eBook - ePub

The Indigenous Dynamic in Taiwan's Postwar Development: Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship

Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Indigenous Dynamic in Taiwan's Postwar Development: Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship

Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship

About this book

Using Taiwan's third largest export industry - shoe manufacturing - as a case study, this work contends that economic development can be tied to Taiwan's own cultural history as well as to the influx of foreign capital or the initiatives of the state government.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Indigenous Dynamic in Taiwan's Postwar Development: Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship by Ian Skoggard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Negocios en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Negocios y empresaSubtopic

Negocios en general1

Beyond the Pale

Most accounts of the Taiwan Miracle are ahistorical, establishing as their baseline the years immediately following the Second World War.1 The intensive Allied bombing that destroyed much of Taiwan’s industrial and transportation infrastructure resulted in a postwar period of economic devastation (Selya 1974). Furthermore, the agrarian character of Taiwanese society of poor small-holding family farms was the legacy of fifty years of Japanese colonial rule, from 1895 to 1945 (Barclay 1954). The period of stasis under the Japanese and the years immediately following the Second World War contrast sharply with the dynamism of the later postwar period, and of the period before the Japanese occupation. Constructing a baseline with the arrival of the Nationalists in 1948 distorts the picture of Taiwan’s development, in which a sleepy agrarianism explodes into industrial vigor under the beneficence of the Nationalist government (Gates 1996). Moving the baseline back into history provides a new perspective on Taiwan’s development, connecting it to an earlier, formative period in the nation’s history. In this chapter, I examine the development of Taiwan’s social structure—and the tensions inherent in this structure—which I argue forms the basis of its postwar indigenous dynamic. In the following chapter, I will examine local religion as a locus of historical memory (Sangren 1987), wherein the unresolved contradictions of the past were transformed into religious practice and paraphernalia. The fierce countenance of the gods both evoked Taiwan’s terrible past and empowered the Taiwanese as they faced a rapidly changing and uncertain future.

This will not be a conventional history of Taiwan, but one that seeks to uncover the contradictions of frontier life and determine what made it so violent. The problem of land claims on the frontier, together with a lucrative market in grain and sugar, made Taiwan a volatile social field. Traditionally, the state relied on local structures of dominance to maintain social order. Until those structures emerged, it had little choice but to play one group against another and let a strong winner prevail, who was then coopted by the state. This was the essence of Chinese statecraft on the frontier (Shepherd 1993). The violence so prevalent during this period was crucial to the formation of stable social relations on the island, a prerequisite for full incorporation into the Imperial realm. Until that occurred, Taiwan was a land “beyond the pale.”

On the Margin

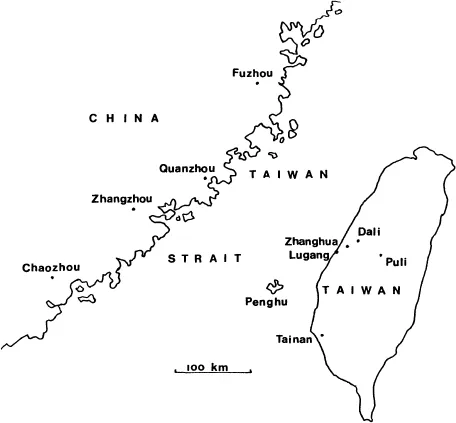

The roots of modern Taiwan lie in the global expansion of mercantilism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which incorporated China’s southeastern city ports into a vast trading diaspora, linking markets in South and Southeast Asia to those in the Middle East and Europe. In this period, the southern Fujian city of Zhangzhou, called “Little Soochow,” was one of the empire’s busiest and wealthiest ports, and communities in the surrounding hinterland were transformed into suppliers of commodities for regional and long-distance trade (Rawski 1972, 66). By the end of the seventeenth century Amoy, the “city of Silver,” became the richest city in South China, dominating the coastal trade from Tianjin to Guangzhou (Ng 1983).

The commercialization and urbanization of Fujian created a demand for rice that the local mountainous area could not satisfy. Although the long coastal plain of western Taiwan was ideal for paddy cultivation, hostile aborigines, the treacherous waters of the Taiwan Strait, and an unfavorable climate discouraged settlement. It was not until the Dutch built a fort near present-day Tainan in 1623 that a bridgehead for Han immigration was secured. Because they needed a source of food and revenue, the Dutch encouraged and sponsored the migration and settlement of Han farmers. By the end of the Dutch period, the Han population had grown to 35,000, and exports totalled 100,000 catties of sugar annually (Shepherd 1993, 86). After a thirty-eight-year occupation, the Dutch lost their most lucrative Asian trading post to a retreating band of Ming loyalists lead by Zheng Chenggong. Zheng and his son further promoted the island’s development and established military colonies along the coast and within the interior, to reclaim the land. Under the Zhengs, the Han population on the island increased to 120,000.

