![]()

Part I

Understanding the Roots of Aggression and Violence in Humans

![]()

1

An Integrative Theoretical Understanding of Aggression

In this chapter I lay out the most important key principles for understanding the occurrence of aggressive behavior. These are principles that have emerged out of many decades of research on aggression but also draw on key findings from social, cognitive, and developmental psychology. Aggressive behavior is a social behavior, is influenced by peoples’ cognitive processing, and changes over the developmental life course.

In the context of this chapter, aggressive behavior is any behavior intended to injure or irritate another person (Berkowitz, 1974, 1993; Eron et al., 1972). Psychologists have usually distinguished between the kind of aggressive behavior that is directed at the goal of obtaining a tangible reward for the aggressor (instrumental or proactive aggression) and the kind of aggressive behavior that is simply intended to hurt someone else (at different times denoted hostile, angry, emotional, or reactive aggression) (Berkowitz, 1993; Dodge & Coie, 1987, Feshbach, 1964). Nevertheless, an examination of the underlying cognitive processes involved (e.g., Dodge & Coie, 1987) has led to a realization that many of the same mechanisms are involved in both types of aggression (Bushman & Anderson, 2001); so many of the principles I describe in this chapter apply to both types. Finally, violent behavior is defined simply as an extreme form of aggressive behavior in which the target of the behavior is actually physically harmed, e.g., hit, punched, choked, beaten, bludgeoned, stabbed, shot.

Four Important Principles about the Occurrence of Aggressive Behavior

First, aggressive behavior, like other social behaviors, is always the product of personal predispositions and precipitating situational determinants. Personal predispositions are influenced over time by a variety of biological and environmental influences that lead to the development of characteristic emotional reactions, cognitions, and cognitive processing. Consequently, some people grow up to be more predisposed to behave more aggressively in almost any situation. Situational determinants then prime the cognitions and emotional reactions linked to the situation in associative memory (Bargh & Pietromonaco, 1982; Fiske & Taylor, 1984). Extreme situations can instigate almost anyone to behave aggressively.

Second, habitual aggressive behavior usually emerges early in life, and early aggressive behavior is very predictive of later aggressive behavior and even of aggressive behavior of offspring (Farrington, 1985; Huesmann et al., 1984; Olweus, 1979). Process models for aggressive behavior explain this continuity over time and across generations by the development of cognitive and emotional predispositions to aggression that last over time.

Third, predispositions to severe aggression are most often a product of multiple interacting social and biological factors (Huesmann, 1997), including genetic predispositions (Cloninger & Gottesman, 1987; Mednick et al., 1984), environment/ genetic interactions (Caspi et al., 2002; Lagerspetz & Lagerspetz, 1971), central nervous system (CNS) trauma and neurophysiological abnormalities (Moyer, 1976), early temperament or attention difficulties (Kagan, 1988), arousal levels (Raine et al., 1990), hormonal levels (Olweus et al., 1988), family violence (Widom, 1989), cultural perspectives (Staub, 1996), poor parenting (Patterson, 1995), inappropriate punishment (Eron et al., 1971), environmental poverty and stress (Guerra et al., 1995), peer-group identification (Patterson et al., 1991), and other factors. No one causal factor by itself explains more than a small portion of individual differences in aggressiveness.

Fourth, early learning plays a key role in the development of a predisposition to habitually behave in an aggressive or nonaggressive manner. Most children need to be socialized out of the aggressive inclinations stimulated by the normal or abnormal personal factors mentioned above and taught self-control. Some children are never socialized out of aggression, and some children are socialized into more frequent and serious aggression. From a social cognitive perspective, the variety of predisposing factors discussed above may make the emergence of certain specific cognitive routines, scripts, and schemas more likely, but these cognitions are likely to be unlearned or more firmly learned through interactions of the child with the environment. Aggression is most likely to develop in children who grow up in environments that reinforce aggression, provide aggressive models, frustrate and victimize them, and teach them that aggression is acceptable.

Social Information Processing

In the past few decades it has become clear that to understand how, why, and when human aggressive and violent behavior occurs one has to understand how humans process social information in their brains. Building on the earlier theoretical formulations of Berkowitz (1974), Bandura (1973), and Eron (Eron et al., 1971), aggression researchers have established a number of principles of social information processing that explain much better than ever before both the processes by which predispositions to aggression are formed within a person, and the processes by which situations interact with these predispositions to instigate the individual to behave aggressively (e.g., Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dewall et al., 2011; Dodge, 1986; Huesmann, 1988, 1998; Huesmann & Kirwil, 2007).

