eBook - ePub

Class Structure in Europe

New Findings from East-West Comparisons of Social Structure and Mobility

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Class Structure in Europe

New Findings from East-West Comparisons of Social Structure and Mobility

About this book

Is there a typical European class structure? Have power patterns left any imprint in the European societies of today? Has the experience of socialist revolution in Eastern Europe created a distinctive social-structural pattern in that part of the continent? These are only a few of the questions taken up by the contributors to this collection of case studies and comparative research.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Class Structure in Europe by Max Haller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Class and Social Structures in Europe and Beyond

Comparing Class Structures and Class Consciousness in Western Societies

DIETER HOLTMANN and HERMANN STRASSER

Between 1985 and 1987 we conducted a study on class structure and class consciousness in the Federal Republic of Germany, based on a representative sample of the West German labor force. It was funded by the German Science Foundation and carried out at the University of Duisburg. The study is part of a comparative project initiated by Erik Olin Wright (University of Wisconsin, Madison) in which a number of nationally funded research teams run essentially comparable surveys. Besides West Germany, the Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland), Great Britain, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have taken part. Surveys have also been started in Japan and in the first socialist country to be included, the USSR, but we cannot take these two cases into account because we have not yet obtained the data. Since the completion of the national study on West Germany (cf. Erbslöh et al. 1987, 1988), a new project under the direction of Dieter Holtmann has been funded by the German Science Foundation to analyze the similarities and differences of the German findings with respect to the countries mentioned above. It is in this context that we present our first results.

As point of reference we start with an analysis of the German class structure. Since, for the FRG, we found that Wright’s model II performs best in the statistical explanation of the variation in class consciousness, and a model of employment status performs best in the statistical explanation of the hierarchy of income, we elaborate these two models for the FRG and test the results against those for the United States and Sweden. As most of the discussions concerning the other countries in the comparative project are based on Wright’s model I, we base the rest of the analyses on that model. First, similarities and differences with the Scandinavian class distributions are discussed, along with gender contrasts. Then, following this comparison of the “welfare states,” we examine the class structure of Great Britain, as the prototype of a “liberal” political-economic regime, and try to determine where the FRG ranges with respect to this possible polarity. Next, we take a look beyond the European context and compare the class structure of the United States with the European configurations. Afterwards, we investigate in which way the concepts of semi-periphery, dominion capitalism, and the Americanization effect, which have been proposed for the cases of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, affect the European context. We then generate a typology of class structures on the basis of the distances of the class profiles. This typology demonstrates that the political-economic regimes are less important for structuring the class structures than one might previously have thought. Finally, we conclude by extending the discussion on “Europe in crisis” by formulating the main challenge to Europe as well as to the United States; for this challenge the hierarchy of “export efficiency” (Bornschier 1988) is of prime importance.

1. European configurations

1.1 Class structure and class consciousness in the FRG

The German project group has concentrated on the question of whether the class models selected satisfactorily define social locations that are homogeneous with respect to the following dimensions: the hierarchy of material locations (income turned out to be the best indicator) and class consciousness as an indication of future action of some probability (measured by a simple additive index of attitudes toward capital-versus-labor issues).1

Although the surveys of the comparative project are especially suited to test Wright’s models, we did not confine the analysis to those models but considered a series of class models for the FRG. According to our criteria, the German social statistics performed best with respect to the hierarchy of material location, and a modified version of Wright’s new model (Wright II) performed best with regard to the index of class consciousness. This is one of the reasons why we prefer Wright II over his older model (Wright I).

