- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women Architects in the Modern Movement

About this book

Heroines of Space looks at four groundbreaking women architects: Eileen Gray, Lilly Reich, Margarethe Schütte-Lihotzky, and Charlotte Perriand. You'll see the parts they played in the history of modern architecture and get a clearer view of the recent past. The book explains the social and historical setting behind their coming into being and includes research on the factors around their roles as space makers to show you how they practiced architecture despite pressure not to. New in English, the Spanish edition won the 2006 Milka Blinakov Prize granted by the International Archive of Women in Architecture. Includes 150 black and white images and bibliographies for each architect.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women Architects in the Modern Movement by Carmen Espegel, Angela Giral in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPart I

Woman and Society

1

Woman and Architecture

Woman as the Subject of Architecture

The Masai hut is built by the woman, and she alone decides who enters it.

Norbert Schoenauer 1

It could be said that the house is woman’s archetypical architecture.2 Just as Gramsci affirms that there are no “philosophers” since we are all philosophers, we propose that there are no “women architects”, for all women connote architect and architecture as an endogenous element.3 In a basic anthropological construct the house has a uterine character and is manifested as a feminine symbol—related to the tomb, the lap, the womb, shelter—and has traditionally become the domain and territory of women.4

The snail makes the house he carries on his back, it is always at home, wherever it goes, but it is always alone, as woman. The shell is built from the inside, with its own saliva, and it is designed with a helicoidal geometry, the better to resist defensively. Whenever architects built their own houses, and more so if they are female, they aim not only to build a home but they are primordially building themselves up.5

A domestic structure is something extremely sophisticated, it reveals a particular way of living, of being, of thinking, and as such the architect is constructing his own thoughts as he designs his own home. From the careful selection of site to decisions about mechanisms of dwelling, the architect repeatedly demonstrates that he is building his super ego, as does anyone who builds a house for himself. Thus, paraphrasing Heidegger,6 building is the way we wish to be mortals on earth.

Another motivation for people to create architecture in general and their own dwelling in particular could be that genetic need for security, affection, approval and emotional support that Maslow7 demonstrated is in every human being.8

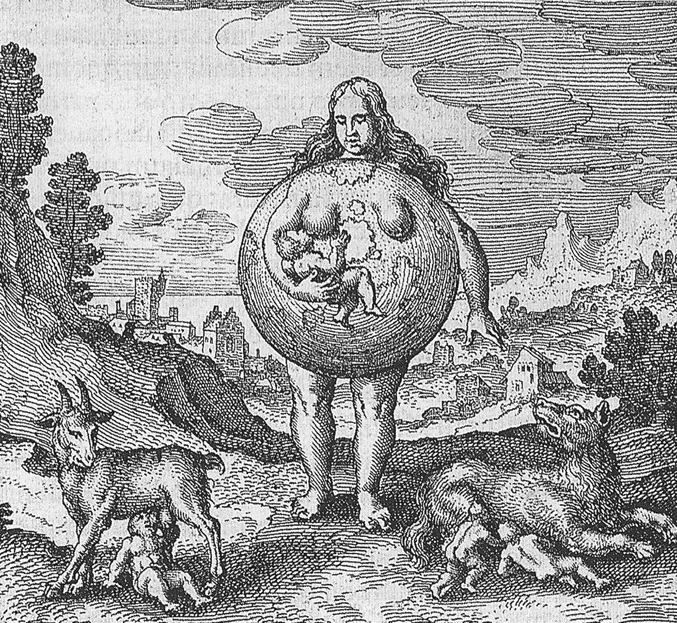

Figure 1.1 “Nursed by the Earth”, Fed by Mercury’s Water, M. Maier, Atalanta Fugiens, Oppenheim, Germany, 1617.

Wellcome Library, London.

Figure 1.2 “God as Architect”, the frontispiece of Bible Moralisée, Reims, France, Middle of XIII century.

© Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Vienna.

