![]()

1

Introduction

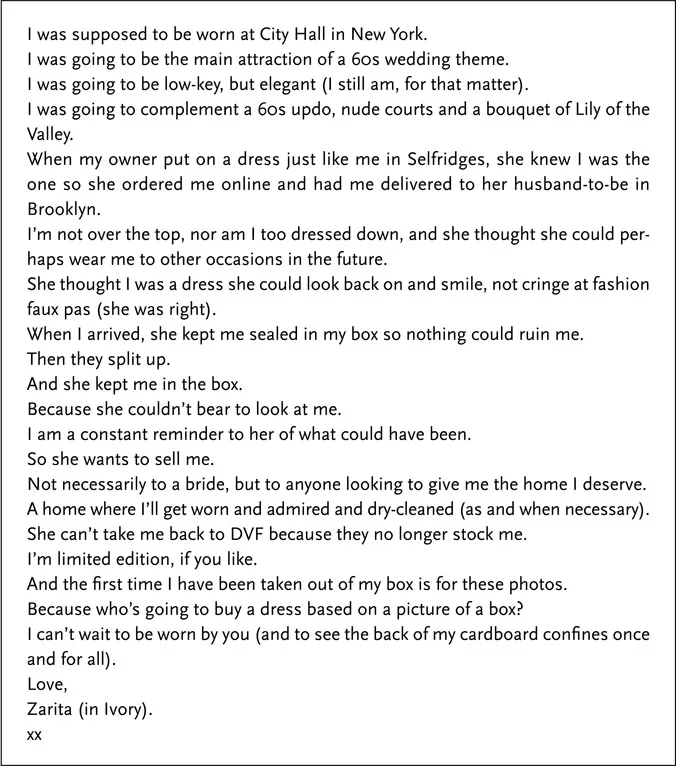

In June 2015, the following text – an advertisement for a wedding dress – was posted on the site of the popular e-retailer, eBay. Rather than providing a straightforward product description about the object for sale, the text presented readers with a rather unexpected narrative. What is perhaps most unusual about this text is the animation of an inanimate object, whose voice tells us the sad tale of being jilted before a wedding. In a surprising twist, the first-person-narrator’s voice that is represented here is that of one very depressed wedding dress.

As an audience who has just read this story, we might start by asking ourselves: What exactly is going on with this text? And why would its author choose to write it in this manner – and from this rather peculiar perspective? After all, most of us would probably agree that eBay product descriptions are normally written from the perspective of the human seller, and not from the perspective of the object that is for sale. (Plus, we all know very well that inanimate objects, like dresses, are incapable of writing.) As I will argue throughout this book, texts such as these can be viewed as acts of everyday linguistic creativity. And, as we will see, similar acts of linguistic creativity can be found in many different online contexts today. In crafting such texts, authors use language intentionally, skilfully, and we might even say “artfully,” as they introduce some unexpected, incongruous, and (strictly speaking) unnecessary elements into their writing. Very often, this type of linguistic creativity involves playing with different voices, as we can see in the above example, where the wedding dress is given a voice in the form of the story’s first-person narrator, and as, conversely, the dress’s human owner (and the actual author of the text) is reduced to merely a secondary character in the story.

Example 1.1 Wedding dress narrative (eBay)

But why engage in such language play, especially when it is not required in order to achieve the author’s practical goal of selling an item on an e-commerce platform? In this case, a straightforward product description is really all that is needed to make potential buyers aware that this dress, which has never been worn, is available for online purchase. One possible answer to this question is that creative language use such as this draws attention to itself. And in doing so, it simultaneously draws attention away from other, more pedestrian-sounding texts. Most digital environments today are replete with scores of texts and images that compete for our attention. Some scholars even use the term “attention economy” to refer to how, in content-rich online environments, human attention has become a very scarce commodity (e.g., Goldhaber, 1997). As media scholar Limor Shifman (2014) explains, “The most valuable resource in the information era is not information but the attention people pay to it” (p. 32). This means that providing a text like this with some unexpected twist – especially in an information-dense digital context like eBay – is one way of making a seller’s product stand out from dozens of otherwise similar products.

Originally posted on eBay in 2015 by a 30-year-old British woman, who wished to remain anonymous, this wedding dress advertisement was reproduced approximately one week later in a story about it in an online newspaper.1 The very fact that the advertisement captured a journalist’s attention enough to be taken from its original online context (eBay) and later recirculated in a different online context (Huffington Post) – through a process that linguists and media scholars call “recontextualization” – indicates that there must be something quite special about this text. It is also worth pointing out that the creativity in this example is not accomplished so much through formal elements (although you may have noticed a bit of repetition in the opening lines: “I was going to …”). Instead, creativity here is primarily achieved through a kind of role-playing in the unexpected crafting of the eBay advertisement as though it were written by the dress in the form of a letter. Another interesting feature of this text is how the dress, as the letter’s ostensible author, makes several appeals to readers’ emotions. Indeed, the title of the Huffington Post article calls it “The World’s Most Depressing eBay Listing.”

