eBook - ePub

Forensic Anthropology

A Comprehensive Introduction, Second Edition

- 446 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Forensic Anthropology

A Comprehensive Introduction, Second Edition

About this book

This robust, dynamic, and international field has grown to include interdisciplinary research, continually improving methodology, and globalization of training. Reflecting the diverse nature of the science from experts who have shaped it, Forensic Anthropology: A Comprehensive Introduction Second Edition builds off of the success of the first edition and incorporates standard practices in addition to cutting-edge approaches in a user-friendly format, making it an ideal introductory-level text.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Forensic Anthropology by Natalie R. Langley,MariaTeresa A. Tersigni-Tarrant, Natalie R. Langley, MariaTeresa A. Tersigni-Tarrant in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Forensic Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION III

Skeletal Individuation and Analyses

8 Sex Estimation of Unknown Human Skeletal Remains

9 Ancestry Estimation: The Importance, The History, and The Practice

10 Age Estimation Methods

11 Stature Estimation

12 Pathological Conditions as Individuating Traits in a Forensic Context

13 Analysis of Skeletal Trauma

14 Introduction to Fordisc 3 and Human Variation Statistics

CHAPTER 8

Sex Estimation of Unknown Human Skeletal Remains

CONTENTS

Introduction

Sex versus gender

Sexual dimorphism

DNA

Documentation

Morphological approaches to sex determination

Pelvis

Skull

Other postcranial bones

Metric approaches to sex determination

Population-specific standards

When methods disagree

Conclusion

Summary

Review questions

Acknowledgments

Glossary

References

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Explain the difference between sex and gender.

2. Explain the difference between metric and morphological/nonmetric techniques for determining sex from skeletal remains.

3. Define and describe human sexual dimorphism (i.e., when it develops and why it is relevant to sex determination).

4. Discuss best practices in sex determination.

5. List the bony elements that forensic anthropologists frequently use to determine sex in the order of accuracy (most to least accurate), and name several methods for each element.

6. Explain the concept of a sectioning point, and discuss factors that influence sectioning points.

7. Name the variables that should be taken into account when determining sex from the skeleton, and explain how these variables might affect one’s assessment.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter explores the approaches and methods used to determine sex from the human skeleton. Skeletal sex determination in medico-legal or archaeological context is a key component of personal identification and for establishing the remainder of the biological profile. Sexing methods are typically divided into two categories: morphological (shape) and metric (size). Morphological aspects of the human skeleton that are sex-specific are found primarily in the pelvis and, less so, in the other bones of the body. Metric differences between the sexes are mainly found in the skull but also in the postcranial skeleton. Both categories have varying accuracy rates, with the pelvis being the best indicator overall; however, some metric methods are accurate >90% of the time. This chapter details several morphological techniques and provides a discussion of the statistical aspects of metric sex determination. As with any rigorous science, a solid foundation in basic techniques is necessary, and that foundation is the goal of this chapter.

SEX VERSUS GENDER

Two specific terms are frequently confused in common usage: sex and gender. This is a major issue in science, because the difference between these words is a distinction between a biological reality and a social category. For scientists, sex is a biological fact, whereas gender is a socially ascribed and perceived identity. The confusion may stem from several sources: it could be because the general public lacks the awareness of the distinction between the two terms, and perhaps, from the common usage of gender on governmental and business forms when, in fact, sex is meant. Overall, the confusion likely lies in the fact that most people believe these words to be synonyms, when they are not. As anthropologists, we can only determine the biological sex of an individual from skeletal remains, not that individual’s gender, character, or role. In some cases, gender might be implied from examining the material culture found in conjunction with skeletal remains such as clothing, jewelry, weaponry, and class symbols, but this determination can be very difficult and is fraught with uncertainty. We must remember that when a police investigator asks for the gender of an unknown decedent, it is not a question of how that individual dressed, acted, or performed various roles in society but rather a simple question of biologically male or female. We should be mindful of how we apply these terms in everyday professional discussions, casework, or publications, so that we do not perpetuate this misconception.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

When an anthropologist is asked to determine the sex of an individual, he or she always starts with 50/50 odds of being correct, as there are only two biological states: male and female. In order to increase the odds of accuracy, the anthropologist needs to understand sexual dimorphism. Sexual dimorphism generally refers to size and shape differences between males and females of a given species, although other differences in anatomy, function, behavior, and psychology are present. In many ways, this statement oversimplifies the definition; however, for purposes of this chapter, it functions as a basis for the discussion on sexing skeletal remains. Easily seen soft tissue differences between the sexes are not the only physical manifestation of sexual dimorphism; the hard tissues of the skeleton are also affected. In some species, the differences are extremely marked, but in others, only subtle differences exist. For the skeletal system, size is often the most dramatic and easily observed disparity between males and females. For instance, given a selection of 25 male and 25 female gorilla skulls mixed together, an untrained observer could place the skulls into a contiguous line, from males to females, solely based on size and would likely be 100% correct. Given the same scenario for human skulls, the untrained observer may achieve a 60% correct classification based on size, if lucky, and where the males and females meet in the middle of the chain would be very hard to determine. This is because humans are not as sexually dimorphic as gorillas—human sexual dimorphism is less pronounced and often population-specific.