In 1683, this last Ming redoubt capitulated to Qing forces, who incorporated Taiwan into the empire as a prefecture of Fujian Province. The island received a greater flow of immigrants, who began to spread out and settle aboriginal territory. The government’s divide-and-rule policy was to separate the aborigines into two categories: “cooked” and “raw,” distinguishing those aborigines on the cusp of Han encroachment from those living beyond it. The land claims of the “cooked” aborigines were respected, but an earthen wall was built between reclaimed land and the territory of the “raw” aborigines, who were considered hostile and treated as outlaws. The wall would be moved further and further inland until it reached the foothills of Taiwan’s massive interior mountain range. By the end of the eighteenth century, the whole western coastal plain was settled, marking the close of the first period of Han settlement (Shepherd 1993).

The Qing dynasty (1644–1912) was a formative time in the island’s cultural, social, and political development. In this period, regional commercial interests and imperial political interests were in conflict over the island’s development. On the one side were Fujian gentry–merchants who had invested in the production of Taiwanese grain and sugar. On the other side was the Qing court, which believed that peace and harmony on the frontier lay in an undeveloped Taiwan and in respecting aboriginal interests and rights.2 The court feared that the provocation of the original inhabitants of Taiwan by Chinese settlers would be a source of endless trouble, which would be beyond their power to control and would lead to rebellion. It wanted to avoid both the cost of maintaining a large garrison on the island and the risk of inadvertently creating a strong rebel base there if the garrison proved insufficient and locals perceived the state to be weak. The Qing court, therefore, continued the embargo on migration to Taiwan and on trade between Taiwan and the mainland. It also recognized the inviolability of native land claims. However, neither of these policies did much to squelch the merchants’ desire for profit and the destitute migrants’ hope for a second chance in a new land (Shepherd 1993, 12–13).

The government’s immigration and land policy wavered back and forth. At first an embargo was placed on all shipping to Taiwan, restricting both trade and immigration. Trade and migration continued to be conducted clandestinely by coastal pirates, often in collusion with local gentry, merchants, and government officials, all of whose interests lay in the expansion of regional markets and trade (Beckmann 1973, 31–35). In 1683, the Qing opened communications slightly, allowing trade between Xiamen and Tainan, Taiwan’s southern port and first Han settlement. Only men were allowed to emigrate; women and children were forced to stay home as hostages in order to secure the loyalty of the immigrants. Many of the island’s immigrants were seasonal workers who returned home to the mainland each year. Several hundred thousand men would make the trip from Fujian and eastern Guangdong to Taiwan, where they would grow and harvest rice, sell it to the merchants who sponsored their trip, and then return home with a modicum of cash to support their families (Ho 1959, 164; Kuo, T. 1973). The ban on the immigration of women and children into Taiwan was permanently lifted only in 1760. In 1783, the Central Taiwan port, Lugang, was officially opened to the outside world (Shepherd 1993, 161–72).

In conjunction with the slackening of restrictions on immigration, native lands were opened to Chinese settlers for cultivation. Small family groups were lured to the island by government proclamations advertising the availability of “deer fields.” Once in Taiwan, both types of immigrants, small family groups and individual men, became dependent on nonkin associations for protection and promotion of their interests (Hsu 1980, 88). Collective muscle was required to reclaim the land, which involved leveling the ground and building irrigation channels to make paddies. The voluntary associations also provided safety in numbers and helped to enforce the rules of reciprocity between association members and between members of different associations.

Two types of local social organization developed on Taiwan in the eighteenth century, one based on blood relationships (xueyuan zuzhi) and the other on shared locale (diyuan zuzhi). The former included households, families, clans, clan associations, and ancestor organizations. The second type of social organization included public temple organizations and god associations (shenminghui). The two types of social organization could overlap, with kin-based groups forming the core of many territorial-based organizations. The latter were hierarchically arranged and corresponded to the sociopolitical units of neighborhoods, hamlets, villages, and towns. At the center of each unit was a temple. The ceremonies associated with each temple helped to validate inter- and intravillage social relations, demarcating the productive and commercial relationships that tied settlements together. The religious network of temples reflected the historical migration of the Han from the towns and villages of Fujian to Taiwanese ports and their hinterland (Cai 1976; Sangren 1987; Lin 1989).

The Land Patent System

The government managed the settlement process through a land patent system. Anyone who wanted to open land had to petition the local government; upon approval would receive a patent for perpetuity if he brought the land under cultivation within a ten-year reclamation period. The patent holder also had a three-year tax reprieve (Knapp 1980b, 60). The patent holders in most cases were not farmers but merchants or gentry, those who stood to benefit most from the local and regional trade in rice and sugarcane, and who had the official connections and the wealth to purchase the license, recruit labor, and provide workers with bread stakes, transportation, and tools (Meskill 1979, 47).