Women have traditionally been associated with the interior, with the detailed and the fragmentary. If we de-contextualize Paul Valéry’s statement that “there are no details in architecture,” we can take the terse ambiguity of this aphorism to mean that what is detailed denies architecture, or else that architecture, through its inherent need for integration, denies details. However the French writer establishes two different points of view for its comprehension. In the first place, he formulates an analogy to medicine and understands details as something that can obscure the center of the problem. In his second interpretation, detailing means to go from the general to the particular.

As an intermediate element between a global or structural vision on the one hand, and on the other, one that is specific and linked to details, furniture provides overall the dimensions and scale of interior space through its direct relation to the measurements of the human body.

We believe that the big evolves from the small because little things, details, require a greater time for observation, a temporal expansion of perception that magnifies their importance. In this sense, there are many psychologists who assert that women are better equipped for perceiving the whole with a greater degree of complexity of details. On the other hand, the perception of minute details produces in men a great feeling of troubling confusion.

For women, to have greater discriminating speed9 means that they have a greater appreciation of the totality, for they perceive all details with greater speed, while the abundance of details may generate in men an elevated bewilderment due to their perceiving a slower accumulation of them. That is to say, women can capture a greater complexity, even when it is unitary, while to men, especially as critics, the same object may seem complicated and excessively “designed.” It is also true that the more restricted is the field of vision the greater the need for visual stimulus, that is to say, for complexity.

Thus Le Corbusier’s motto of “rotund forms, graceful details” synthesizes this ambivalence between masculinity and femininity, between the generalist volu-metric outside and the particularistic detailed spatial inside.

The First Women Architects

The tent is always pitched by women. The first step entails the clearing of the site on level ground. Next the tent cover is spread on the ground. Then the ropes are pulled out and staked. Starting from one corner, poles are pushed up one by one. When the tent roof is aloft, the rear wall (ruag) as well as the dividing curtain (qata) are pinned in place. This whole operation is usually completed within an houre. […] The women’s side of the tent, often bigger in area than the man’s side, is the living and working area for the whole family: the man’s side, covered with carpets, is the reception area.

Norbert Schoenauer 10

The study of human habitat throughout the centuries has been a subject of the Rumanian architect and anthropologist Norbert Schoenauer, who has analyzed

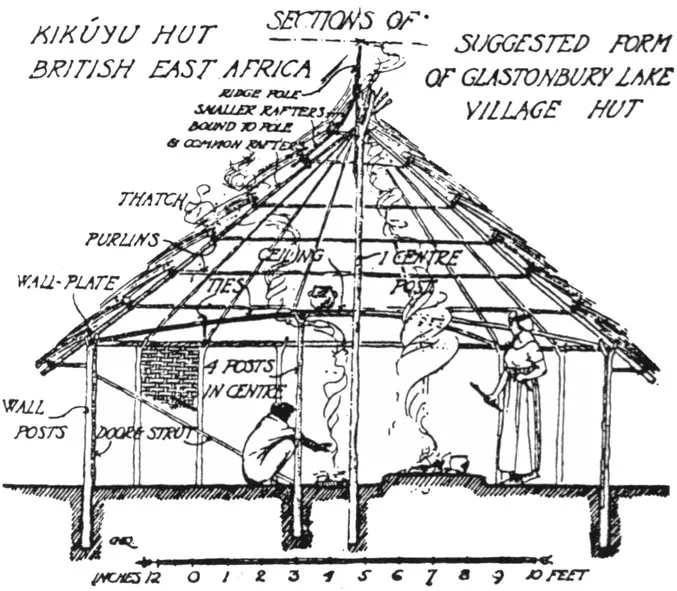

Figure 1.3 Comparative sections of an African hut and a primitive British cabin.

Luis Fernández-Galiano: El fuego y la memoria: Sobre energía y Arquitectura.

numerous examples of shelters built by women in different types of pre-urban settlements, in nomadic, semi-nomadic and sedentary societies throughout the world.

