1.1 Background

Sensors dominate the world in which we live. We are awakened in the morning by an alarm clock and proceed to breakfast in our home, which has smoke detectors. Our breakfast is often prepared with the aid of timing devices, and temperature sensors tell us when the food is ready to eat. We then proceed to go to work in our automobile, which may have more than 50 different sensors helping in the operation and control of the vehicle. At our workplace we are surrounded by sensors that can be very simple, such as temperature and humidity sensors. Other workplace sensors are quite complex, such as sensors to detect potential explosives, metal objects, etc. If our work requires travel, then we encounter a wide spectrum of sensors in the detection of a variety of objects that may be on our person or in a suitcase.

In addition to sensors relating directly to the individual, a whole list of sensors exist on local, state, national, and global levels. For example, traffic signals in your town are often controlled by sensors. At the state level, a variety of sensors help us in terms of waste management and water quality. Sensors are present at a national level and are critical to the security of our homeland. On a global level, sensors exist to measure quantities such as ozone and pollutants that may be present in international waters.

In recent years, the complexity of advancing technology, the ever-increasing world population, and the emergence of terrorist-related activities have heightened the need for new types of sensors. Depending upon the particular application, the design, fabrication, testing, and eventual use of the sensors requires a wide variety of both technical and nontechnical expertise. As a result, sensors have become an emerging technology that prevails in the world in which we live.

1.2 The Human Body as a Sensor System

The human body serves as one of the best examples of a complex system that contains a wide variety of sensors capable of sensitively and selectively detecting a wide variety of quantities or measurands. The most familiar sensors in the human body are those that relate to vision, hearing, smell, taste, and feel.

The human eye can detect both small and large objects that may be stationary or in motion. The eye may also detect very subtle variations in color or shape. A classic example of this is the recognition of a human face. The recognition of a familiar face in a large crowd truly emphasizes the selectivity embodied in the vision system. The human vision system does, however, have a finite dynamic range, which is determined by the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum, namely, from wavelengths of 4,100 Å (violet) to 6,600 Å (red). This represents a frequency range from 7.32 × 1014 cycles per second (cps) to 4.55 × 1014 cps. Considering that the electromagnetic spectrum has a range of over 1020 cps, visible light represents a very small part of the spectrum.

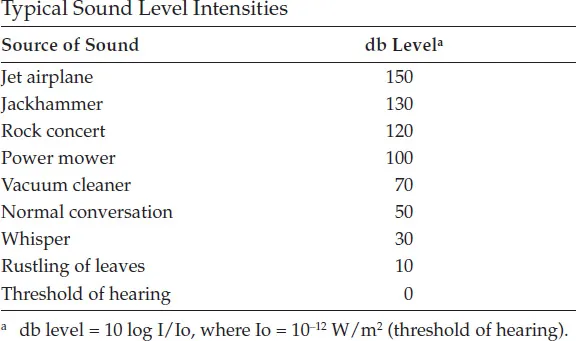

The human ear is an example of a very sensitive sensor with a limited dynamic range. In particular, the ear is capable of detecting sound levels as low as 10−12 Watts/m2 (0 db) and as high as 1 W/m2 (120 db), which is the threshold of pain. The frequency range for the ear is limited to 20 Hz to 20 kHz. This represents only a small portion of the sound wave spectrum, which covers a range of over 1013 Hz. It is well known that prolonged exposure to high-intensity sound levels may produce serious ear damage. In fact, noise pollution may contribute to anxiety, nervousness, and high blood pressure. Some typical sound level intensities are given in Table 1.1. Prolonged exposure to sound levels over 90 db is considered to be dangerous and ear protection is recommended. This clearly points out the need for sound intensity sensors, particularly in an industrial environment.

TABLE 1.1 Typical Sound Level Intensities

The human nose represents perhaps one of the most sensitive and selective sensors in the human body. The nose is capable of differentiating subtle differences in odor such as may occur in different types of wine. The nose can also detect various degrees of “freshness” that may occur in fish. The limits of sensitivity of the nose are in the low parts per billion (ppb) to the parts per million (ppm) level in air for a target gas. This sensitivity level is better than that of many of the best commercially available gas sensors.

Taste is not as sensitive or selective as the other familiar body sensors. Although differences in levels of sweetness, sourness, and saltiness can be detected in taste, people often confuse taste with odor. The true measure of the taste sensor may be experienced if one has a cold. In this case, the interference from odor is eliminated.

