Practical Management of Affective Disorders in Older People

A Multi-Professional Approach

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Practical Management of Affective Disorders in Older People

A Multi-Professional Approach

About this book

Building on the success of "Practical Psychiatry of Old Age" now in its Fourth Edition, this book looks in more detail at affective disorders from a variety of perspectives. It includes expert contributions on areas such as aetiology, diagnosis and psychological and pharmacological treatment. It also focuses on a contextual approach to the management of affective disorders in areas like primary care and geriatric medicine, as well as the specific contributions of disciplines such as nursing, social work and occupational therapy. User and carer viewpoints are also included, along with the often neglected spiritual aspects of managing these conditions. This balanced, inclusive and practical approach makes it ideal for all members of the multi-disciplinary team involved in the management of affective disorders in older people.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Affective disorders in the new millennium

Introduction

Depression

- associations with physical illness and disability/handicap

- exercise

- gender differences

- detection and measurement of outcome.

Clinical features

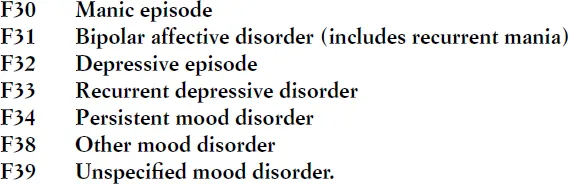

Classification and definitions

- The syndrome must be present for at least two weeks, there must be no history of mania/hypomania and the depression must not be attributable to organic disease or psychoactive substances (the difficulty of this will become evident when we examine associations with physical illness in more detail).

- At least two of the following three symptoms must be present:

- Depressed mood to a degree that is definitely abnormal for the individual, present for most of the day and for almost every day, and largely uninfluenced by circumstances

- Loss of interest or pleasure in activities that are normally pleasurable

- Decreased energy or increased fatiguability.

- Additional symptoms from the following list to give a total of at least four:

- Loss of confidence or self-esteem

- Unreasonable self-reproach or excessive and inappropriate guilt

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide; suicidal behaviour

- Complaints or evidence of diminished ability to think or concentrate, such as indecisiveness or vacillation

- Change in psychomotor activity with agitation or retardation (either subjective or objective)

- Sleep disturbance

- Change in appetite/weight.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- About the editors

- Contributor

- 1 Affective disorders in the new millennium

- 2 Affective disorders in old age: detection and clinical features

- 3 Aetiology of late-life affective disorders

- 4 Pharmacological management of depression in older people

- 5 Pharmacological treatment of bipolar affective disorder in old age

- 6 Electricity, magnetism and mood

- 7 Psychotherapy with older people

- 8 Depression in physically ill older patients

- 9 Relationship between physical illness and affective disorders

- 10 Depression in primary care

- 11 The role of the nurse in the assessment, diagnosis and management of patients with affective disorders

- 12 Occupational therapy and affective disorders

- 13 Social services for older people with depression

- 14 Carer and service user perspectives of affective disorders in older adults

- 15 Cultural aspects of affective disorders in older people

- 16 Religion/spirituality and depression in old age

- 17 An overview of human drug development

- Index