- 98 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pottery and the Archaeologist

About this book

Collection of research papers concerning ceramic and ceramic analysis for archaeologists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pottery and the Archaeologist by Martin Millett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

POTTERY DISTRIBUTIONS: SERVICE AND TRIBAL AREAS

In order to provide a general framework for this essay, the idea of the ‘random spatial economy’ needs to be introduced. This is a general approach used by, for example, human geographers (Curry, 1964; 1967) and architects (Hillier et al., 1976), which attempts to provide a useful and productive working definition of pattern. The basis of the approach is that aggregate human behaviour can sometimes be compared with a random (stochastic) process. Such a comparison is only possible when there are many small or equal forces controlling and influencing the behaviour. When a few marked constraints are imposed, on the other hand, a clear patterning is produced in the behaviour and in the end-results of the behaviour. Thus, pattern is related, according to this theory, to non-randomness and the imposition of constraints.

In general, the stronger and fewer the constraints in operation, the more patterned is the end result (such as a settlement pattern or artifact distribution) of the process, and the more information can be gained about the behaviour from examination of the end result. With this view of things, the ‘randomness hypothesis’ can be used as a base against which to identify and measure the presence and play of constraints.

This general framework will be used in what follows in that the types of constraints which can cause patterning in pottery distributions will be considered. In moving from general to more specific constraints, the geographer’s and then the social anthropologist’s models will be examined.

The constraints which cause the more obvious patterning in most pottery distributions are necessarily trivial. In the first place, the friction effect of distance (people tend to travel more short than long distances) means that most pottery distributions will exhibit fall-offs in frequency away from the pottery source. If a random walk procedure is used as the underlying model of dispersal of pots from a source, then the first general constraint which needs to be introduced is some limit to distances moved in exchange transactions.

However, the friction effect of distance varies according to the nature of the pottery. In general, finer, more valuable wares might be expected to be traded over wider areas than coarse heavy wares. Such factors cause general changes in the nature of the fall-off frequency curves as has been shown by geographers (Morrill and Pitts, 1967; Taylor, 1971) and in archaeology (Hodder, 1974b) with the results further discussed by Renfrew (1977). Of course, this is only a general model and it is the cases which do not ‘fit’ which are often of greater interest. Thus, the very widespread distribution of coarse, heavy, Roman amphorae (Peacock, 1971) would be noted as an anomaly in terms of the predictions of the model even if it was not known that they were traded more for their contents than for the vessels themselves.

Another type of constraint which, as geographers (e.g. Carrothers, 1956) have frequently noted, plays a part in determining market patterns is that consumers and traders are attracted to larger centres from greater distances than they are to smaller centres. Unfortunately, a number of archaeologists (e.g. Sidrys, 1977) have recently overstressed the consequences of this situation. It has been noted that sites with higher frequencies or densities of a product which derives from a known source are often larger. The deduction is then made that these larger centres acted as service or redistributive centres for the surrounding areas. In fact, markedly larger quantities of material from a known source would be expected at larger sites even if they did not act as service centres. This is because, being larger and more complex, they may attract greater interaction from, and more intense trade with, the source. Such a situation is modelled by the gravity model (Carrothers, 1956) which states that the amount of interaction between centres i and j is directly related to their size, and inversely related to their distance apart. The model describes a complex relationship between size, distance and interaction, and it is not possible to assume that a greater frequency of pottery from a source per head of population in larger sites implies some special function or hierarchical position for these sites (Renfrew, 1977: 85). The relative frequency of the pottery in larger and smaller sites may tell us about the relative attractiveness of the centres and the appropriate parameters for the gravity model., It does not, by itself, tell us anything about the functioning of the centres.

The relative amount or density of pottery from a known source cannot be used to identify whether Roman walled towns, for example, were being used as redistributive centres. It is difficult to see how the existence of service centres and areas can be demonstrated without more detailed analysis of, for example, pottery distributions around centres of differing sizes. Do sites around major centres show a gradual fall-off in pottery frequencies, what is the structure of this fall-off, and where is the boundary with neighbouring service areas? Geographers’ models such as the Intervening Opportunities Model (Haggett, 1965: 46) and Reilly’s breaking point formula (Hodder, 1974) can be used by the archaeologist to examine such patterning and regional variation from overall trends.

So far, fairly general constraints which may determine the form of pottery distributions have been discussed. It is very important to identify these general constraints because they have a basic and underlying effect on the spatial patterns. Models of the form described above can be used, with a stochastic process as their base and with the application of general specified constraints, to predict or simulate expected patterns. The expected patterns can then be used as a starting point for the search of other, more interesting constraints. The main type of aditional constraint to be considered here is a social boundary.

