEHOLDER STRATEGIES

- PART IV LIFELONG LEARNING AND KNOWLEDGE SHARING

- The Past is Prologue

- Bibliography and Recommended Reading

- Index