Dependable, Embedded Software

This is a book about the development of dependable, embedded software.

It is traditional to begin books and articles about embedded software with the statistic of how many more lines of embedded code there are in a modern motor car than in a modern airliner. It is traditional to start books and articles about dependable code with a homily about the penalties of finding bugs late in the development process — the well-known exponential cost curve.

What inhibits me from this approach is that I have read Laurent Bossavit’s wonderful book, The Leprechauns of Software Engineering (reference [1]), which ruthlessly investigates such “well-known” software engineering preconceptions and exposes their lack of foundation.

In particular, Bossavit points out the circular logic associated with the exponential cost of finding and fixing bugs later in the development process: “Software engineering is a social process, not a naturally occurring one — it therefore has the property that what we believe about software engineering has causal impacts on what is real about software engineering.” Because we expect it to be more expensive to fix bugs later in the development process, we have created procedures that make it more expensive.

Bossavit’s observation is important and will be invoked several times in this book because I hope to shake your faith in other “leprechauns” associated with embedded software.

Safety Culture

A safety culture is a culture that allows the boss to hear bad news.

Sidney Dekker

Most of this book addresses the technical aspects of building a product that can be certified to a standard, such as IEC 61508 or ISO 26262. There is one additional, critically important aspect of building a product that could affect public safety — the responsibilities carried by the individual designers, implementers and verification engineers. It is easy to read the safety standards mechanically, and treat their requirements as hoops through which the project has to jump, but those standards were written to be read by people working within a safety culture.

Annex B of ISO 26262-2 provides a list of examples indicative of good or poor safety cultures, including “groupthink” (bad), intellectual diversity within the team (good), and a culture of identifying and disclosing potential risks to safety (good). Everyone concerned with the development of a safety-critical device needs to be aware that human life may hang on the quality of the design and implementation.

Anecdote 1 I first started to think about the safety-critical aspects of a design in the late 1980s when I was managing the development of a piece of telecommunications equipment.

A programmer, reading the code at his desk, realized that a safety check in our product could be bypassed. The system was designed in such a way that, when a technician was working on the equipment, a high-voltage test was carried out on the external line as a safety measure. If a high voltage was present, the software refused to close the relays that connected the technician’s equipment to the line.

The fault found by the programmer allowed the high-voltage check to be omitted under very unusual conditions.

I was under significant pressure from my management to ship the product. It was pointed out that high voltages rarely were present and, even if they were, it was only under very unusual circumstances that the check would be skipped.

I now realize that, at that time, I had none of the techniques described in this book for assessing the situation and making a reasoned and justifiable decision. It was this incident that set me off down the road that has led to this book.

The official inquiry into the Deepwater Horizon tragedy (reference [2]) specifically addresses the safety culture within the oil and gas industry: “The immediate causes of the Macondo well blowout can be traced to a series of identifiable mistakes made by BP, Halliburton, and Transocean that reveal such systematic failures in risk management that they place in doubt the safety culture of the entire industry.”

The term “safety culture” appears 116 times in the official Nimrod Review (reference [3]) following the investigation into the crash of the Nimrod aircraft XV230 in 2006. In particular, the review includes a whole chapter describing what is required of a safety culture and explicitly states that “The shortcomings in the current airworthiness system in the MOD are manifold and include . . . a Safety Culture that has allowed ‘business’ to eclipse Airworthiness.”

In a healthy safety culture, any developer working on a safety-critical product has the right to know how to assess a risk, and has the duty to bring safety considerations forward.

As Les Chambers said in his blog in February 2012* when commenting on the Deepwater Horizon tragedy:

We have an ethical duty to come out of our mathematical sandboxes and take more social responsibility for the systems we build — even if this means career threatening conflict with a powerful boss. Knowledge is the traditional currency of engineering, but we must also deal in belief.

One other question that Chambers addresses in that blog posting is whether it is acceptable to pass a decision “upwards.” In the incident described in Anecdote 1, I refused to sign the release documentation and passed the decision to my boss. Would that have absolved me morally or legally from any guilt in the matter, had the equipment been shipped and had an injury resulted? In fact, my boss also refused to sign and shipment was delayed at great expense.

I am reminded of an anecdote told at a conference on safety-critical systems that I attended a few years back. One of the delegates said that he had a friend who was a lawyer. This lawyer quite often defended engineers who had been accused of developing a defective product that had caused serious injury or death. Apparently, the lawyer was usually confident that he could get the engineer proven innocent if the case came to court. But in many cases the case never came to court because the engineer had committed suicide. This anecdote killed the conversation as we all reflected on its implications for each of us personally.

