Dona Locke, Megan E. Denham, David J. Williamson, and Daniel Drane

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) may be the most extensively documented and investigated of the somatoform disorders, with a publication history dating back at least to the early Greeks (Gates, 2000). Uniquely among somatoform symptoms, PNES can be diagnosed with near 100% certainty due to the gold standard technique of video-EEG. Nevertheless, significant clinical roles persist for the neuropsychologist who works with this population. As neuropsychologists, we can contribute to the differential diagnosis and psychological case formulation based on behavioral and psychological data. We can help determine whether the cognitive complaints of the patient and/or family represent genuine impairment and/or transient effects of medication, psychological processes (e.g., cogniform disorder, effects of anxiety), or outright deception. Critically, we can integrate cognitive and psychological data to make decisions about disability and determine need or neurologic rehabilitation or psychological intervention. Moreover, when the comprehensive evaluation results in a diagnosis of PNES, we can help patients and families understand what happens next regarding the treatment of their PNES events and why.

We will present three clinical cases to walk the reader through our thinking on these issues. Along the way, we will describe not only what we find significant but the literature underlying these opinions. We will note the tests, procedures, and concepts we find most useful and the conclusions that we draw from them. Identifying details have been changed to protect identities, and some clinical details may be altered to highlight specific points that we believe to be most relevant. We readily acknowledge that there are other important scenarios, equally useful tests, and alternative, well-founded viewpoints that will not be described here. However, we hope to leave the reader with some perspectives, ideas, and ways of thinking about data that will enhance the care provided to patients and/or foster hypotheses to be examined that will enhance the knowledge available to fellow clinicians.

Video-EEG remains the clear diagnostic gold standard for differentiating epilepsy from PNES. However, the literature shows that details about a patient’s spell semiology, medical history, and personality can support diagnostic confidence as well as provide a psychological formulation for the development of PNES in that particular patient. In this way, neuropsychology is crucial to helping the treatment team, family, and patient understand the factors that led to the development and persistence of a psychogenic disorder for this patient. In this respect we are partnering with our physician colleagues who say, “You have psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, which are a form of psychological disorder. I am sure of this because your EEG is normal during your typical spell and we have ruled out cardiac, blood sugar, or autonomic explanation for your events as well.” Our experience is that, talented though our neurology colleagues may be, they prefer to leave the psychological formulation for WHY this particular patient developed PNES to us, along with their ultimate management. Some cases are more or less clear, and most theoretical models of PNES etiology suggest a complex system of predisposing factors, personality/adjustment profile, and recent stressors (Williamson, Ogden, & Drane, 2014). However, it has been our experience that we can improve the likelihood that a patient will accept the diagnosis and engage in psychiatric care with a two-pronged approach: (1) a caring but honest provision of the diagnosis by the neurologist based on the medical work up which is (2) supported by a preliminary psychological formulation of the patient based on comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation.

Case Study #1

Clinical History

Mr. Jones comes for neuropsychological evaluation due to seizure-like events that began approximately five years prior after having mononucleosis. Mr. Jones is in his thirties, right-handed, and married. He describes a dizzy or lightheaded feeling progressing to left-side twitching and stiffening. At times, he only feels “spacey” during the events, but at other times he experiences complete loss of awareness. These spells last perhaps 20 seconds, and he can feel fairly fatigued for about an hour afterward. He is having these episodes approximately twice per month. He has tried adequate doses of at least four antiepileptic medications.

In addition to seizure-like spells, Mr. Jones reported problems with migraines as well as general aches and pains all over. Outside physicians have suggested a diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Cognitively, he complained of difficulty concentrating for about one day after an episode, but otherwise denied significant cognitive concerns. His mother, who accompanied him to the assessment, reported that she felt his memory had worsened. She gave examples such as difficulty remembering details of their recent conversations. He denied any problems remembering to take his medications or keeping track of his appointments. He and his wife handle their finances separately, and he denied any problems with this. He denied any concerns by supervisors or co-workers about his work performance but acknowledged concern that he may miss a day of work because of his spells. He drives but was cautioned by his original evaluating neurologist regarding safety issues related to driving. His mother and wife step in for transportation when he is feeling poorly.

Developmental history is notable for a “traumatic birth” at term with a few days in the ICU before going home. Subsequent developmental milestones were met within normal limits, and he denied any learning or attention difficulties in school. He denied a history of developmental abuse, but reported that his parents’ divorce was very traumatic for him. Mr. Jones was in elementary school at the time, and they went to some family counseling. Neurologic history is significant for a sports-related concussion in high school from which he made a full recovery. He completed 2 years of college. He has been employed as a dealer in a casino for 12 years.

Mr. Jones has a history of gambling addiction and has been involved in Gambler’s Anonymous for 3 years. He denied any history of substance abuse. He is a lifelong nonsmoker and drinks one caffeinated beverage per day. He and his wife do not have any children, and he noted some recent discord in the marriage.

Comment

There are features of this patient’s demographic and medical history that both raise and lower suspicion for psychogenic spells. For example, this patient is male, whereas the majority of PNES cases are female (Cragar, Berry, Fakhoury, Cibula, & Schmitt, 2002; LaFrance, Baker, Duncan, Goldstein, & Reuber, 2013). His spells are short in duration with a primarily motor semiology, which could potentially suggest epilepsy and specifically frontal lobe focality (Cragar et al., 2002; LaFrance et al., 2013). His event frequency of twice per month could be consistent with epilepsy (LaFrance et al., 2013). On the other hand, his symptoms began in his twenties, which is consistent with typical onset of PNES. He has a history of possible fibromyalgia, which has been correlated with PNES (Benbadis, 2005). He denied a history of childhood abuse, but he reported significant trauma with his parents’ divorce, which could represent possible antecedent trauma (LaFrance et al., 2013). The only possible stressor the patient reported proximal to the beginning of his psychogenic spells was illness with mononucleosis. He denied other proximal psychosocial stressors.