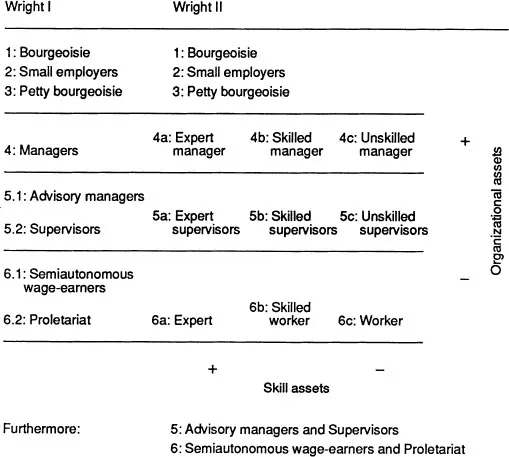

Since some of the national project teams have made comparisons on the basis of Wright I, we briefly summarize the rationale of both of Wright’s class models (cf. Table 1). Beyond the simple Marxian dichotomy of bourgeoisie and proletariat, Wright emphasized in his first model the “revolution of the managers.” He conceptualized the positions of managers as “contradictory class locations,” as they share common features with both main classes: they are employees, but decide and direct at the work place; the extent of this authority distinguishes top and advisory managers from supervisors. The petty bourgeoisie owns the means of production but is not an employer, while small employers range between bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie in that they–unlike the bourgeoisie–themselves work in office and factory. Finally, the semi-autonomous wage-earners do not decide and control at the work place, but have more or less autonomy in determining how to carry out work. Wright thought of this group as ranging between the proletariat and the petty bourgeoisie. However, as we expected, in the FRG this group is located between the proletariat and the different types of managers. We suppose that the same is true for the other countries. But this location is fairly heterogeneous, which is one reason why Wright used skill instead of autonomy in his new model.

Table 1

Wright’s Class Models

The major shift to the new model came about by integrating Roemer’s concept of asset exploitation (Roemer 1982), based on game theory, into Wright II. Besides the assets of the means of production, Wright considers organizational assets (as in Wright I) as well as skill assets (unlike in Wright I). Since there is no mechanism explicated by which, for instance, the skilled exploit the unskilled, we prefer to characterize Wright’s new model as one of resource inequality, and not of asset exploitation. This is also in line with Roemer’s (1986) most recent contribution, according to which a critical analysis of society should abandon the problematic concept of exploitation and concentrate on the inequality of assets.