Three types of tribes are included in the first of these groups, that of ephemeral dwellings: the African bushmen, kung, who inhabit the arid zones of the Kalahari desert; the bambuti pygmies of the Ituri rainforest in Africa; and the Australian aboriginals called arunta. In the first two groups the construction of huts is a woman’s job, it resembles more a cumulative and quantitatively formal pattern of bird nests than a qualitatively architectural structure.

The kung bushmen have an independent nomadic life, based on collective hunting and gathering. Their groups are constituted by 25 to 30 persons. “Men hunt, make weapons and prepare the skins for their loin cloths; women gather food and wood, build the huts, kindle the fires, cook and keep the camp clean.”11

For the bambuti pygmies building the shelter is also women’s responsibility. They push young trees into the ground while squatting until firmly lodged. Once they have formed a circle of trees around them they all stand up and skillfully flex the tree trunks over their heads, twisting and crisscrossing the small branches until completing a structure. When the framework is completed they gather large heart-shaped leaves of the mongongo and split the bottoms of their stems in order to string together two or three, which are then hung over the framework as if they were slates, overlapping them in order to form a waterproof cover. Sometimes up to four women work together in the building of a single hut. Some hang the leaves on the outside; others push the leaves from the inside, tucking and securing them from top to bottom.

The second group, with dwellings that are intermittently temporary, includes the tents of the North American plain indians, who migrated following the buffalo through the prairie. These tribes used to construct a wooden structural skeleton over which they put buffalo skins sewn together. Setting up and dismantling these conical abodes was a woman’s job and it took approximately one hour. Tanning, cutting and sewing the leather wraparound was also entrusted to women, who frequently ornamented them with elaborately painted graphics.12

Another example of this type of dwelling that are transitory but with a greater capacity (community shelters) and bigger dimensions (30 meters long, 18 meters wide and 9 meters high approximately) are the malocas of the erigbaagsta indians that inhabit the North East basin of the Amazon river. Life is communal and everybody participates in the erection of the house and in working the land. Weapons are the only personal possessions.

The third group is that of periodic or temporarily regular dwellings, typical of the nomads whose cultural development stage is halfway between the primitive hunter-gatherers and agricultural societies. Among these we can count the kirghiz yurt (with a domed roof), and the mongol yurt (with a conical roof) for both of which the construction and dismantling is a woman’s job. The tent developed by the äir-tuareg who inhabit the arid plains of the Sakelian zone at the edge of the Sahara, does not take long for women to put up or take down. Finally, the black tents of the bedouin shepherds—bedouin means “men of the tent”—of Western Asia or Northern Africa are always put up by women.

The fourth group comprises the seasonal abodes, occupied for several months of the year. Outstanding among these is the female construction of the dwellings of the masai who inhabit the prairies of Kenya and Tanzania. The dwelling called boma is a kraal—fenced hamlet—in the shape of an arc with high thorny fences, whose construction requires about a week.

On the other hand, women are also strongly linked to movable goods. For instance the hopi, zuni, acoma and other indian tribes of the semi-desert plains of Arizona and New Mexico have a social organization based on a system of matrilineal, matrilocal clans and tribal society. The clan owns the gardens, arable lands and water springs. However, women own the furnishings of the dwelling and the stored harvest, while men own the cattle, tools, personal effects and religious ceremonial objects.13

Furnishings have thus been traditionally feminine. The bride’s trousseau usually contains furniture, kitchen tools and linens, especially when women are not allowed to inherit land or property. The belongings that the wife brings into the household indicate the nomadic character that women had in patrilineal societies, so she could only take along portable goods, but nothing permanent.

Examples could be multiplied almost indefinitely, thus we have shown here only those considered more important.

The House of the Mother Versus the House of the Father

When women are exchanged men are exchanging equal objects. But there is a difference between exchanging a woman and exchanging a hare. The woman brings with her a network of social and affective relationships with those with whom an alliance is desired, and she is capable of establishing equivalent relationships in her new environment. She is, thus, the transmitter and generator of social and affective relationships, linked to both allied groups, therefore has the capacity of bearing children to the re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- About the Author

- Preface

- Introduction

- PART I Woman and Society

- PART II Four Chronicles

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Index