In the pages that follow, I will explore the different ways that individuals use language in order to craft online texts that are creative or humorous, and often both. Admittedly, these central concepts – creativity and humour – are both highly abstract and highly subjective. It is well known that a particular text, performance, or artefact that one person considers to be creative or funny, another person may find to be boring, uninteresting, or even offensive. However, what makes these topics particularly interesting to study in digital environments – especially on various social media platforms – is that these platforms usually provide a means for other users to signal their appreciation (or lack thereof) of the texts that have been posted there. In other words, social media provide users with affordances for engaging with, or reacting to, a text, in the form of comments, likes, reposts, reblogs, retweets, shares, upvotes, downvotes, and so on. Admittedly, these digital records of user reactions to a text cannot capture all the nuances of an individual’s response to what s/he has read or viewed. However, they can at least provide us with an overall indication of the extent to which others have found that text worthy of further attention or interaction. I will return to this idea of audience reactions at various points later in the book.

But first, let me present the contents of the rest of this chapter. The following section provides a brief overview of how creativity and humour have been theorized by various language scholars. This overview is then followed by a discussion of “voicing”: this is the central theoretical concept that guides all of my analyses of linguistic creativity and humour presented in subsequent chapters. After that, I illustrate what I mean by voicing, as I present an analysis of a Twitter interaction between a celebrity and one of her followers. Chapter 1 concludes with a brief preview of the book’s remaining chapters.

Linguistic Creativity

When many of us think of creative people, we probably imagine famous artists or great writers – in other words, the kinds of people who produce masterpieces. However, over the last few decades, a growing number of scholars in the humanities and social sciences have argued that creativity is not just something that characterizes great artists, but that it is actually part of our basic human nature. Where language is concerned, on some fundamental level, it can be said that each and every time we combine a set of words in a novel or unexpected way, we are being creative users of language. Experts on linguistic creativity, such as Ron Carter and Rodney Jones, make the point that creativity is not just the property of the artistic genius or the master wordsmith, but rather, that all competent humans have the capacity to be creative with language. In a nutshell, as linguists Carter and McCarthy (2004) explain, creative language use “is not a capacity of special people but a special capacity of all people” (p. 83, emphasis mine).

Most of us engage in some form of linguistic creativity on a regular basis. Carter (2016) calls this “everyday creativity,” and he offers several examples of this, such as making puns or playing with extended metaphors in everyday conversation. If we think about exchanging witty banter with a friend or family member, or viewing something amusing that appears on the digital screens in front of us, we actually do not have to look too far to find such instances of creative language use that surround us on a daily basis. This contemporary view of linguistic creativity also stresses that creativity is a social, rather than a psychological, phenomenon. In other words, rather than being an internal quality, which is the unique possession of an individual, creativity is something that is shared and co-constructed. As Jones (2016b) explains, studying linguistic creativity involves paying attention to how “language is used in situated social contexts to create new kinds of social identities and social practices” (p. 62). So, taking the wedding dress narrative as an example, we might say that the author produced a creative text by deviating from what is normally expected from the existing genre of eBay product descriptions. Instead, this eBay author chose to engage in a different kind of social practice in that particular online space, and this practice involved playfully giving a voice to an inanimate object.

There are also, of course, various degrees of creativity involving language use. For this reason, Carter (2016) introduced the notion of a “cline of creativity” (p. 67), meaning that it can be useful to conceptualize linguistic creativity as existing on a cline, or a continuum. On one end, we would find more literary forms of creativity (for instance, great works of literature or poetry). Whereas on the other end, we would find more everyday forms of creativity, such as some of the playful ways in which we use language in our daily interactions – or what we might consider vernacular forms of self-expression. So where would the above text (i.e., the wedding dress text) fall on this continuum of linguistic creativity? This is an intriguing question, and one which I will return to in the conclusion of this book. In the meantime, however, I would suggest that this is a useful question to ask ourselves each time that we encounter a text we consider creative.

Language scholars have identified several linguistic features commonly associated with creativity in everyday speech. These include “verbal repetition as well as a wide range of ‘figures of speech’ such as metaphor, simile, metonymy, idiom, slang expressions, proverbs, hyperbole” (Carter & McCarthy, 2004, p. 63), as well as “rhyme, rhythm, alliteration, wordplay, evocative metaphor” (Jaworski, 2016, p. 322). At the same time, these scholars caution against taking a strictly formal view of linguistic creativity, instead urging us to take a discourse approach. A discourse approach goes beyond the identification of these kinds of formal features of language, by also considering the functions, or the purposes, that such features may serve in discourse. This is important because not all instances of the abovementioned “creative features” will be considered creative by the participants who are involved in the interactions where they occur; in some cases, they may be considered quite unremarkable, or perhaps even go unnoticed. So, we might say that whether something is evaluated as creative, or not, ultimately lies in the eye of the beholder(s). Yet, it is also important to bear in mind that there may be a wide range of interpretations of any given text: especially when we think about texts found in online environments. These are important considerations, and for exactly these reasons, the digital texts that I have selected for inclusion in this book are those which have received some type of recognition, or signals of appreciation, from other internet users. In other words, I did not just select random examples that I thought were creative or funny, but instead, I selected texts that had been identified, in various ways, by other internet users as somehow remarkable.