The so-called feel sensor is usually associated with the hand, but can in fact be located anywhere in the body. This sensor enables one to determine such physical features as an object’s size, shape, roughness, and weight. In recent years advances in robotics have resulted in the design and fabrication of artificial feel sensors, such as robotic arms, hands, and fingers, which have found widespread applications in industry.

In addition to the five common body sensors, other abstract sensors exist in the human body that can affect the individual in a variety of different ways. For example, the death of a loved one evokes a feeling of sadness in an individual. Danger often evokes excitement, and overcoming an obstacle may evoke pleasure or satisfaction.

Finally, the human body has a built-in defense or immune system that is often triggered by sensors different from those already discussed. For example, the invasion of the human body by antigens associated with a particular disease or infection triggers the formation of antibodies, which then fight the disease or infection.

The sensors within the human body, particularly the five principal sensors, can be looked upon as real-time control systems. It is essential that these control systems communicate accurately and effectively so the human body can avoid dangers and perform satisfactorily. Ideally, we would like our sensors to respond quickly, sensitively, and selectively to a particular measurand. However, with a degradation in sensor operating accuracy or function caused by factors such as misuse, age, or disease, it is then necessary to make certain modifications to restore the sensor performance. For example, deteriorating eyesight or hearing can be corrected with use of glasses or hearing aids. These corrective measures then simply appear in the feedback loop of the real-time control system associated with the sensor.

1.3 Sensors in an Automobile

In a real-world system, such as an automobile, the ability of an electronic control system to communicate accurately and effectively to the automobile operator is critical to the operation of the automobile. Since the automobile has to be operating in concert with an outside world of significant complexity, the need for reliable, effective, and accurate sensors is extremely high.

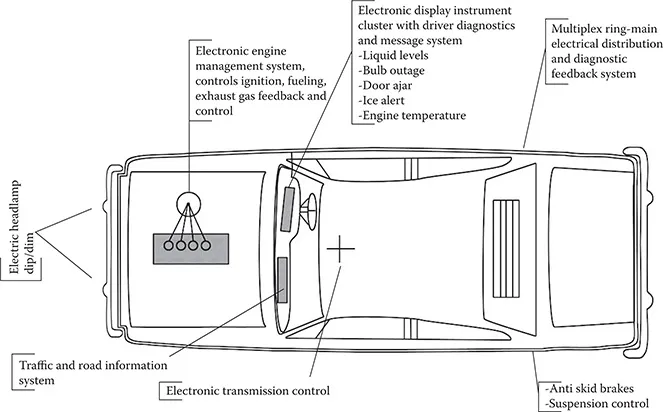

In order to appreciate the need, diversity, and complexity of sensors required in an automobile, it is interesting to briefly examine the systems in an automobile in which sensors are used. In Figure 1.1, several potential areas of the automobile in which sensors are used are highlighted. It can be seen that the sensor functions may range from a simple sensing of oil pressure, water temperature, and fuel level to the intensive control of the engine and transmission to optimize economy and performance while minimizing potentially dangerous emission effluents. In order to appreciate the exacting specification and complexity of some automobile sensors, it is interesting to examine the sensors appropriate for the engine and transmission, or what is commonly referred to as the power train. Various power train sensors and their required specifications are presented in Table 1.2. These sensors are critical to the automobile performance and relate to engine timing, manifold vacuum pressure and mass airflow, exhaust gas oxygen level, transmission control valve position, transmission input and output speed, and throttle and accelerator position. It can be seen that the requirements for parameters such as accuracy and operating temperature range are exacting. In addition to meeting technical specifications, these sensors must also meet space and weight requirements and be of minimal cost and high reliability. To discuss each of the power train sensors in detail requires background in such diverse areas as physics, chemistry, engineering, economics, and politics.

FIGURE 1.1 (Please see color insert following page 146) Areas where sensors can be utilized in the automobile. (From Westbrook, M. H., and Turner, J. D., Automotive Sensors, London: Institute of Physics Publishing, 1994, 9. With permission.)

TABLE 1.2 Optimized Specifications for Some Common Automotive Power Train Sensors

The multidisciplinary nature of sensors can best be illustrated by describing the development of gas sensors relating to the control of the combustion mixtures in car engines. The goal of these sensors is to decrease atmospheric pollution while increasing fuel economy. The initiative in developing the comb...