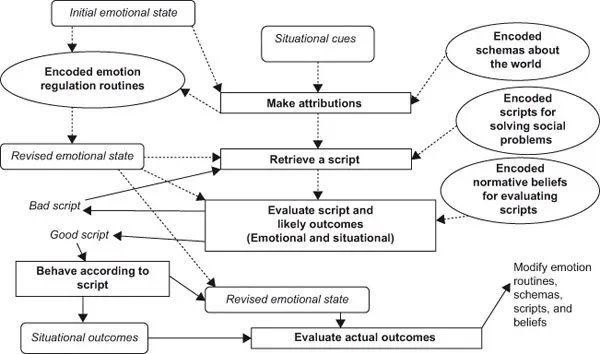

The principles are best understood by viewing social interactions as a series of social problem-solving situations. The individual in any social situation has to decide how to behave—that is, how to solve the social problem. What has been discovered is that individuals—whether children or adults—go about this social problem solving rather systematically, even though they may be unaware of the information processing that they are doing. The process begins with evaluation of the social situation and ends with the decision to behave in a certain way, followed by a post hoc self-evaluation of the consequences of behaving that way. These processes may be automatic and out of awareness or they may be consciously controlled (Bargh & Pietromonaco, 1982; Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977; Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977). The sequence of processes based on the work of Anderson and Bushman (2002), Dodge (1980), and Huesmann (1988, 1998) is diagrammed in Figure 1.1.

These processes operate in human memory, which we now know can best be represented as a complex associative network of nodes representing cognitive concepts and emotions. There are many associative links between the nodes—some built in from birth and some established through learning experiences. Some links are stronger than others. When a node is activated by an external stimulus, activation “spreads out” from that node to linked nodes in proportion to how strong the links are. The activation of a node or a network of nodes at a particular time is determined by how many links to it have been activated, as well as the strength of the links. “Meaning” is only given to a node by its associations with other nodes. When the total activation of a node or set of nodes becomes above a certain “threshold,” the “meaning” of the node is “experienced.” Activation is cumulative, and when a node’s activation level is increased but is still below threshold for “experiencing it,” we say it has been “primed.” Three particularly important knowledge structures relevant to social information processing are stored within a person’s associative memory: 1) their schemas about the world and other people used to evaluate social situations, 2) their repertoire of social “scripts” that guide behavior, and 3) their self-schemas, including their normative beliefs about what are appropriate behaviors for them. A social script (Abelson, 1981) is a program of behaviors and expected responses by the environment designed to solve a social problem. The fourth important knowledge structure relevant to social information processing is the set of emotion regulation routines a person has encoded in memory.

Figure 1.1 Information processing steps for social problem solving.

We now know that there are four loci in the social problem-solving process at which individual differences in emotion regulation, schemas, scripts, and beliefs interact with situational variations to influence social information processing and thus social behavior including aggression: 1) the evaluation of the situation, 2) the retrieval of potential scripts for behavior, 3) the filtering of such scripts through the lens of effectiveness and appropriateness, and 4) the interpretation of the outcome of the behavior.

Evaluation of the Situation

To begin with, the objective situation primes cognitive structures in the brain and emotional reactions. However, which environmental cues are given most attention and how they are interpreted may vary from person to person and may depend on a person’s neurophysiological predispositions, current mood state, and previous learning history. Negative affect (e.g., a bad mood) primes the interpretation of environmental events to be more negative. Very aversive situations and frustration will produce negative affect in almost everyone, but the intensity of the affect depends on the interpretation given to the situation. Environmental stimuli may directly trigger conditioned or unconditioned emotional reactions and may cue the retrieval from memory of cognitions that define the current emotional state. For example, the “sight of an enemy” or the “smell of a battlefield” may provoke both instantaneous physiological arousal and the recall of thoughts about the “enemy” that give meaning to the aroused state as anger. That emotional state may influence both what cues the person attends to and how those cues are evaluated. A highly aroused, angry person may focus on just a few highly salient cues and ignore others that convey equally important information about the social situation. Then the angry person’s evaluation of these cues may be biased toward perceiving hostility when none is present. A person who finds hostile cues the most salient or who interprets ambiguous cues as hostile is said to have a “hostile attributional bias,” and will be more likely to experience anger and activate schemas and scripts related to aggression.