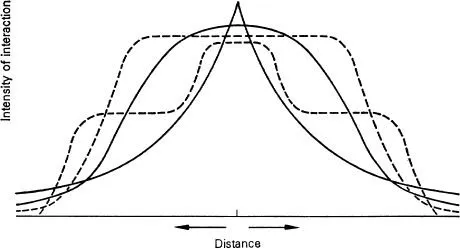

It has recently been suggested by several archaeologists (Sidrys, 1977; Ericson, 1977) that the presence of a social boundary hinders the movement of objects because there is less contact and interaction across the border. So it is claimed that kinks and plateaus occur in normally expected fall-off curves because of the greater and lesser interaction between and across social boundaries. For example, fig. 1 illustrates Soja’s (1971) suggestion that normal distance decay principles are distorted in cases where there is territorial behaviour.

Fig. 1. An illustration of Soja’s (1971) suggestion that normally expected fall-off curves (continuous lines) are distorted (broken lines) in areas with territorial behaviour.

Now, in fact, there is little anthropological evidence that the exchange of artifacts like pottery is hindered by social boundaries. Ericson (1977: 118) refers to Sahlins’ (1972) work which does, it is true, suggest that the nature of exchange may be different across and within social boundaries, but this does not necessarily mean that there is a smaller amount of exchange. In fact, in many cases exchange may be more intense across social boundaries, not less (Barth, 1969). Soja’s plateaus and kinks could not be expected as a result of variations in the amount of interaction and contact.

But this paper will show that Soja’s predictions would be expected for other reasons in certain conditions. Up to this point in the discussion, artifacts (pots) have been considered as having a value related to distance from source, cost of manufacture and so on. This is traditionally the geographer’s approach, where objects have a simple economic value related to time, effort and distance for example. But, at least in primitive societies (although also in our own), some, if not all, artifacts have another significance as well. This is that they can communicate information. As many anthropologists have pointed out (e.g. Leach, 1976), artifacts have a symbolic value which communicates information about the wearer, user or owner. For example, particular artifacts may be used to communicate that one belongs to a particular group (either a spatial group such as a tribe, sub-tribe or clan, or a hierarchical group such as a status group, age group or political group). In some cases, of course, societies and individuals may feel no need to express individual or group identities openly by the use of artifacts. In these instances deviation from the expected fall-off curves would not be found. But in other cases severe constraints may be imposed on groups and group membership. In these instances distinct deviations from expected fall-offs will occur if artifacts are used to indicate one group in opposition to another. It has to be made clear from the outset that it is not claimed that all groups express their identities in artifacts in this way. What is being claimed is that some may do in some circumstances and that the archaeologist has the evidence to identify social constraints and to examine why they should have been imposed. ‘Tribes’ do not equal ‘cultures’. But if they do not this does not mean that there is no point in looking at cultural distributions. On the contrary, it is contended here that there is a great mass of largely untapped information about human groups in artifact (such as pottery) distributions. But appropriate theory and method are needed before this information can be obtained.

An example will now be given in order to clarify the point made above, that the symbolic use of artifacts like pots contains potentially a large amount of information because it allows the archaeologist to identify where constraints in society are acting. The example derives from some ethnographic work carried out in Kenya. But it must be stressed that this is only an example. The theory and the approach do not depend on this particular ethnographic work. They may derive from it, but it is hoped that they have a logical structure which does not depend on the largely irrelevant ethnographic example which is given.

The fieldwork in the Baringo district of W. Kenya consisted of visiting over 400 hut compounds, recording information about the material culture of the inhabitants, and about their personal histories and relationships. The fieldwork procedure and the general results have been described elsewhere (Hodder, 1977b) and only the points salient to the present topic will be mentioned here.

The main tribal groups around Lake Baringo are the Njemps (immediately round the southern fringe of the lake), the Tugen (to their west, south and east), and the Pokot (to the north of the lake). Each tribe wears distinctive items of dress. Distributions of such items and,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- WHY POTTERY?

- POTTERY DISTRIBUTIONS: SERVICE AND TRIBAL AREAS

- AMBON-LEASE: A STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY POTTERY MAKING AND ITS ARCHAEOLOGICAL RELEVANCE

- AN APPROACH TO THE FUNCTIONAL INTERPRETATION OF POTTERY

- SERIATION PROBLEMS IN URBAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- DEALING WITH THE POTTERY FROM A 600 ACRE URBAN SITE

- CERAMIC PETROLOGY AND THE ARCHAEOLOGIST

- HOW MUCH POTTERY?

- MILITARY POTS, OR CALIBRATED ASSEMBLAGES?