![]()

1

Introduction

School design matters?

Credit: © Martine Hamilton Knight

The Design Matters? project investigated the relationships between design, practice and experience of secondary schools built in England in the early 2000s under the Building Schools for the Future (BSF) initiative and the Academies Programme (see facing page for an example). We studied a sample of these new-build schools within a decade of their inception, alongside comparator schools in the same locality. Our interest was in the ways in which design influenced the day-to-day experiences of school communities, with a particular emphasis on the transitions between different learning environments.

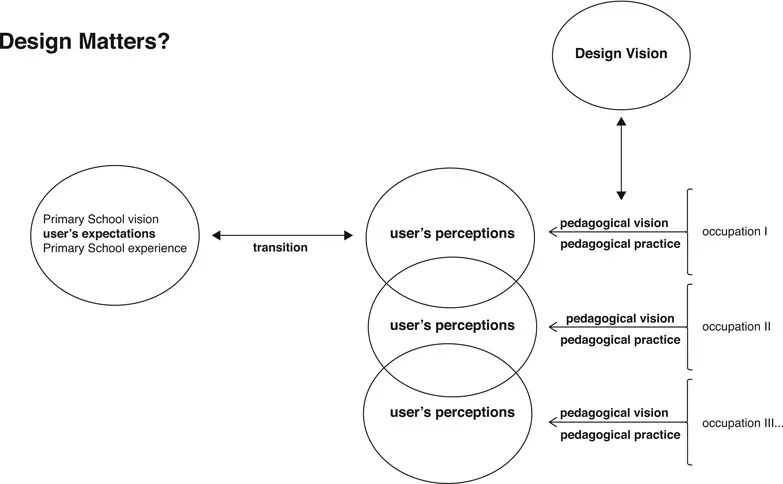

Design Matters? was a unique multi-disciplinary collaboration between schools, architects, engineers, educationalists and policymakers. The history and methodology of the project will be described more fully in Chapter 2. In brief, our aim was to extend beyond typical approaches to post-occupancy evaluation conducted on the performance of new buildings in order to gain insights into the effects of new designs on the lived experiences of members of school communities. We had a particular interest in the effects of design on pupils transferring from primary school as shown in Figure 1.1. We followed cohorts of students from Year 6 (ages 10–11), the final year of primary school in England, to the end of Year 8 (ages 12–13) through whatever changes in pedagogic approach and leadership took place. We developed a range of innovative, non-directive approaches to data capture, in order to arrive at the richest possible account through a range of first person (‘I/We’) and third person (‘She/He/They’) perspectives in these successive occupations.

The theoretical perspectives we brought to bear were inevitably influenced by the lead investigators’ previous work, particularly Daniels’ work on schools as cultural historical activity systems, and Stables’ work on education and semiotics.

A central issue in the Design Matters? project was that of the relationship between the school context and perceptions and actions of the individuals who study and teach within it. The field abounds with descriptors such as ‘sociocultural psychology’, ‘cultural historical activity theory’, each of which has been defined with great care. However, confusions persist alongside what still appear to be genuine differences of emphasis. As Wertsch et al. (1995: 11) argue, they all attempt to explicate the ‘relationships between human action, on the one hand, and the cultural, institutional, and historical situations in which this action occurs on the other’. Our challenge brought questions about the nature of context into focus. A key figure in the development of cultural historical activity theory is Michael Cole (1996) who distinguishes between two understandings of the word ‘context’. The first is roughly equivalent to the term

‘environment’ and refers to a set of circumstances, separate from the individual, with which the individual interacts and which are said to influence the individual in various ways (Cole, 2003). Use of this understanding can lead to studies of how a context, in our case a school design context, influences action within a school. In the second, understanding individual and context are seen as mutually constitutive. In the words of the Oxford English Dictionary, context is ‘the connected whole that gives coherence to its parts’, a definition which has strong affinities to the Latin term ‘contextere’, or to weave together. When used in this way, the ability to segment child and the context is problematic, but an analytic distinction that depends upon a large, perhaps unaccountably large, set of factors operating in bi-directionally over time in an active process of framing that can be unravelled in an instant (Cole, 2003). It is this second understanding of context which underpins the various approaches to the study of human activity that have been derived from the work of the Russian social theorist, L.S. Vygotsky. This notion of context is important in our work because it renders the tactic of parsing independent variables and identifying single factor effects (such as school design) problematic.

Figure 1.1 Overall schema of Design Matters?

In activity-oriented approaches, conceptual isolations between individual, objective world and activity are avoided. Vygotsky (1987) offers a dynamic and wide-ranging model that explains the process of inter-nalisation of semiotically mediated social forces. Even apparently the most individual and autonomous actions are situated in a context which must itself be viewed as an active participant in the structuring of their activities. This understanding of the active making of context in which design provided the tools for the active construction of school context was a key understanding at the inception of the project.

Stables has also long been interested in semiotic mediation in schooling, focusing on perspectives from the history of semiotics. From this he has, through a series of publications, attempted to develop a distinctive ‘edusemiotic’ perspective (e.g. Stables, 2016: Stables et al., 2018).

From this semiotic perspective, our surroundings do not determine how we respond to them. Consider how the agoraphobe or the claustrophobe would react to a small dark room or an open field. Each of us is predisposed to attach certain significances to certain aspects of the places in which we find ourselves. This is not merely a matter of psychological or emotional trauma, our assumptions about social class and individual identity are also important. Each of us is strongly impelled by considerations of what ‘people like us’ and ‘people like me’ do and where we belong. For example, this is witnessed in one school context in the statement of a young student who when interviewed about his newly built school stated that ‘this school is too posh for us’.

