![]()

CHAPTER

1

LABORATORY MEDICINE—AN INTRODUCTION

IN THIS CHAPTER

PROCESS AND TERMINOLOGY

HOW DOES THE SYSTEM WORK?

USING FLUIDS TO ASSESS TISSUE DISEASE

PRE-ANALYTICAL FACTORS

WHAT CONSTITUTES AN ABNORMAL RESULT?

WHAT IS A REFERENCE RANGE?

AN IDEAL DIAGNOSTIC TEST

USING REFERENCE RANGES

HOW DOES CLINICAL CHEMISTRY OPERATE?

QUALITY ASSURANCE

QUALITY CONTROL

ACCREDITATION

From a somewhat humble beginning using rudimentary chemical and biological tests and microscope slides, laboratory medicine has progressed to become an essential component in the diagnosis and management of disease. It has evolved into a group of subspecialties which includes Histopathology or Cell Pathology, Hematology, Microbiology, Clinical Biochemistry or Clinical Chemistry, and Immunology and these disciplines have specialized further as new areas of science and technology have been adopted. For example, the techniques of molecular biology and genetics have been embraced by all disciplines leading to the development of separate departments in some institutions. In other institutions, however, such developments have prompted a rethink of working practices and the combination of aspects of hematology, immunology, and biochemistry into all-embracing departments of Blood Sciences or Clinical Laboratory Sciences. Throughout these changes, the principles of clinical biochemistry have remained constant, relating and adapting human biochemistry to the development of diagnosis and the management of disease.

Although terminology may vary between institutions, the terms Chemical Pathology, Clinical Chemistry, Medical Biochemistry, and Clinical Biochemistry are often used interchangeably; the term Clinical Chemistry will be used in this text. The clinical biochemistry of tissues, organs, and molecules is discussed in the context of disease processes and related to the diagnosis, monitoring, and management of disease. This will include outlining the fundamental metabolism of biochemical processes and physiological interrelationships. Some space has been given to descriptions of analytical processes and theory, such as immunoassay, and how these relate to clinical practice. Although the emphasis of this book is clinical biochemistry, some chapters include sections on hematology, radiology, and microbiology as appropriate only where this helps in the understanding of disease processes. However, it is not intended to provide the detail expected in specialized textbooks on these disciplines. The increasing use of the techniques of molecular biology and genetics in the investigation of disease is acknowledged also by appropriate inclusion of these disciplines in a number of chapters.

1.1 PROCESS AND TERMINOLOGY

Several general aspects of clinical biochemistry process and terminology are first defined to enable the reader to better understand subsequent chapters. Clinical chemistry laboratories are engaged in the analysis of tissue samples and the interpretation of data derived from these analyses. In doing so, they have a number of key functions:

- To help in the diagnosis, monitoring, and management of disease

- To screen populations for disease

- To assess risk factors for disease processes

- To engage in research and development of analytical and diagnostic tools

- To teach and train new staff

While this illustrates the scope of the work of major clinical biochemistry departments and each of the above functions is important per se, the fundamental role of clinical chemistry in most hospitals is in the diagnosis, monitoring, and management of disease.

For this textbook, Standard International (SI) units of measurement have been employed. For some tests, where non-SI units are in common use as well as SI units, both sets of units are quoted.

1.2 HOW DOES THE SYSTEM WORK?

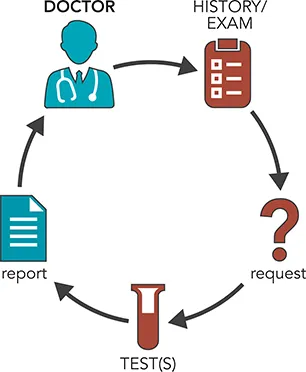

To illustrate the process, consider this simple scenario where a patient attends his family doctor complaining of tiredness (Figure 1.1). After first taking a short history, recording symptoms, and carrying out a physical examination, the doctor considers whether the patient might be anemic. The next step is to take a blood sample to determine whether the tiredness and any other symptoms, including looking pale, might be due to anemia; that is, to a low hemoglobin level (Figure 1.2). The blood sample is transferred to a (hospital) laboratory for analysis and interpretation, and a report is sent to the requesting doctor. The test for anemia is usually performed by Hematology or Combined Blood Science Departments as part of a full blood count (FBC) which assesses a number of blood cell parameters, including hemoglobin concentration. Usually, such analyses are undertaken using large automated cell counters (instruments). Where appropriate, some of the blood sample is examined under a microscope to determine blood cell morphology. For the patient above, the following results were found (Figure 1.3). The hemoglobin concentration of 97 g/L (9.7 g/dL) is clearly below the normal range of 130–180 g/L (13.0–18.0 g/dL) for an adult male and implies that the patient is anemic. A decreased concentration of hemoglobin lowers the capacity of the red cells to transport oxygen to the tissues throughout the body, giving rise to tiredness, and explains some of the patient’s symptoms. However, there are a number of different types of anemia (see Chapters 10 and 16) and further tests are required to ascertain which is present in this case.