Individuals who have greater characteristic tendencies to attribute hostility to even the benign actions of others tend to be more aggressive (Dodge, 1980). In fact, people who have such a “hostile attributional bias” are at high risk to be violent (Dodge et al., 1990). Furthermore, it is now known that this is a cross-cultural phenomenon. A higher tendency to make attributions of hostility about the benign actions of others is predictive of higher levels of aggression for individuals in many different societies (Dodge et al., 2015). More generally, attributions that a “bad” situation (a frustrating event or a failure to obtain an expected goal) is due to external causes, controllable by others, and due to unfair actions of others is a strong instigator to aggression for most people (Berkowitz, 1993). These attributions increase the likelihood of making a hostile attribution about the intentions of others and increase the priming of aggressive cognitions.

Retrieval of Potential Scripts for Behavior

After evaluating a social problem-solving situation, individuals then retrieve “scripts” that are associated in their memory with their evaluation of the situation. We know that more aggressive individuals have encoded in memory a more extensive, well-connected network of social scripts emphasizing aggressive problem solving. Therefore, such a script is more likely to be retrieved during any search. However, the likelihood of a particular script being retrieved is affected by one’s interpretation of the social cues and attributions about the situation as well as one’s mood state and arousal. If any of these prime the script, because they have been associated with the script in the past, the script is more likely to be retrieved. For example, bad moods, even in the absence of supporting cues, will make the retrieval of scripts previously associated with bad moods more likely. This leads to the principle: “When we feel bad, we act bad!” (Berkowitz, 1993). Similarly, the presence of a weapon, even in the absence of anger, will make the retrieval of scripts associated with weapons more likely (Berkowitz & LePage, 1967; Carlson et al., 1990), and the perception that another person has hostile intentions will activate scripts related to hostility. Finally, we know that angry, aroused people are less likely to engage in broad, time-consuming searches for a social script to follow and are more likely to focus on the first simple scripts that occur to them. Unfortunately, the first scripts that occur to them are likely to emphasize aggressive, retaliatory actions.

Filtering out Inappropriate Scripts

Before acting out a social script to try to solve a social problem, individuals have been shown to evaluate the script in light of internalized activated schemas and normative beliefs to determine if the suggested behaviors are socially appropriate and likely to achieve the desired goal. Normative beliefs are beliefs about what is “OK” or appropriate to do in a social situation (Guerra et al., 1994). Different people often evaluate the same script quite differently. Habitually aggressive people are known to hold normative beliefs condoning more aggression, and thus aggressive scripts are more likely to pass the filtering process for them than they are for habitually nonaggressive people. For example, if a man suddenly discovers that his wife has been unfaithful, he may experience rage, which primes the immediate retrieval of a script for physical retribution. However, whether or not the man executes that script will depend on his normative beliefs about the appropriateness of “hitting a female.” Even within the same person, different normative beliefs may be activated in different situations and different mood states. The person who has just been to church may have activated quite different normative beliefs than the person who has just watched a fight in a hockey game on TV.

Although evaluation of the script on the basis of one’s normative beliefs is probably the most important filtering process, two other evaluations also appear to play a role. Scripts include predictions about likely outcomes of behaviors, but people differ in their capacities to predict outcomes (e.g., positive or negative) accurately, and people discount future outcomes over current outcomes to different extents. More aggressive individuals tend to focus more on positive parts of the immediate outcome of using an aggressive script (e.g., an immediate tangible gain) and discount more future negative consequences or future positive outcomes of not behaving aggressively (i.e., they are less able to delay gratification).

This whole process of evaluating scripts against normative beliefs and desired goals and then deciding to follow or not follow a script is the essence of what most of us would call “self-control.” An individual who has a high ability to reject scripts that will not achieve desired goals or that violate the individual’s normative beliefs is an individual whom we say has high “self-control.”

Interpreting the Outcome of Using the Script, and Modifying Cognitions and Mood

The fourth locus for individual differences in this model is a person’s interpretation of society’s responses to his or her behaviors and how that interpretation affects the person’s schemas and mood. With some interpretations of society’s responses, one ...