eBook - ePub

The City Symphony Phenomenon

Cinema, Art, and Urban Modernity Between the Wars

- 342 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The City Symphony Phenomenon

Cinema, Art, and Urban Modernity Between the Wars

About this book

The 1920s and 1930s saw the rise of the city symphony, an experimental film form that presented the city as protagonist instead of mere decor. Combining experimental, documentary, and narrative practices, these films were marked by a high level of abstraction reminiscent of high-modernist experiments in painting and photography. Moreover, interwar city symphonies presented a highly fragmented, oftentimes kaleidoscopic sense of modern life, and they organized their urban-industrial images through rhythmic and associative montage that evoke musical structures. In this comprehensive volume, contributors consider the full 80 film corpus, from Manhatta and Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt to lesser-known cinematic explorations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The City Symphony Phenomenon by Steven Jacobs, Eva Hielscher, Anthony Kinik, Steven Jacobs,Eva Hielscher,Anthony Kinik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

part one

introduction

the city symphony phenomenon

1920–40

basic characteristics

The 1920s and 1930s saw the rise and development of dozens of films that were labeled city films, city poems, or, more commonly, city symphonies. Well-known examples include Manhatta (Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler, 1921), Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, Walter Ruttmann, 1927), Chelovek s kinoapparatom (Man with a Movie Camera, Dziga Vertov, 1929), Regen (Rain, Joris Ivens and Mannus Franken, 1929), and À propos de Nice (On the Topic of Nice, Jean Vigo, 1930). These films helped to invent the avant-garde nonfiction film by handling documentary footage of the modern city in ways that could be abstract, poetic, metaphorical, and rhythmic. Instead of serving as a mere backdrop for a story, the city, here, is the protagonist of the film—it is its primary focus, its impetus, the very material of which the film is fashioned. In addition, the city symphony recognizes the city as an emblem of modernity (perhaps the ultimate emblem of modernity), and its modernist form represents an attempt on the part of the filmmakers to use the rapidly expanding language of cinema to capture what László Moholy-Nagy once called “the dynamic of the metropolis.”1 The vast majority of these films are notable for their oftentimes imaginative, even daring, use of editing, and this cycle as a whole made a major contribution to the discourse of montage aesthetics that was such a crucial aspect of the interwar period, deeply affecting the realms of film, the visual arts, literature, theater, and so on. As the moniker “city symphony” suggests, these films were often edited in such a way as to suggest a musical structure. Shots were treated like musical notes, sequences were organized as if they were chords or melodies, scenes were built up into movements or acts, and issues of rhythm, tempo, and polyphony figured prominently. But in all cases, the substance of these works was the city itself—or, rather, its cinematic representation—and the effect that was achieved was more poetic than expository in contrast to earlier scenics or travelogues that focused on touring urban landscapes. At the same time, most of these films combined their experimental nonfiction form with some basic elements of narrative. They eschewed the lives of individuals, focusing instead on the larger patterns that make up the urban fabric, but they frequently made use of a temporal structure to keep things from becoming overly abstract. Thus, we have films that focus on mornings and nights in the big city, alongside more typical dawn-till-dusk, dawn-till-late night, and dawn-till-dawn configurations, but virtually all of these films insist that they be understood as one- day-in-the-life of the city (or, in rare examples, cities) in question, regardless of how many weeks or months it might have taken to shoot them in the first place.

Throughout the 1920s, the characteristic elements of the city symphony were established and codified, to the extent that its unusual perspectives, skewed angles, rapid and rhythmic montage, special effects, and iconography became a kind of cinematic shorthand for modern metropolitan life, one that would appear in quite a number of fictional feature films in the 1930s and beyond. Among other features, the city symphonies focused on the spaces of the contemporary city and the inhabitants who populated them, creating the sense of a cross-section of the locations, activities, and social groupings that constitute modernity, and they tended to give the impression that these images represented “life as it is,” or “life caught unawares,” as in Vertov’s famous turn of phrase.2 Many of these city symphonies were key contributions to the emergence of the documentary film in the 1920s and 1930s, however they avoid “pure” or “absolute” nonfiction form, and instead combine narrative elements with an emphatically experimental form. In fact, they frequently feature the use of abstraction and defamiliarization techniques reminiscent of contemporaneous experiments in avant-garde painting and photography, and the highly fragmented, oftentimes kaleidoscopic sense of modern life that they present is organized through rhythmic and associative montage in such a way as to evoke musical structures.

