- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

The enclosed garden, or hortus conclusus, is a place where architecture and landscape come together. It has a long and varied history, ranging from the early paradise garden and cloister, the botanic garden and giardini segreto, the kitchen garden and as a stage for social display. The enclosed garden has continued to develop into its many modern forms: the city retreat, the redemptive garden, the deconstructed building. As awareness of climate change becomes increasingly important, the enclosed garden, which can mediate so effectively between interior and exterior, provides opportunities for sustainable design and closer contact with the natural landscape. By its nature it is ambiguous. Is it an outdoor room, or captured landscape; is it architecture or garden?

Kate Baker discusses the continuing relevance of the typology of the enclosed garden to contemporary architects by exploring influential historical examples and the concepts they generate, alongside some of the best of contemporary designs – brought to life with vivid photography and detailed drawings – taken primarily from Britain, the Mediterranean, Japan and North and South America. She argues that understanding the potential of the enclosed garden requires us to think of it as both a design and an experience.

Captured Landscape provides a broad range of information and design possibilities for students of architectural and landscape design, practising architects, landscape designers and horticulturalists and will also appeal to a wider audience of all those who are interested in garden design.

This second edition of Captured Landscape is enriched with new case studies throughout the book. The scope has now been broadened to include an entirely new chapter concerning the urban condition, with detailed discussions on issues of ecology, sustainability, economy of means, well-being and the social pressures of contemporary city life.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1 Defining the territory

Discovery

Exploring the idea

Fisherman’s allotment in the Dunes with vegetable plots, with boundary clearly marked out. Wimmenummer Duinen Egmond aan Zee, North Holland.

Church and graveyard protected by wall in open countryside in Les Alpilles, France.

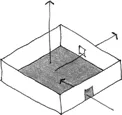

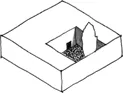

Limits to limited space.

Restricted views.

Room in a building.

Hidcote Manor, UK hedges act as walls to the Red Borders garden, and a retaining wall finishes off one of the sides, together with an architectural statement of two symmetrically placed pavilions. The orderly rows of severely-cut, pleached hornbeams complete the enclosure at a higher level, and provide us with a visual connection to the next ‘room’, and a restricted view of the land beyond it.

An enclosed garden in Cordoba is used for a business meeting when it is still shaded and pleasantly cool.

Characteristics and component parts

The whole question of the rela...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Defining the territory: the ambiguous nature of an enclosed garden

- 2 From patio to park: the enclosed garden as a generator of architectural and landscape design

- 3 Taming nature – and the way to Paradise

- 4 Ritual and emptiness – and the rigour of developing an idea

- 5 Sensory seclusion: the affective garden as a scene for living

- 6 Detachment: the separation of the garden from the building

- 7 Green city: the persistence of urban gardens

- Selected bibliography

- Illustration credits

- Index