eBook - ePub

Organizing Knowledge

An Introduction to Managing Access to Information

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organizing Knowledge

An Introduction to Managing Access to Information

About this book

The fourth edition of this standard student text, Organizing Knowledge, incorporates extensive revisions reflecting the increasing shift towards a networked and digital information environment, and its impact on documents, information, knowledge, users and managers. Offering a broad-based overview of the approaches and tools used in the structuring and dissemination of knowledge, it is written in an accessible style and well illustrated with figures and examples. The book has been structured into three parts and twelve chapters and has been thoroughly updated throughout. Part I discusses the nature, structuring and description of knowledge. Part II, with its five chapters, lies at the core of the book focusing as it does on access to information. Part III explores different types of knowledge organization systems and considers some of the management issues associated with such systems. Each chapter includes learning objectives, a chapter summary and a list of references for further reading. This is a key introductory text for undergraduate and postgraduate students of information management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organizing Knowledge by Jennifer Rowley,Richard Hartley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Library & Information Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Structuring and Describing

1 Knowledge, information and their organization

Introduction

In the knowledge-based society of the 21st century, data, information and knowledge are integral to our existence. Information and our ability to retrieve, select, evaluate, process and use it are pivotal to the survival and success of individuals, groups, organizations and communities. As quantities of information increase, means of organizing information so that it can be retrieved are becoming increasingly important. This introductory chapter sets the scene for more in-depth consideration of the tools and approaches in the organization of knowledge and information retrieval. At the end of this chapter you will:

- appreciate the need to organize knowledge

- have considered definitions of data, information and knowledge and the relationship between these

- be aware of the need for sophisticated and diverse tools for the organization of knowledge and information retrieval

- have considered some of the basic elements of the engagement of people and computers in the organization of knowledge and information retrieval

- appreciate some of the characteristics of knowledge that are important to its organization and use.

Why Organize Knowledge?

Knowledge is becoming ever more important to individuals, groups, organizations, communities, societies and nations. Compared with, say, 20 years ago individuals, organizations and communities experience:

- more information, communicated from

- a greater range of sources, through

- a wider range of channels, many of which have

- faster response and turnaround times.

Knowledge is viewed as an important, or arguably the most important asset. Knowledge and knowing is power. That power may bring political, social or economic success. Most developed countries are concerned to develop and capitalize on their knowledge assets to generate wealthier societies and economic growth. In order to achieve this they focus on both the development of learning environments (schools, colleges, universities, workplaces, virtual learning environments) and the development of, and networked access to, knowledge resources. This central significance of knowledge means that it is important that a user has convenient and appropriate access to the best information or knowledge at the right time, and in the most appropriate format. In order to make this possible it is necessary to organize knowledge. The organization of knowledge is the other face of information retrieval. The better organized that knowledge is, the easier it is to retrieve specific items of knowledge.

The overriding objective of the organization knowledge is the retrieval of information, hence the title of this book. We visit the distinction between information and knowledge below, but here we treat the two terms as synonymous. So, in principle it is necessary to organize things (books, DVDs, database records, the products sold by a supermarket and displayed on its shelves, paper files in filing cabinets and information on a website) in order to be able to find and locate, or retrieve, that required information easily. Organization of concepts is at the core of learning. Babies start their learning by organizing things into basic categories such as ‘faces’ or ‘things to eat’. As they grow, children develop their collection of categories and the number of items grouped into those categories. We learn by analysing and organizing data, information and knowledge.

Information and knowledge is also used for a wide range of other purposes, including:

- decision making

- problem solving

- communication and interpersonal relationships

- entertainment and leisure

- citizenship

- enhancing business and professional effectiveness, performance and success.

All of these processes benefit from access to appropriately organized information and knowledge.

This all sounds straightforward and intuitive – why, then, is the organization of knowledge so complex? Later in this chapter, we answer this question through two different routes: first, by considering the limitations of a popular information retrieval tool, the widely used search engine Google, and secondly, by considering the elements in the process of organizing and retrieving knowledge, and the contexts in which this occurs. But first we start with some definitions of information and knowledge.