rise, development, and proliferation

The earliest examples of what can be called city symphony date from the early 1920s, when two key works were released. The first of these was Sheeler and Strand’s Manhatta, a ten-minute decisively modernist celebration of New York, which was conceived in 1919, shot in 1920, and received its theatrical premiere in 1921.3 The second was László Moholy-Nagy’s scenario A nagyváros dinamikája (Dynamic of the Metropolis, 1921–1922), a “Sketch of a Manuscript for a Film” whose urban-industrial iconography and attention to the “optical arrangement of tempo” would help codify the European city symphony in the years to come.4 First published in Hungarian in 1924, the screenplay was translated into German and combined with photographs and a modernist design in Moholy-Nagy’s 1925 Bauhaus book Malerei Photographie Film. Another important mid-1920s contribution to the phenomenon was Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures (Nothing but Time, 1926), a film that is actually primarily a work of fictional narrative, but one that makes great use of its urban locations and attempts to show one day in the life of Paris’s down and out districts over the course of 45 minutes. Interestingly, in spite of its obvious fictional trappings, Rien que les heures was released at a time when filmmakers, scholars, and theorists were conceptualizing the documentary film for the first time, and, for some reason, the film was seen as one by many, and it has been connected to the city symphony phenomenon ever since. According to John Grierson, in Cavalcanti’s film, “Paris was cross- sectioned in its contrasts—ugliness and beauty, wealth and poverty, hopes and fears. For the first time the word ‘symphony’ was used, rather than story.”5 Of course, Cavalcanti would go on to become one of the leading figures of the British documentary movement of the 1930s, which may help to explain why colleagues of his, like Grierson and Paul Rotha, were so eager to position Rien que les heures as a documentary. In any case, one of the ironies of the time was that at roughly the same time that Cavalcanti was producing and releasing his film, Robert Flaherty, the father of the modern documentary film, made Twenty-four Dollar Island (1927), but somehow this film tended to get overlooked by the same scholars.

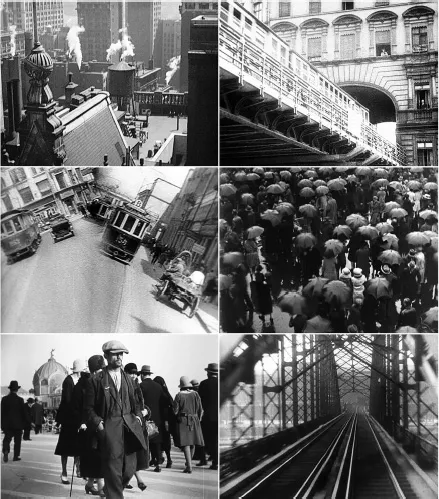

Figure I.1 Manhatta (Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand, 1921); Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt (Walter Ruttmann, 1927); Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929); Regen (Joris Ivens and Mannus Franken, 1929); À propos de Nice (Jean Vigo, 1930); and Jeux des reflets et de la vitesse (Henri Chomette, 1925)

However, if these early texts were progenitors, it was Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin which fully established the genre, touched off the phenomenon, and whose subtitle, Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt, provided this movement with its nickname. And it was Berlin more than another film that first demonstrated how the everyday life of the city could be transformed into a modernist work of art. Berlin also caused a sensation. The cycle that it touched off reached its apex almost immediately, and 1929 saw the release of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Moholy-Nagy’s Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen (Vieux Port) (Impressions of the Old Harbor of Marseille), Ivens and Franken’s Regen, Lucie Derain’s Harmonies de Paris (Harmonies of Paris), Corrado D’Errico’s Stramilano, Henri Storck’s Images d’Ostende (Images of Ostend), and Robert Florey’s Skyscraper Symphony, among others. By the late 1920s and early 1930s, the city symphony form had attracted the interest of a large number filmmakers whose names would become prominent in the history of cinema: Marcel Carné, Manoel de Oliveira, Alexandr Hackenschmied (a.k.a. Alexander Hammid), Lewis Jacobs, Boris Kaufman, Mikhail Kaufman, Georges Lacombe, Jay Leyda, Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Herman Weinberg, and so on, in addition to the aforementioned Strand, Sheeler, Moholy-Nagy, Cavalcanti, Flaherty, Ruttmann, Vertov, Ivens, Florey, and Vigo. By the late 1930s, this group would also include such luminaries as Rudy Burckhardt, Ralph Steiner, and Willard Van Dyke. In addition to the cinematic explorations of Berlin, Moscow, Paris, and New York—the cities that inspired the most famous of these films—filmmakers also turned their “kino-eyes” on Nice, Marseille, Lourdes, Düsseldorf, Milan, Ostend, Porto, Prague, Rotterdam, Montreal, São Paulo, Liverpool, and many other places. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, many city symphonies were made and probably even more were planned but never realized. Alfred Hitchcock, for instance, flirted with the idea of making an experimental “film symphony” entitled London or Life of a City in collaboration with Walter Mycroft: “The story of a big city from dawn to the following dawn. I wanted to do it in terms of what lies behind the face of a city—what makes it thick—in other words, backstage of a city.”6