Microscopic examination of the patient’s blood film (Figure 1.3c) indicates that the red cells of the patient have less color and are smaller than red cells from a healthy, adult male. In summary, the patient has small red cells lacking in pigmentation and a low hemoglobin content; that is, the patient has microcytic, hypochromic anemia. A common cause of this type of anemia is iron deficiency and further tests in the clinical biochemistry laboratory are required to investigate this.

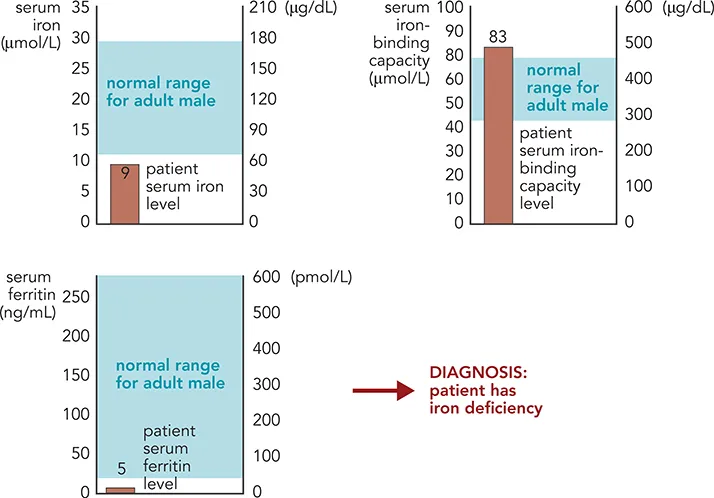

Although some clinical biochemistry analyses are made on whole blood, most tests have been developed on the supernatant fluid remaining after the blood cells have been separated by centrifugation. If blood is taken into a plain glass or plastic tube and the sample is allowed to clot, the resulting supernatant is termed serum. However, if an anticoagulant is added to the tube to prevent clotting, the supernatant liquid is termed plasma. Measurements assessing iron deficiency may be made on either serum or plasma. In the current scenario, the patient’s serum iron is indeed below the normal range for adult males (Figure 1.4), suggesting iron deficiency. This may be due to decreased intake into the body due to low dietary iron or malabsorption, increased loss through bleeding, or a combination of both. Further tests are required to investigate these possibilities. Iron is transported in the circulation bound to a protein, transferrin (see Chapter 10), and the amount of iron that can be bound to transferrin can be measured and expressed as total iron-binding capacity (TIBC). As a patient becomes progressively iron deficient, the liver synthesizes more transferrin, thereby increasing the TIBC, to maximize the amount of iron being absorbed from the gut and transported to the tissues. This response in itself is not specific for iron deficiency, so serum ferritin is routinely measured. Ferritin is a protein that can bind large amounts of iron and functions as an intracellular store of iron, particularly in liver and bone marrow. Small amounts of ferritin are released into the circulation during cell turnover and measurement of serum ferritin gives an indication of the iron stores in these tissues. The lower the serum ferritin level is, the lower the tissue ferritin stores and thus whole body iron stores. The results for the patient shown in Figure 1.4 indicate that all three additional parameters measured are below the normal range for adult males, confirming that the patient has iron deficiency. This is a diagnosis and helps to direct investigations into the cause of iron deficiency (see Chapter 10). Where possible, the underlying cause is treated and the patient is given iron supplements to return his iron and hemoglobin concentrations to within the normal range. Hematology and clinical biochemistry tests are used to monitor the effectiveness of treatment.

1.3 USING FLUIDS TO ASSESS TISSUE DISEASE

Although several diseases are due to abnormalities in the blood, for example abnormal red blood cells, most diseases are characterized by abnormalities in specific tissues. Since it is difficult to routinely take biopsy material from the affected tissue, blood and urine are frequently examined to show whether tissue damage or disease is present. Many compounds are released into th...