Evaluation

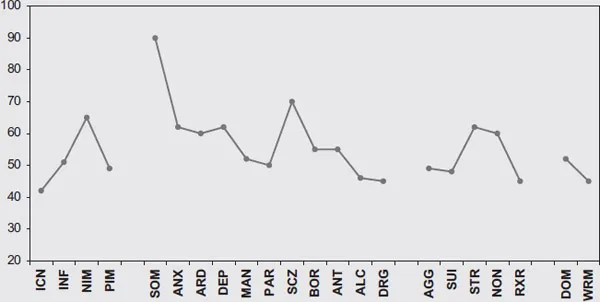

The patient was seen for comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation. The numerical results of that battery are presented in Table 5.1 and the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) profile is represented in Figure 5.1. As can be seen, the cognitive results are largely normal, with scores in the average or better range on all measures despite some mild memory complaints. On the PAI, however, the patient shows a significant elevation on the Somatic Complaints scale with a T-score of 90. Recent work has demonstrated that a T-score of 90 shows only 14%–19% sensitivity to PNES, but very high specificity (99%–100%) (Locke et al., 2011; Purdom et al., 2012).

Table 5.1 Test results for Case #1 Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III |

VIQ = 99 | PIQ = 104 | FSIQ = 101 | |

VCI = 98 | POI = 101 | WMI = 106 | PSI = 99 |

VOC = 10 | PC = 8 | ARITH = 12 | CODE = 11 |

SIM = 8 | BD = 11 | DSP = 9 | SS = 9 |

INFO = 11 | MR = 12 | LNS = 12 | |

Wechsler Memory Scale-III (scaled scores)

Logical Memory Immediate = 11

Logical Memory Delay = 13

Percent Retention = 14

Auditory Verbal Learning Test (T-scores)

Total Learning = 53

Short Delayed Recall = 64

Long Delayed Recall = 60

Brief Visual Memory Test-Revised (T-scores)

Total Learning = 57

Delayed Recall = 56

Rey-Complex Figure (T-scores)

Copy = 46

Immediate = 48

Delay = 50

Wide Range Achievement Test-4, Reading Recognition Standard Score = 97

Boston Naming Test (T-score) = 46

Controlled Oral Word Association (T-score) = 52

Animal Naming (T-score) = 64

Trailmaking (T-scores)

Part A = 60

Part B = 59

Stroop (T-scores)

Word = 49

Color = 53

Color-Word = 62

Finger Tapping (T-scores)

Dominant = 46

Nondominant = 45

Figure 5.1 Personality Assessment Inventory Profile for Case #1

It is worth noting here that we do not advocate the PAI or other personality inventory as necessarily “diagnostic” of psychogenic seizures. We agree with the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) consensus statement that states, “only ictal EEG can be used to differentiate PNES from epilepsy definitively at the individual level” (LaFrance et al., 2013, p. 2009). However, we disagree with their opinion that personality profiles are unlikely to contribute any diagnostic certainty. Sensitivity and specificity data can be used to ultimately calculate a posttest probability of the disorder of interest. In our setting, the pretest probability of PNES (based on the base rate in our setting) is approximately 38%. In this case scenario, 19% sensitivity and 99% specificity translate to a likelihood ratio of 12.75 (Purdom et al., 2012). Using that likelihood ratio and the 38% base rate for PNES in our setting, the posttest probability of PNES in the setting of a PAI Somatic Complaints scale of 90 is increased to 82%. Granted, this is not 100% certainty, but the PAI does provide increased certainty over the pretest probability just given the base rate. In addition, the personality assessments provide additional data on comorbid psychological functioning, such as the presence of significant mood and anxiety symptoms. In this case, the patient is reporting cognitive complaints (SCZ-T subscale) but overall is not reporting clinically significant depressive or anxiety symptoms.

In this case, we utilized the PAI as the personality assessment measure, but there is also ample research on the MMPI-2 and the beginnings of research data on the MMPI-2-RF in PNES. Derry and McLachlan (1996) developed classification rules for the MMPI-2 resulting in a PNES prediction with the following criteria: (1) a T-score on Scale 1 (Hs) and/or Scale 3 (Hy) greater than or equal to 65, (2) Scale 1 or 3 appearing in the 2-point code type, and (3) if 1 or 3 was not the highest scale, it must be within 6 T-score points of the highest (Derry & McLachlan, 1996). In their sample, they correctly classified 92% of PNES cases as well as 94% of epilepsy patients (LR = 15.3). Later cross-validation studies have shown lower classification rates for these rules with likelihood ratios ranging from 1.04 to 2.11 (Cragar et al., 2003; Locke et al., 2010; Locke & Thomas, 2011).

The MMPI-2-RF has some significant clinical scale revisions requiring new research in PNES. In a large vEEG-diagnosed sample of retrospectively rescored MMPI-2-RFs from the MMPI-2s, Locke et al. (2010) provide sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratio values for a range of scores on Restructured Clinical Scale 1 (RC1) and Neurologic Complaints (NUC) as well as the validity scale FBS-r, as these scaled scores showed the largest effect sizes in diagnostic group comparisons. For example, on RC1, LRs range from 1.89 at a T-score of 65 to 4.51 at a T-score of 90. Of note, with the significant changes to Restructured Clinical Scale 3 (RC3), the dual elevation of Scales 1 and 3 traditionally observed on the MMPI-2 is no longer present on the MMPI-2-RF.

Other Diagnostic Testing

In this case, the patient experienced a total of three typical events during the video-EEG admission. ...