Our Path

I have structured this book as follows:

Background material.

Chapter 2 introduces some of the terminology to be found later in the book. This is important because words such as fault, error, and failure, often used almost interchangeably in everyday life, have much sharper meanings when discussing embedded systems.

A device to be used in a safety-critical application will be developed in accordance with the requirements of an international standard. Reference [4] by John McDermid and Andrew Rae points out that there are several hundred standards related to safety engineering.

From this smörgåsbord, I have chosen a small number for discussion in Chapter 3, in particular IEC 61508, which relates to industrial systems and forms the foundation for many other standards; ISO 26262 which extends and specializes IEC 61508 for systems within cars; and IEC 62304, which covers software in medical devices.

I also mention other standards, for example, IEC 29119, the software testing standard, and EN 50128, the railway standard, to support my arguments here and there in the text.

To make some of the discussion more concrete, in Chapter 4 I introduce two fictitious companies. One of these is producing a device for sale into a safety-critical market, and the other is providing a component for that device. This allows me to illustrate how these two companies might work together within the framework of the standards.

Developing a product for a safety-critical application.

Chapter 5 describes the analyses that are carried out for any such development — a hazard and risk analysis, the safety case analysis, the failure analysis, etc. — and Chapter 6 discusses the problems associated with incorporating external (possibly third-party) components into a safety-critical device.

Techniques recommended in the standards.

Both IEC 61508 and ISO 26262 contain a large number of tables recommending various techniques to be applied during a software development. Many of these are commonly used in any software development (e.g., interface testing), but some are less well-known. Chapters 7 to 19 cover some of these less common techniques.

For convenience, I have divided these into patterns used during the architecture and design of a product (Chapters 7 to 10), the tools that are used to ensure the validity of the design (Chapters 11 to 15), the techniques used during implementation (Chapters 16 to 18), and those used during implementation verification (Chapter 19).

Development tools

One essential, but sometimes overlooked, task during a development is preparing evidence of the correct operation of the tools used; it is irrelevant whether or not the programmers are producing good code if the compiler is compiling it incorrectly. Chapter 20 provides some insights into how such evidence might be collected.

I introduce the goal structuring notation and Bayesian belief networks in Chapter 5, but relegate details about them to Appendices A and B respectively. Finally, there is a little mathematics here and there in this book. Appendix C describes the notations I have used.

Development Approach

There are many development methodologies ranging from pure waterfall (to which Bossavit dedicates an entire chapter and appendix in reference [1]) through modified waterfall, design-to-schedule, theory-W, joint application development, rapid application development, timebox development, rapid prototyping, agile development with SCRUM to eXtreme programming.

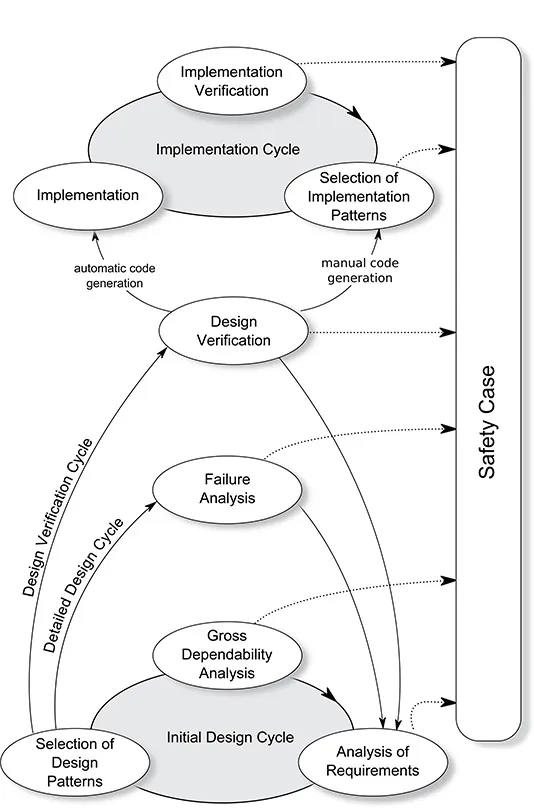

I do not wish to take sides in the debate about which of these techniques is the most appropriate for the development of an embedded system, and so, throughout this book, I will make use of the composite approach outlined in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The suggested approach.

During a development process, certain tasks have to be completed (although typically not sequentially):