Defining ‘Information’ and ‘Knowledge’

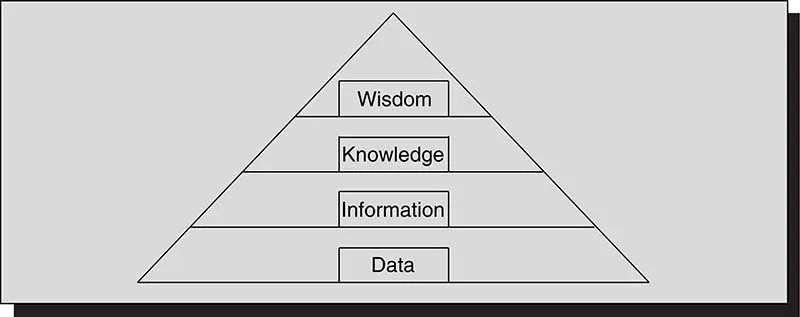

What is this entity, knowledge, that is to be organized, and how does it relate to the notion of information? There are a number of different ways to approach a discussion of the nature of information and knowledge. One of the useful starting points is to examine the DIKW hierarchy shown in Figure 1.1, which defines information in terms of data, knowledge in terms of information, and wisdom in terms of knowledge.

Figure 1.1 The DIKW hierarchy

In proposing this hierarchy, Ackoff (1989) offers the following definitions of data, information, knowledge and wisdom, and their associated transformation processes:

- Data is defined as a symbol that represents a property of an object, an event or of their environment. It is the product of observation but is of no use until it is in a usable (that is, relevant) form. The difference between data and information is functional, not structural.

- Information is contained in descriptions, answers to questions that begin with such words as ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘when’ and ‘how many’. Information systems generate, store, retrieve and process data. Information is inferred from data.

- Knowledge is know-how, and is what makes possible the transformation of information into instruction. Knowledge can be obtained either by transmission from another who has it, by instruction, or by extracting it from experience.

- Wisdom is the ability to increase effectiveness. Wisdom adds value, which requires the mental function that we call judgement. The ethical and aesthetic values that this implies are inherent to the actor and are unique and personal.

More recently, Rowley (2006) summarizes definitions in a number of textbooks, and proposes the following definitions of data, information and knowledge. Embedded in these definitions are implicit statements about the relationship between data, information and knowledge.

- Data can be characterized as being discrete, objective facts or observations, which are unorganized and unprocessed and therefore have no meaning or value because of the lack of context and interpretation.

- Information is described as organized or structured data, which has been processed in such as way that the information now has relevance for a specific purpose or context, and is therefore meaningful, valuable, useful and relevant.

- Knowledge is generally agreed to be an elusive concept which is difficult to define. Knowledge is typically defined with reference to information. For example the processes that convert information into knowledge are variously described as:– synthesis of multiple sources of information over time– belief structuring– study and experience– organization and processing to convey understanding, experience, accumulated learning and experience– internalization with reference to cognitive frameworks.

Other authors discuss the ‘added ingredients’ necessary to convert information into knowledge and suggest variously that knowledge is:

- a mix of contextual information, values, experience and rules

- information, expert opinion, skills and experience

- information combined with understanding and capability

- perception, skills, training, common sense and experience.

These various perspectives all take as their point of departure the relationship between data, information and knowledge. This tight coupling between these concepts means that organizations, communities and nations need to integrate the management of data, information and knowledge, and that more specifically the organization of knowledge is likely to involve the organization of data and information.

The knowledge management literature (for example Nonaka and Takuchi, 1995) identifies two different types of knowledge: explicit knowledge and implicit or tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge, or know-how, refers to personal knowledge embedded in the human mind through individual experience and involving intangible factors such as personal belief, perspective and values. Explicit knowledge, on the other hand, is knowledge that is codified and recorded in books, documents, reports, White Papers, spreadsheets, memos and other documents so that it can be shared. Tacit knowledge may be converted into explicit, objective or public knowledge through public expression such as speech, writing or the creation of images or performances. Some information scientists would argue that explicit knowledge is the same thing as information (Wilson, 2002; Taylor, 2004a). For example, Taylor (2004a, p. 2) argues that ‘it seems to me that I can use my knowledge to write a book, but until you read that book, understand it, and integrate it into your knowledge it is just information’. This comment reflects the essential feature of knowledge, which is that it involves understanding. There would appear to be an ongoing debate on whether explicit knowledge can be described as knowledge or is better described as information. However this debate is resolved, this book is concerned with the organization of explicit knowledge. The debate on the relationship between knowledge and information does serve to emphasize the tight coupling between the two. Certainly the process of searching and retrieval involves cognition and knowledge of both the subject or items being sought and the search process, and it could be said that as the searcher pulls together information resources as part of a search he or she ‘organizes knowledge’. In addition, if the term ‘explicit knowledge’ is used, the indexing and organization of packages of information or documents can be described as the organization of knowledge.