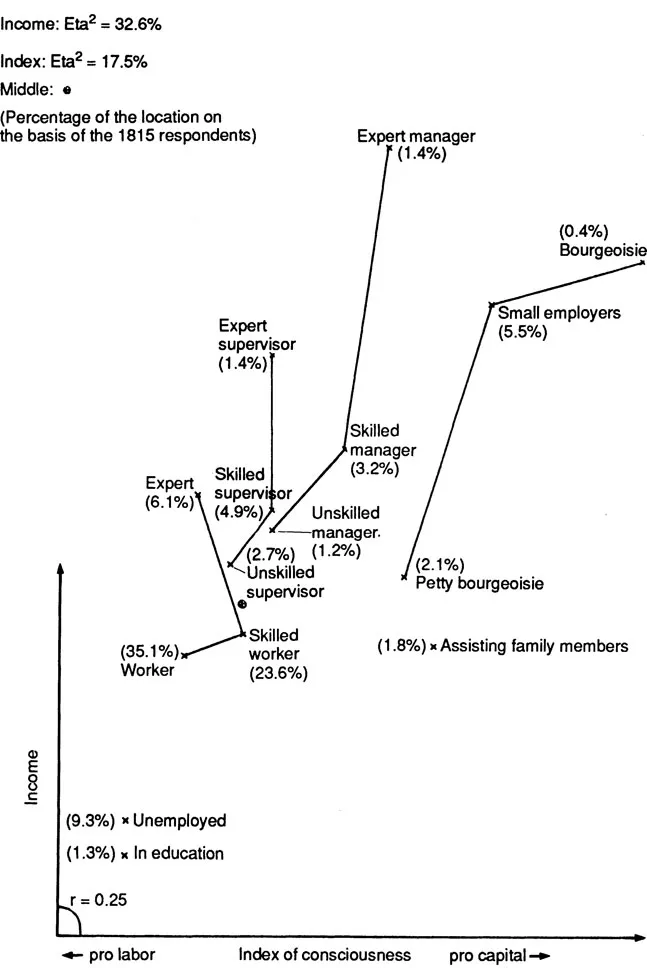

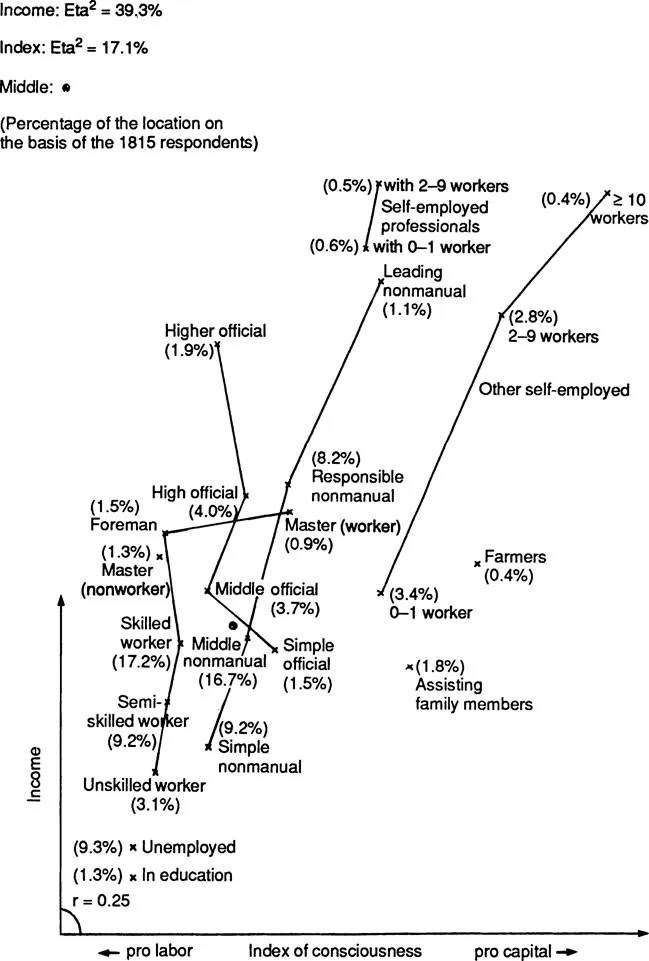

As a test of the different class models we used simple variance analyses of the criteria by the class models; and to evaluate propositions about orderings or about the configuration of a cross-tabulation in Wright II, we constructed a graphical frame of reference in which income is used as vertical axis and the index of consciousness as horizontal axis. Unlike factor analysis or multidimensional scaling, we chose as our two main criteria orthogonal axes of reference, even though they correlate slightly (r = 0.25).

In Figure 1 we examine whether Wright II sheds some light on the social structure of the FRG. Wright’s new model consists of a kind of cross-classification of management resources and skills, as far as employees are concerned. In our graph we should find the parallels of this cross-classification, if Wright’s model perfectly fits the German data. We think that the most interesting result on the basis of Wright II is the way in which it is not suited to the German data, the reason being that skill and consciousness are not related in a linear fashion, as we should expect according to Wright’s model. Instead, they are related in a curvilinear way. The unskilled workers show the most pronounced attitude “pro labor” (mean 5.63), the skilled the strongest attitude “pro capital” (mean 5.14), whereas the experts range approximately in the middle (mean 5.26). This phenomenon is stable for other definitions of skill and other indicators of consciousness. Figure 1 shows that this curvilinearity is essentially linked to the unskilled: there is an interaction according to which the curvilinearity shifts with increasing organizational assets in the direction of the linearity expected for all subgroups on the basis of Wright II. The skilled range ideologically more to the right than their income–compared to the other locations–should have us believe. As an explanation we suggest that there are still remarkable differences in consciousness between manual and nonmanual occupations, even if their material situation is similar.