One patent holder, Shi Lumen, developed land on the Zhanghua plain of central Taiwan. Shi was born in Quanzhou Prefecture, Fujian Province in 1640. He made a fortune in the sugar trade between Taiwan and Japan, and at the age of fifty he decided to invest in land development on the Zhanghua Plain. Shi obtained a patent from the government and permission to construct an irrigation channel from the military governor of Fujian Province. Construction was begun in 1709 and completed in 1719 at a cost of 950,000 ounces of silver. The irrigation system provided water for the fields of eight of the thirteen villages extant in Zhanghua at the time and received a water rent of 2,650,000 kilograms of rice annually (Wang, D. 1972, 166–69).

Much labor was required to level land and construct irrigation systems to create paddies. The patent holder recruited peasant laborers from the mainland or the more populated southern part of the island. Patent holders had to offer the peasant laborers a more secure form of land tenure in order to attract farmers to do the initial reclamation work. The farmers were given surface rights, or the “skin of the field” (tianpi), while the patent holder retained the subsurface rights, or the “bones of the field” (tiangu). The patent holder became known as the “big-rent holder” (dazihu) and was responsible for paying taxes. The farmer, the small-rent holder (xiaozihu), held the right to rent his surface rights to another farmer, which created a three-tier land tenure system. The small-rent holder paid the patent holder a nominal annual fee—the big rent—whereas he received a much more substantial “small” rent from his tenants (Knapp 1980b, 61–63).

The ties between big- and small-rent holder became more obscure and tenuous, with the latter clearly in the most advantageous position (Knapp 1980b, 63; Cai 1976, 36). It was he who held the actual usufruct rights and who also benefited from the growing commerce in rice and sugar. Also, the small-rent holder became rooted in the thickening interactions of rural society and benefited from the ties of solidarity that grew out of such social intercourse. As the power of the small-rent holders grew, they were able to challenge the patent holders, whose ties with gentry, merchants, and government officials in the towns and on the mainland proved an insufficient deterrent. For government officials it was a delicate situation to mediate. Without the decisive power of the state to enforce the payment of the big rent, officials had to compromise or resort to playing one small-rent holder against another, one surname group against another, one ethnic group against another, creating cycles of internecine strife (Lamley 1981, 312).

From the beginning, Taiwan’s frontier society was highly commercialized and export-oriented (Shepherd 1993, 171). As mentioned above, the Dutch had first encouraged sugarcane cultivation and trade. It is estimated that by the 1720s, up to 60,000 metric tons of sugar was exported annually to Amoy, an amount that represented ten times the island’s own sugar consumption. Using 1742 data, Shepherd estimates that 23 percent of the island’s rice harvest was exported. The number of market towns increased from 21 in 1694 to 62 in 1740 and 137 in 1768, reflecting both increases in population, land reclamation, and trade. High prices in mainland markets stimulated land reclamation and settlement on Taiwan. Shepherd writes that “investors in reclamation projects could be ensured of profits in selling their rental income [in grain] in the lucrative Fujian markets” (ibid., 166).

The different gods worshipped on the island and the different dialects spoken reflected distinct subethnic groups, which could form the basis of political division. Nearly all of Taiwan’s settlers came from southern Fujian Province and eastern Guangdong Province, embarking through that region’s three major seaports. The two largest subethnic groups came from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou prefectures in Fujian Province. A third group were Hakka-speaking people from eastern Guangdong Province, who embarked from Chaozhou. The Quanzhou people were the first to settle Taiwan, occupying the coastal areas and comprising a majority of the island’s merchants and government officials. The later-arriving Zhangzhou people settled in the interior, where they took up farming. Tensions between state and local society and between merchants and producers were expressed in feuds among ethnic groups (Cai 1976). This internecine fighting fortified ethnic identities and divisions, as refugees sought protection within larger ethnic enclaves (Lin 1990). The merchant elite promoted religious and ethnic loyalty as part of a strategy to secure markets for the different trading interests that linked the island to mainland ports (Cai 1976, 38).

Developing Social Relations

In spite of the gods and the state, Taiwan’s frontier history was extremely violent. Insurrections and internecine conflicts erupted on the average of once every three years during the 212–year period under Qing rule (1663–1895). The saying “an uprising each three years, a rebellion every five” (Lamley 1981, 290) was not an exaggeration. A total of 68 revolts and 77 intergroup conflicts have been recorded. The scholar Hsu Wen-hsiung has divided the Qing period into three periods characterized by conflicts of varying intensity (see table 1).

The beginning and end of the intermediate period are the years of the two largest rebellions on Taiwan. Of the total of 68 revolts, 66 started in rural areas. In seven revolts county seats were taken, and in one rebels succeeded in capturing the capital, where the rebel leader crowned himself king and ruled for fifty days before he was ous...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Tables

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Beyond the Pale

- 2 Fragrant Rings

- 3 The Visible Hand

- 4 A Blessing From Heaven

- 5 Clicking, Closing, and Making

- 6 Local Heroes

- 7 Every Living Room a Factory

- 8 Inscribing Capitalism

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index