![]()

Part I

Prehistory

Content

1 Introducing World Prehistory

![]()

Chapter 1

Introducing World Prehistory

An obelisk at the temple of the sun god Amun at Luxor, Egypt, 1838, by David Roberts.

(Niday Picture Library/Alamy)

Chapter Outline

“In the Beginning” …

Pseudoarchaeology

Prehistory, Archaeology, and World Prehistory

Major Developments in Human Prehistory

Cyclical and Linear Time

Written Records, Oral History, and Archaeology

Studying World Prehistory

Culture

Culture History, Time and Space, and the Myth of the Ethnographic Present

Cultural Process and Past Lifeways

The Mechanisms of Culture Change

Culture as Adaptation

Intangibles: Ideology and Interaction

Prologue

Egypt: the Valley of the Kings, November 1922. The two men paused in front of the doorway that bore the seals of the long-dead pharaoh. They had waited six long years, from 1917 to 1922, for this moment. Silently, Howard Carter pried a hole through the ancient plaster. Hot air rushed out of the small cavity and massaged his face. Carter shone a flashlight through the hole and peered into the tomb. Gold objects swam in front of his eyes, and he was struck dumb with amazement.

Lord Carnarvon moved impatiently behind him as Carter remained silent.

“Can you see anything?” he asked, hoarse with excitement.

“Yes, wonderful things,” whispered Carter as he stepped back from the doorway.

They soon broke down the door. In a daze of awe, Carter and Lord Carnarvon wandered through the antechamber of Tutankhamun’s tomb. They touched golden funerary beds, admired beautifully inlaid chests, and examined the pharaoh’s chariots stacked against the wall. Gold was everywhere—on wooden statues, inlaid on thrones and boxes, in jewelry, even on children’s stools. Soon Tutankhamun was known as the golden pharaoh and archaeology as the domain of buried treasure and royal sepulchers. Tutankhamun’s magnificent tomb is a symbol of the excitement and romance of archaeology.

Since time immemorial, humans have been intensely curious about their origins, about the mysterious and sometimes threatening world in which they exist. They know that earlier generations lived before them, that their children, their grandchildren, and their progeny in turn will, in due course, dwell on earth. But how did this world come about? Who created the familiar landscape of rivers, fields, mountains, plants, and animals? Who fashioned the oceans and seacoasts, deep lakes, and fast-flowing streams? Above all, how did the first men and women settle the land? Who created them—how did they come into being? Every society has creation stories to account for human origins. However, archaeology and biological anthropology have replaced legend with an intricate account of human evolution and cultural development that extends back to around 2.5 million years ago. This chapter describes how archaeologists study and interpret human prehistory.

“In the Beginning” …

We Westerners take the past for granted and accept human evolution as something that reaches back many millions of years. Science provides us with a long perspective on ancient times. Contrast our perspective with that of the Mataco Indians from South America, whose classic origin myth begins with cosmic fire. “After the Great Fire destroyed the world and before the little bird Icanchu flew away, he roamed the wasteland in search of First Place. The homeland lay beyond recognition, but Icanchu’s index finger, of its own accord, pointed to the spot. There he unearthed the charcoal stump that he pounded as his drum. Playing without stopping, he chanted with the dark drum’s sounds…. At dawn on the new Day, a green shoot sprang from the coal drum and soon flowered as Firstborn Tree…. From its branches bloomed the forms of life that flourished in the new World….” (Sullivan, 1988, p. 92) Like all such accounts, the tale begins with a primordium (the very beginning) in which a mythic being, in this case Icanchu, works to create the familiar animals, landscapes, and plants of the world, and then its human inhabitants. Icanchu, and his equivalents in a myriad of human cultures throughout the world, create order from primeval chaos, as God does in Genesis 1.

Myths, and the rituals and religious rites associated with them, function to create a context for the entire symbolic life of a human society, a symbolic life that is the very cornerstone of human existence. The first human beings establish the sacred order through which life endures from one generation to the next. This kind of history, based on legend and myth, is one of symbolic existence. Creation legends tell of unions between gods and monsters or of people emerging from holes in the earth after having climbed sacred trees that link the layers of the cosmos. They create indis-soluble symbolic bonds between humans and other kinds of life, such as plants, animals, and celestial beings.

