Chapter 1

Introduction to geotechnical engineering

1.1 What is geotechnical engineering?

The use of engineering soils and rocks in construction is older than history and no other materials, except timber, were used until about 200 years ago when an iron bridge was built by Abraham Darby in Coalbrookdale. Soils and rocks are still one of the most important construction materials used either in their natural state in foundations or excavations or recompacted in dams and embankments.

Engineering soils are mostly just broken up rock, which is sometimes decomposed into clay, so they are simply collections of particles. Dry sand will pour like water but it will form a cone, and you can make a sandcastle and measure its compressive strength as you would a concrete cylinder. Clay behaves more like plasticine or butter. If the clay has a high water content it squashes like warm butter, but if it has a low water content it is brittle like cold butter and it will fracture and crack. The mechanics that govern the stability of a small excavation or a small slope and the bearing capacity of boots in soft mud are exactly the same as for large excavations and foundations.

Many engineers were first introduced to civil engineering as children building structures with Meccano or Lego or with sticks and string. They also discovered the behaviour of water and soil. They built sandcastles and they found it was impossible to dig a hole in the beach below the water table. At home they played with sand and plasticine. Many of these childhood experiences provide the experimental evidence for theories and practices in structures, hydraulics and soil mechanics. I have suggested some simple experiments which you can try at home. These will illustrate the basic behaviour of soils and how foundations and excavations work. As you work through the book I will explain your observations and use these to illustrate some important geotechnical engineering theories and analyses.

In the ground soils are usually saturated so the void spaces between the grains are filled with water. Rocks are really strongly cemented soils but they are often cracked and jointed so they are like soil in which the grains fit very closely together. Natural soils and rocks appear in other disciplines such as agriculture and mining, but in these cases their biological and chemical properties are more important than their mechanical properties. Soils are granular materials and principles of soil mechanics are relevant to storage and transportation of other granular materials such as mineral ores and grain.

Figure 1.1 illustrates a range of geotechnical structures. Except for the foundations, the retaining walls and the tunnel lining all are made from natural geological materials. In slopes and retaining walls the soils apply the loads as well as provide strength and stiffness. Geotechnical engineering is simply the branch of engineering that deals with structures built of, or in, natural soils and rocks. The subject requires knowledge of strength and stiffness of soils and rocks, methods of analyses of structures and hydraulics of groundwater flow.

Figure 1.1 Examples of geotechnical engineering construction.

Use of natural soil and rock makes geotechnical engineering different from many other branches of engineering and more interesting. The distinction is that most engineers can select and specify the materials they use, but geotechnical engineers must use the materials that exist in the ground and they have only very limited possibilities for improving their properties. This means that an essential part of geotechnical engineering is a ground investigation to determine what materials are present and what their properties are. Since soils and rocks were formed by natural geological processes, knowledge of geology is essential for geotechnical engineering.

1.2 Principles of engineering

Engineers design a very wide variety of systems, machines and structures from car engines to very large bridges. A car engine has many moving parts and a number of mechanisms, such as the pistons, connecting rods and crankshaft or the camshaft and valves, while a bridge should not move very much and it certainly should not form a mechanism. Other branches of engineering are concerned with the production and supply of energy, the manufacture of washing machines and personal computers, the supply, removal and cleaning of water, moving vehicles and goods and so on.

Within civil engineering the major technical divisions are structural (bridges and buildings), hydraulic (moving water) and geotechnical (foundations and excavations). These are all broadly similar in the sense that a material, such as steel, water or soil, in a structure, such as a bridge, river or foundation, is loaded and moves about. The fundamental principles of structural, hydraulic and geotechnical engineering are also broadly similar and follow the same fundamental laws of mechanics. It is a pity that these subjects are often taught separately so that the essential links between them are lost.

In each case materials are used to make systems or structures or machines and engineers use theories and do calculations that demonstrate that these will work properly; bridges must not fall down, slopes or foundations must not fail and nor must they move very much. These theories must say something about the strength, stiffness and flow of the materials and the way the whole structure works. They will investigate ultimate limit states to demonstrate that the structure does not fall down and they will also investigate serviceability limit states to show that the movements are acceptable.

Notice that engineers do not themselves build or repair things; they design them and supervise their construction by workers. There is a common popular misconception about the role of engineers. The general public often believes that engineers build things. They do not; engineers design things and workmen build them under the direction of engineers. Engineers are really applied scientists, and very skilled and inventive ones.

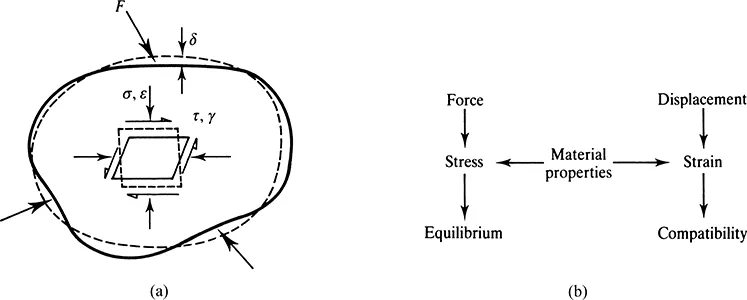

1.3 Fundamentals of mechanics

In any body, framework or mechanism, changes of loads cause movements; for example a rubber band stretches if you pull it, a tall building sways in the wind and pedalling a bicycle turns the wheels. The basic feature of any system of forces and displacements and stresses and strains are illustrated in Fig. 1.2. Forces give rise to stresses and these must be in equilibrium or the body will accelerate. Displacements give rise to strains which must be compatible so the material does not tear or overlap. (Relationships between forces and stresses and between displacements and strains are given in Chapter 2.) These two separate requirements (of equilibrium and compatibility) are quite simple and they apply universally to everything. The relationships between stresses and strains (or between forces and displacements) are governed by the characteristics of the material.

Figure 1.2 Principles of mechanics.

There are a number of branches or subdivisions of mechanics which depend on the material, the type of problem and any assumptions made. Obviously soil mechanics is the mechanics of structures made of soils and there are also rock mechanics for rocks and fluid mechanics for fluids. Some important branches of mechanics are illustrated in Fig. 1.3; all of these are used in soil mechanics and appear later in this book.

Rigid body mechanics deals with mechanisms, such as car engines, in which all the moving parts are assumed to be rigid and do not deform. Structural mechanics is for framed structures where deformations arise largely from bending of beams and columns. Fluid mechanics is concerned with the flow of fluids through pipes and channels or past wings, and there are various branches depending on whether the fluid is compressible or not. Continuum mechanics deals with stresses and strains throughout a deforming body made up of material that is continuous (i.e. it does not have any cracks or joints or identifiable features), while particulate mechanics synthesizes the overall behaviour of a particulate material from the response of the individual grains. You might think that particulate mechanics would be relevant to soils but most of current soil mechanics and geotechnical engineering is continuum mechanics or rigid body mechanics.

1.4 Material behaviour

The link between stresses and strains is governed by the properties of the material. If the material is rigid then strains are zero and movements can only occur if there is a mechanism. Otherwise materials may compress (or swell) or distort, as shown in Fig. 1.4. Figure 1.4(a) sho...