As mentioned, a discourse approach involves not only identifying formal features of language, but also taking into account the various functions that linguistic creativity can serve. Previous scholarship has pointed out that linguistic creativity can be used to: contribute to humour or entertainment (more on this in the section below), emphasize a particular point being made, communicate a type of stance (either positive or negative), express a particular type of identity, mark topic boundaries, or construct a sense of mutuality (Carter & McCarthy, 2004). Often a single instance of linguistic creativity serves several of these functions simultaneously. These discourse functions have been derived from research examining linguistic creativity in spoken interactions, yet they are also relevant when it comes to communication in digital contexts. Finally, as will become evident in the later chapters of the book, many instances of linguistic creativity found in social media begin with a previously existing idea, text, or object, and add to it some kind of a novel, surprising, or unexpected twist. It could be said that creativity usually involves a tension between the known and the unknown – in other words, some kind of transformation of some existing thing, which is already familiar, or recognizable, to us. As I will show, linguistic creativity in online environments often involves new variations on some given, existing theme(s). Discourse analyst Michael Toolan (2012) offers several expressions that refer to this blending of old and new elements, which characterizes creativity: “hybridity,” “repetition with variation,” “norm- or habit-breaking” as well as “deautomatisation” (or “a making strange of the familiar”) (p. 18–22).

Taking a discourse approach, as I do in this book, means considering “how all the features of a text […] work together to form an effective whole, and further, how this whole interacts with the social context in which it is situated” (Jones, 2012, p. 6). This requires looking for patterns in the data as well as identifying similarities across individual texts. It also requires an understanding of how texts relate to their contexts, both their immediate contexts (i.e., the platforms on which they appear), as well as how they “interact with broader social formations and systems of values” (Jones, 2012, p. 9).

Humour and Language

Much of the existing scholarship on humour has tended to focus on conversational data. Moreover, it turns out that researchers of verbal humour have tended to actually focus much more on laughter than on humour (Attardo, 2015). This is largely due to the relative ease of objectively identifying laughter, in contrast to the greater subjectivity involved in deciding whether an utterance is humorous or not. Of course, not all laughter is a reaction to something funny (for instance, nervous laughter). Conversely, a strict focus on laughter as a signal of something humorous cannot capture instances of “failed” humour, or any attempt at humour that does not receive the hoped-for response. In sum, studying humour is notoriously tricky and involves several challenges, not the least of which is defining it, and determining what exactly “counts” as humour. But this has not stopped linguists from trying to gain a better understanding of the mechanics of humour.

Generally speaking, theories of verbal humour usually emphasize “script opposition” as one of the main principles at work in the creation of humour. Basically, a “script” refers to a specific domain of meaning and all of the words associated with it (Raskin, 1985). Furthermore, these scripts are both constituted by, and constitutive of, social norms. Script opposition happens when an utterance is compatible with two separate scripts that oppose each other (Attardo, 1994; Taylor & Raskin, 2012), and when the social norms underlying one of these scripts are defied (Tayebi, 2016). This accounts for how humour is created.

Now focussing on the other side of communicative interaction (i.e., the humour recipient), cognitive linguists who study the processing, or interpretation, of humour often invoke the notion of “incongruity resolution.” For instance, when a Twitter user crafts a message incorporating two (or more) elements that usually do not “belong” together (i.e., script opposition), this often helps to clue readers in to the fact that the intent of the message is humorous, and that it is not intended to be interpreted literally. As humour researchers Alamán and Rueda (2016) explain further, often it is this juxtaposition of two incongruous elements that invites readers to “recognize this contrast and activate a process of inference, which must lead to the recognition of the non-serious attitude of the speaker and the interpretation of the (implied) humoristic sense of the message” (p. 41). In other words, to understand that any message is funny, our minds must be able to resolve the incongruity that has just been presented to us in two somehow opposing social scripts.

If the identification of humour in conversational interactions is challenging, that challenge may even be further magnified in online contexts, where we typically do not have access to those paralinguistic cues that often function as acknowledgements of humour in face-to-face conversation (e.g., laughter, smiles, facial expressions, etc.). Yet most interactive online contexts have their own built-in affordances for signalling acknowledgement of humour. And while it may be even more difficult to determine if someone is trying to be funny online, the appreciation of “successful” humour in online discourse is frequently signalled in various ways, such as: laughter tokens (e.g., lol, hahahaha), metalinguistic comments (Hilarious!!, I’m still laughing like crazy), and other forms of appreciation (such as repetition, or imitation, of the humorous element), which can be found in comments from other users. Appreciation may also be indicated by a range of possible user “responsive uptake activities” (Varis & Blommaert, 2015, p. 35), such as the liking, upvoting, reblogging, retweeting, sharing, and so on that I mentioned earlier.

Just as I have pointed out that there are lists of formal features commonly associated with creative language, linguists have also found there to be certain formal elements that tend to appear in humorous language. For instance, discourse features such as polysemy (playing with different meanings ...