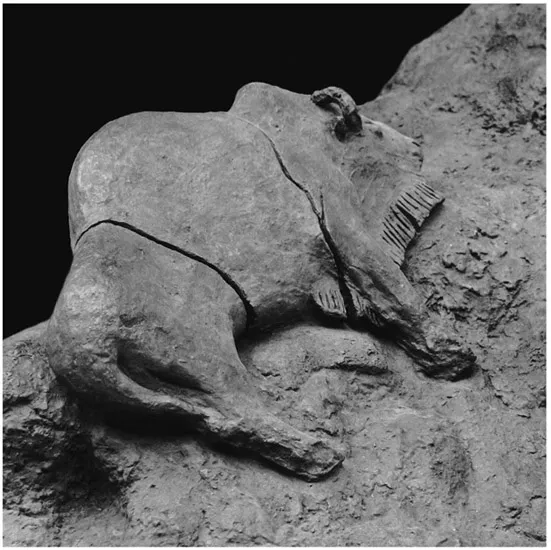

The vivid and ever-present symbolic world has influenced the course of human life ever since humans first acquired the power of creative thought and reasoning. The Cro-Magnons of late Ice Age Europe depicted mythical animals and the symbolism of their lives in cave paintings more than 30,000 years ago (see Chapter 4). They modeled clay bison in dark chambers deep beneath the earth (Figure 1.1). The sculptures seemed to flicker in the light of firebrands during powerful rituals that unfolded far from daylight. So compelling was the influence of the unknown powers of the cosmos and of the gods that inhabited it that the Maya and other Central American civilizations created entire ceremonial centers in the form of symbolic landscapes to commemorate their mythic universe (see Chapters 12 and 13).

Today, Western science has chronicled an extremely lengthy and unfolding prehistory. This story is based on scientific research, something quite different from the creation legends that people use to define their complex relationships with the natural and spiritual worlds. These legends are deeply felt, important sources of cultural identity. They foster a quite different relationship with the past than that engendered by archaeology, which seeks to understand our common biological and cultural roots and the great diversity of humanity.

Figure 1.1 Late Ice Age masterpieces: two clay bison from Le Tuc D’Audoubert, France.

(World History Archive/Alamy)

Pseudoarchaeology

Golden pharaohs, lost civilizations, buried treasure—archaeology seems like a romantic world of high adventure and exciting discovery. A century ago, archaeology was indeed a matter of exotic travel to remote places. It was still possible to find a hitherto unknown civilization with a few weeks of digging. Today, archaeology is a highly scientific discipline, concerned more with minute details of ancient life than with spectacular discoveries. But an aura of unsolved mysteries and heroic figures still surrounds the subject in many peoples’ eyes—to the point of obsession.

The mysteries of the past attract many people, especially those with a taste for adventure, escapism, and science fiction. These people create elaborate adventure stories about the past—almost invariably epic journeys or voyages based on illusory data. For example, British journalist Graham Hancock has claimed that a great civilization flourished under Antarctic ice 12,000 years ago. (Of course, its magnificent cities are buried under deep ice sheets, so we cannot excavate them!) Colonists spread to all parts of the world from their Antarctic home, occupying such well-known sites as Tiwanaku in the Bolivian highlands and building the Sphinx by the banks of the Nile. Hancock weaves an ingenious story by piecing together all manner of controversial geological observations and isolated archaeological finds. He waves aside the obvious archaeologist’s reaction, which asks where traces of these ancient colonies and civilizations can be found in Egypt and other places. Hancock fervently believes in his far-fetched theory, and being a good popular writer, he has managed to piece together a best-selling book that reads like a “whodunit” written by an amateur sleuth.

Flamboyant pseudoarchaeology of the type Hancock espouses will always appeal to people who are impatient with the deliberate pace of science and to those who believe in faint possibilities. It is as if a scientist tried to reconstruct the contents of an American house using artifacts found in Denmark, New Zealand, South Africa, Spain, and Tahiti.

Nonscientific nonsense like this comes in many forms. There are those who believe that the lost continent of Atlantis once lay under the waters of the Bahamas and that Atlanteans fled their sunken homeland and settled the Americas thousands of years ago. Others fantasize about fleets of ancient Egyptian boats or Roman galleys that crossed the Atlantic long before Columbus. All these bizarre manifestations of archaeology have one thing in common: they are overly simple, convenient explanations of complex events in the past, based on such archaeological data as their author cares to use.

These kinds of pseudoarchaeology belong to the realms of religious faith and science fiction. The real science of the past is based on rigorous procedures and meticulous data collection, its theorizing founded on constantly modified hypotheses tested against information collected in the field and laboratory—in short, archaeological, biological, and other evidence.

Prehistory, Archaeology, and World Prehistory

Human beings are among the only animals that have a skeleton adapted for standing and walking upright, which leaves our hands free for purposes other than moving around. A powerful brain capable of abstract thought controls these physical traits. The same brain allows us to communicate symbolically and orally through language and to develop highly diverse cultures—learned ways of behaving and adapting to our natural environments. The special features that make us human have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years.

The scientific study of the past is a search for answers to fundamental questions about human origins. How long ago did humans appear? When and how did they evolve? How can we account for the remarkable biological and cultural diversity of humankind? How did early humans settle the world and develop so many different societies at such different levels of complexity? Why did some societies cultivate the soil and herd cattle while others remained hunters and gatherers? Why did some peoples (for example, the San foragers of southern Africa or the Shoshone of the Great Basin in North America) live in small family bands, while the ancient Egyptians and the Aztecs of Mexico built highly elaborate civilizations (Figure 1.2)? When did more complex human societies evolve and why? The answers to these questions are the concern of scientists studying world prehistory.