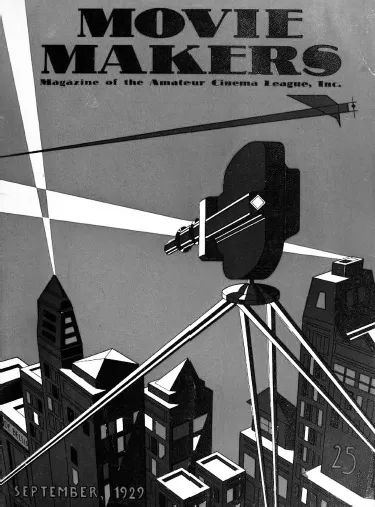

In the early 1930s, the city symphony cycle continued to expand and it simultaneously also became increasingly professionalized and commercialized as several municipal authorities commissioned films in the style of Ruttmann’s Berlin. Ruttmann’s own film can be understood on some level as a commissioned work, as it was produced as part of a quota program (”Kontingentfilm”) for Fox Europe. Other works, such as De Stad die nooit rust (The City that Never Rests, Andor von Barsy and Friedrich von Maydell, 1928), A Day in Liverpool (Anson Dyer, 1929), Praha v záři světel (Prague by Night, Svatopluk Innemann, 1928), Fukkõ Teito Shinfoni (Symphony of the Rebuilding of the Imperial Metropolis, anonymous, 1929), or Ruttmann’s Kleiner Film einer großen Stadt … der Stadt Düsseldorf am Rhein (Small Film for a Big City: The City of Düsseldorf on the Rhine, 1935), Stuttgart: die Großstadt zwischen Wald und Reben—die Stadt des Auslanddeutschtums (Stuttgart, the Big City Between Forest and Vines—The City of Germans Abroad, 1935), and Weltstrasse See, Welthafen Hamburg (The Ocean as World Route, Hamburg as World Port, 1938) were made for or in cooperation with commissioning agencies or municipalities and were not infrequently used for city promotional purposes or even propaganda. In other cases, such as Bonney Powell’s Manhattan Medley (1931), produced by Fox Movietone, or Gordon Sparling’s Rhapsody in Two Languages (1934), which deals with Montreal and was produced by the Canadian outfit Associated Screen News, we can see clear examples of the further commercialization of the city symphony film. However, the vast majority of city symphonies were independent productions or personal projects by artists, although some of these artists, like Vigo and Florey, were professionals working in the film business who made city symphonies as personal project on the side. In the September 1929 issue of Movie Makers, Marguerite Tazelaar captured this personal/professional split in a profile of Florey. Tazelaar writes that Florey, while working for big film studios, “spends his spare moments shooting experimental pictures with his small movie camera in the by-ways and highways of New York, Los Angeles, or where-ever he happens to be.” Inspired by Florey’s Skyscraper Symphony, Tazelaar concludes that “the city” is the perfect topic for amateur filmmakers interested in an “experimental approach.”7 This interest in avant-garde representations of the city was widespread in amateur film circles in the late 1920s and early 1930s, as for example Leslie P. Thatcher’s prize-winning city symphony Another Day (1934), Friedrich Kuplent’s Prater (1929), Lynn Riggs and James Hughes’s A Day in Santa Fe (1931), or Liu Na’ou’s Chi sheyingji de nanren (The Man Who Has a Camera, 1933) demonstrate. Harry Potamkin in his discussion of the “montage films” by Cavalcanti, Ruttmann, and Vertov, urged amateurs to film and critique everyday aspects of American life or people outside the private confines of the home.8 As Patricia Zimmermann noted, “It is significant that Potamkin cited examples of films about public places; these examples attacked the amateur movie magazine emphasis on private life and personal travel.”9

Figure I.2 Cover Illustration, Movie Makers (September 1929)

Many leading film critics and theorists of the period were inspired to write about these films, expressing intrigue, fascination, and, in some cases, consternation in response to this body of work. When he described the impact of Ruttmann’s Berlin, Grierson wrote,

No film has been more influential, more imitated. Symphonies of cities have been sprouting ever since, each with its crescendo of dawn and coming-awake and workers’ processions, its morning traffic and machinery, its lunchtime contrasts of rich and poor, its afternoon lull, its evening denouement in sky-sign and night club. The model makes for good, if highly formulaic, movies.10

Acknowledging the currency of “the symphonic form” or “symphony form” with aspiring filmmakers i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- contents

- illustrations

- preface

- acknowledgments

- part one

- part two

- part three

- about the contributors and editors

- about the american film institute

- index