Skeletally, sexual dimorphism develops with the onset of sexual hormone production around the time of puberty; these hormones control and regulate the expression of the secondary sexual characteristics. As would be expected in most human populations, these changes are better defined nearing the age of 17 years; however, they can be present much earlier in developmentally precocious individuals. Therefore, estimation of sex from the skeleton is easier in adults and late adolescents and is much harder in subadults. Most anthropologists would argue that sexing individuals younger than 15 years results in an educated guess; however, techniques are available. The accuracy of these techniques depends on the preservation of the skeletal elements, the population from which they are originated, and whether known-sex comparative specimens from that same population are available. The Scientific Working Group for Forensic Anthropology (SWGANTH) has specifically weighed in on this topic. The SWGANTH is a joint venture between the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Defense Central Identification Laboratory that develops consensus best-practice forensic anthropology guidelines and establishes minimum standards. In addition, the committee disseminates the guidelines, studies, and findings from their meetings at http://www.swganth.org/index.html. For subadult sex determination, the SWGANTH states that sexing individuals younger than 12 years is an unacceptable practice; however, results may be achieved if the pelvis is fusing and methods for adults are applied to the remains (that are older than 14 years) (SWGANTH 2010, p. 3). Other good reviews of the challenges, techniques, and pitfalls for subadult sex estimation can be found in Komar and Buikstra (2007) and Scheuer and Black (2000).

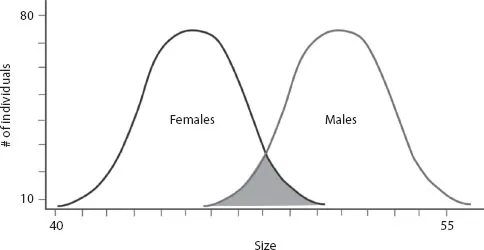

Figure 8.1 Two even 20% overlapping bell curves. The gray-shaded area where the curves overlap is an ambiguous zone in which misidentifications occur. (Courtesy of J. Hefner.)

For the most part, sexual dimorphism in the human skeleton can be stated as “males are larger and more robust than females, or females are smaller and more gracile than males.” A favorite saying is that males are usually bigger than females. Males can be upward of 20%–30% larger than females in certain skeletal dimensions (e.g., the size of the femoral and humeral heads). However, individual variation can make this general rule hard to follow—as with any bell curve, some individuals are much larger or smaller than the average. Given two even, 20% overlapping bell curves, the area where the curves overlap is where misidentification happens (Figure 8.1). Said differently, small, gracile males can be easily confused with large, robust females. Complicating the picture, human populations vary across time and geographic space. As a simple example, populations with life ways focused on hunting and gathering frequently tend to produce large and rugose individuals, whereas individuals in sedentary populations are often less rugose and potentially smaller owing to less stress placed on skeletal tissues. If a hunter/gatherer female is compared with a sedentary male, it is quite possible to confuse the sexes of these two individuals based on size and rugosity, and vice versa. This example is not meant to factor in all of the biological complexities that surround this issue; rather, it is a simple explanation of a complex problem. For these reasons, anthropologists must examine as much skeletal data as possible before assigning sex to an unknown individual, and population- and period-specific standards should be used for each case. Familiarity with the individual variation within a population can alleviate some problems. If one is not familiar with the range of variation, seriating the population (creating a series from largest to smallest) can be a good practical exercise to become accustomed to a population’s variation.

DNA

Scientific advances may someday make sex determination easier for the anthropologist. The state of molecular technology (DNA testing) is such that a simple test for the presence or absence of a Y chromosome can determine sex from skeletal remains. This is particularly helpful in cases involving juvenile remains. Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on your view), DNA testing is not cheap, and for large skeletal assemblages, it is cost-prohibitive. The time required for DNA tests is frequently several weeks to several months, versus a determination by the anthropologist, which can be made in a matter of minutes. Furthermore, DNA analysis requires destruction of bone, and acquiring the necessary permissions for testing in archaeological contexts can be very difficult. These limiting factors will dictate the need of anthropologists to determine sex of most unidentified individuals for the foreseeable future. That stated, it behooves the cautious anthropologist to seek out DNA testing in medico-legal cases involving juvenile remains, where this is a feasible option.

DOCUMENTATION

Perhaps, the most important aspect of an anthropologist’s work is the documentation of the procedures, methods, and interpretations made in the course of a skeletal analysis. Proper scientific documentation is the backbone of a thorough analysis. Each SWGANTH document expressly indicates that relevant tests, observations, exemplars, and decision-making processes are documented as part of a case file. A standardized notes packet is helpful in this regard. For sex determination, good documentation includes a comprehensive skeletal inventory, notes on the condition of the remains, the age of the remains (both skeletally and temporally), details of any pathological conditions or deleterious processes that have affected the remains, and any con...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Editors

- Contributors

- SECTION I Forensic Anthropology and the Crime Scene

- SECTION II The Skeleton and Skeletal Documentation

- SECTION III Skeletal Individuation and Analyses

- SECTION IV Human Identification and Advanced Forensic Anthropology Applications

- Appendix A: Application of Dentition in Forensic Anthropology

- Appendix B: Age Estimation in Modern Forensic Anthropology

- Glossary

- Index