Published in 1987, the first edition of this book by the present authors was titled The Organization of Knowledge and Information Retrieval. Perhaps this wording might be seen as an attempt to have it all ways! In fact it followed in the tradition of earlier versions of the book which covered similar subject matter, written by another author working in the 1960s and 1970s.

Why Isn’t Google Sufficient?

People who have grown up and been educated with the rich resources available through the Internet, networked learning and information environments are inclined to the belief that if an Internet search engine, such as Google, cannot satisfy all of their information needs on the entry of a keyword or two, it can certainly take a very significant step in that direction. Google is becoming an indispensable aid to modern living and studying, to such an extent that in popular parlance it has generated the verb ‘to google’. Quite apart from the fact that such a transition is a major commercial achievement for any brand, such an accessible route to a diverse collection of information resources predisposes users to believe that knowledge is organized for them, and little effort is required in the organization of knowledge or information retrieval on their part. Google is a very powerful retrieval tool, and in its universality has achieved scope and coverage only dreamt of by the founders of information retrieval, with their visions of ‘universal bibliographic control’. Arguably even more significantly, Google has achieved a position as one of the leading global brands in a very short period of time. When previously has a tool that does no more and no less than offer an information search facility achieved such an elevated brand reputation and such significant global business success?

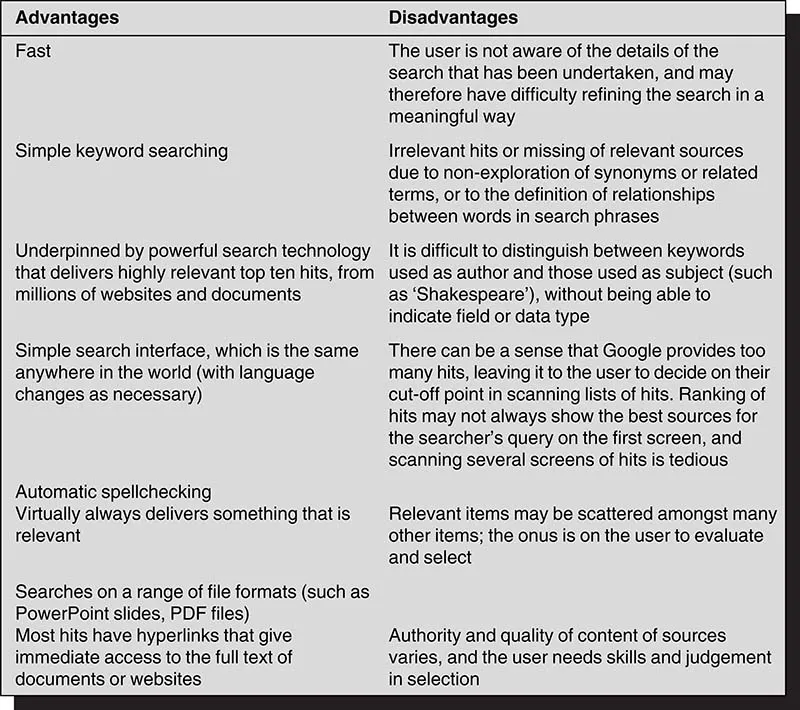

Figure 1.2 Evaluating Google

If Google were indeed the be-all and end-all for information retrieval, then this book would need to go no further than possibly explaining some of the more sophisticated search features offered by Google, and how to design optimum Google search strategies for different kinds of searches. Unfortunately, things are not that simple, and Google is only one tool in an armoury of different approaches to information retrieval. Figure 1.2 summarizes some of the advantages and disadvantages of Google as an information retrieval tool. The disadvantages identified lead into the wider debate as to what an information retrieval tool should do. On the other hand, it is important to note that the pre-eminence of Google as a first port of call derives from advantages such as its speed, ubiquity and convenience, which are characteristics that should be firmly placed at the forefront of the design of other information retrieval systems.

Tools for Organizing Knowledge and Information Retrieval

What happens to information? The greater part by far of information stored in the brain is discarded after immediate use. The time of day is important only for planning some subsequent action; the phase of a set of traffic lights serves only the immediate purpose of crossing the road or proceeding across a junction. We do not record this information, or retain it in our long-term memory. Some background information we do retain in long-term memory because we need to use it frequently: how to tell the time, or to proceed on green – this is part of our personal knowledge base. In between, there is information that we may possibly need to re-use at some future date or time, and this we record in personal information files. At...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acclaim for the third edition

- Contents

- List of figures

- Dedication

- Introduction

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- Part I Structuring and Describing

- Part II Access

- Part III Systems

- Index