Living is semiotic engagement (Stables, 2006), a process of engaging with signs, each of which has a different significance for us. Signs operate in space and time, and when spaces are occupied and used at particular times they become places. We are always in places: places are the sites for the events that constitute our lives. The environment is a collection of significations not merely a mass of entities to which we are indifferent. Selection and values lie behind what we notice, find important, and like or dislike about where we are. This is not merely true of the human world: consider that the same blade of grass in a field may be a snack for a cow but a pathway for an ant. Semioticians refer to the environment of any organism as its umwelt. Each organism has its way of negotiating its environment: its innenwelt. Two other semiotic concepts that are relevant to a discussion of the role of school design are those of lebenswelt (the human cultural world: a term not exclusive to semiotics) and semiosphere, the totality of all significations (Lotman, 2005). On this account, a school is a particular umwelt located within a particular lebenswelt (by calling the place a school, we are giving it particular cultural meaning), to which all relevant actors – teacher, students, parents, ancillary staff, even visitors – react according to their particular innenwelt. In this sense, the innenwelt may be compared to Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of the habitus: the set of dispositions that collectively determine how we respond to a particular situation, or, in Bourdieu’s terms, locate ourselves within a particular ‘field’ (Bourdieu, 1993). The semiotic account only differs from Bourdieu’s in being less explicitly sociological, though it does not deny the value of sociological categories, and in taking a strongly organic view of the individual and their response to their environment, that renders a structural account as always less than complete. For example, social class might be understood as a powerful influence, but even studying the intersection of class with other structural factors such as gender, age or ethnicity falls short of a complete understanding of an individual’s life world.

Taken together, these sets of perspectives provided the analytical framework for Design Matters?

Overall, as the project progressed, we came to agree that one issue above all was predominating: that of the relationship of design to practice. This is both complex and at times difficult to understand, as we found some of our sample schools underwent several changes of occupation, and that different occupiers interacted with the design in different ways. What seems beyond doubt, however, is that design influences practice, but it does not simply determine or ‘cause’ it.

Design Matters? would not have been possible without the invaluable support of many schools, teachers and students and others in the architectural and educational professions, and of other academics with similar interests to ourselves. Above all, we wish to thank the AHRC for supporting the project with grant AH/J011924/1.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1993) The Field of Cultural Production. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Cole, M. (1996) Culture in Mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cole, M. (2003) Vygotsky and context. Where did the connection come from and what difference does it make? Paper prepared for the biennial conferences of the International Society for Theoretical Psychology, Istanbul, Turkey, 22–7 June.

Lotman, J. (2005; first published 1984 in Russian) On the semiosphere (trans. W. Clark), Sign Systems Studies, 33(1): 205–29.

Stables, A. (2006) Living and Learning as Semiotic Engagement. New York: Mellen.

Stables, A. (2016) Education as process semiotics: Towards a new model of semiotics for teaching and learning. Semiotica, 212: 45–58.

Stables, A., Nöth, W., Olteanu, A., Pesce, S. and Pikkarainen, E. (2018) Semiotic Theory of Learning: New Perspectives in Philosophy of Education. London: Routledge.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1987) The Collected Works of L.S. Vygotsky. Vol. 1: Problems of General Psychology, Including the Volume Thinking and Speech, ed. R.W. Rieber and A.S. Carton, trans. N. Minick. New York: Plenum Press.

Wertsch, J.V., del Rio, P. and Alvarez, A. (1995) Sociocultural studies: History, action and mediation, in J.V. Wertsch, P. del Rio and A. Alvarez (eds.), Sociocultural Studies of Mind. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–34.

![]()

2

School Design

What do we know?

The overall driver of the project was the question as to whether design matters. Does design make any difference to practice? The answer is not a simple yes or no, rather it calls for a consideration of the relationship between the two. In the, thankfully, distant past, psychology was preoccupied with the nature – nurture debate and pursued forms of analysis that assumed a linear additive relationship rather than seeking and developing more sophisticated accounts of the interrelationships between the two.

The relationship between design and practice has a similar history with suggestions that design alone can change behaviour locked in conflict with those that suggest that it has little or no impact. Neither argument has developed a sophisticated model of the relationship between the two. There has been recognition of the complex nature of the influences that are brought to bear on design and on the nature of the knowledge that is needed for design to ‘work’.

The struggles to agree upon what counts as design knowledge and its cultural identity can therefore be perceived as affecting and being affected by a complex system involving economy, production, social significance, consumption, use of objects, and so on.

(Carvalho and Dong, 2006, p. 484)

One of the major challenges of the Design Matters? project was to develop an understanding of the Design – Practice relationship. This required an in-depth engagement with the relevant literature and several cycles of analysis, portrayal and interrogation of the data. The contradictions and dilemmas that arose in this process became the driving force of our thinking and the development of the arguments that we present in this book.

The research examined school designs and the pedagogic practices that were witnessed in them. The project collected students’, teachers’ and parents’ perceptions of their school environment over two years after occupation of new designs from the Building Schools for the Future and the Academies Programme in England. The Building Schools for the Future initiative gave rise to designs that aimed to provide inspiring learning environments and exceptional community assets over an extended period. The intention was to ensure that ‘all young people are being taught in buildings that can enhance their learning and provide the...