These kinds of differentiation will be elaborated upon now by using a model based on the German social statistics (cf. Figure 2) which, at the moment, is probably best suited to picture the German social structure. Self-employed professionals and other self-employed have more income and range more to the “right” (that is, “pro capital”), the more workers they employ. The three locations of other self-employed nearly range on a linear trend. The self-employed professionals range more to the middle; this suggests that they are strongly influenced by their high educational level, indicating more liberal attitudes formed by their university experience. The farmers range farther to the right than they would be expected to on the basis of their income alone. The assisting family members of the self-employed receive lower incomes than the self-employed themselves (according to social statistics these family members are supposed to have no income, but most of them answer the question concerning income). Among the nonmanual workers in the FRG, the officials or civil servants are the most privileged with respect to social security (not always with regard to income). In the FRG the educational system allocates fairly rigidly the access to the occupational system; this holds especially for the civil service (cf. Müller 1986). Ideologically, the officials are located in the middle of the two extremes, even if they are high in rank and therefore also in income. This may be explained by the neutral position of the state and the civil service concerning capital versus labor issues, apart from the fact that a civil servant does not directly depend on a private capitalist. The other nonmanual workers show different attitudes: there is a nearly perfect linear trend according to which the nonmanual workers receive more income the higher their management position is, and are located more to the “right.” The manual workers range left of the middle and are fairly homogeneous, with the exception of the factory stewards or master workers, who, ideologically, range close to the employers. (The factory stewards who are nonworkers, as defined by the German social security system, are located close to the foremen.) Finally, the unemployed range closely below the unskilled workers; and still being an apprentice also seems to be a disadvantageous position in the German social structure.

Therefore, from the employment–status model, we would derive the hypothesis that the existence of a large civil service will likely diminish the polarity of capital versus labor, since civil servants are not directly dependent on private entrepreneurs and hence are more likely to be neutral in socio-political issues concerning capital and labor.

The curvilinearity of skill and consciousness that we have found for the FRG on the basis of Wright II will now be pursued in a preliminary test with nation as the context of analysis–a strategy strongly advocated by Melvin Kohn in his presidential address “Cross-National Research in Sociology” at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association in 1987. If we take the United States and Sweden as prototypes of a liberal state and a welfare state, then we have a hard test if the German phenomenon is of no particularity. If we take the results published by Wright (1985) on the basis of the two national surveys, the corresponding graphs show different configurations. There are nationally specific interactions of skill and consciousness. Of course, there is always the possibility that these data must be rearranged before a convincing configuration can be detected. This is why we are not yet reproducing all the figures, but are only giving a first hint which we hope is more robust than we assume to be the case for the preliminary configurations of the United States and Sweden: the German social structure resembles the Swedish one more closely; the differences in income are much larger in the United States than in the FRG or in Sweden. In particular, the top group of the self-employed receive very high incomes in the United States, whereas in the FRG and in Sweden the top executives are about on the same income level as the top of the self-employed. Ideologically, in the FRG and in Sweden the self-employed show a configuration which is separable from that of the employees, whereas in the United States the self-employed seem to be continuously growing out of the employees in a kind of continuum.

When we consider Wright II and the German social statistics together, we generate the following hypotheses: the larger civil services (as in the FRG and in Sweden) constitute the basis of ideologically neutral locations, as civil servants do not depend on private capitalists. The civil service offers a lot of careers for employed professionals with rewards resembling those at the top of the self-employed. Since the FRG and Sweden nevertheless turn out to have higher levels of class consciousness than the United States, other factors or social institutions must be accounted for. We assume that the tradition of the labor movement, especially the trade unions and labor parties, has paved the way for more class consciousness in the FRG and in Sweden. In the United States, on the other hand, the ideology that everyone is a potential private capitalist seems to have been more successful, possibly based on the numerous opportunities in a large country. Erikson and Goldthorpe (1985) recently did not find much empirical support for that explanation. Another factor is the cultural heterogeneity of the U.S. labor force, which impedes the development of class consciousness. Perhaps that is why in the United States we observe a greater spread in income and a lower class consciousness at the same time.

We next turn to several Scandinavian welfare states and to Great Britain to see if the FRG is more closely linked to one of these types of society or, perhaps, is located between them.

1.2 Scandinavian configurations

Some of the early surveys of the comparative project have been analyzed by the national project teams only on the basis of Wright I and the labor force with...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Editor’s Introduction

- Part I Class and Social Structures in Europe and Beyond

- Part II Educational Systems and Patterns of Mobility

- Part III Mobility Regimes in East Central Europe: Did Socialist Revolution Make a Difference?

- Index