- 589 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Laser Beam Shaping: Theory and Techniques addresses the theory and practice of every important technique for lossless beam shaping. Complete with experimental results as well as guidance on when beam shaping is practical and when each technique is appropriate, the Second Edition is updated to reflect significant developments in the field. This authoritative text:

- Features new chapters on axicon light ring generation systems, laser-beam-splitting (fan-out) gratings, vortex beams, and microlens diffusers

- Describes the latest advances in beam profile measurement technology and laser beam shaping using diffractive diffusers

- Contains new material on wavelength dependence, channel integrators, geometrical optics, and optical software

Laser Beam Shaping: Theory and Techniques, Second Edition not only provides a working understanding of the fundamentals, but also offers insight into the potential application of laser-beam-profile shaping in laser system design.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Laser Beam Shaping by Fred M. Dickey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

21 | Introduction |

Beam shaping is the process of redistributing the irradiance and phase of a beam of optical radiation. The beam shape is defined by the irradiance distribution. The phase of the shaped beam is a major factor in determining the propagation properties of the beam profile. For example, a reasonably large beam with a uniform phase front will maintain its shape over a considerable propagation distance. Beam shaping technology can be applied to both coherent and incoherent beams.

Arguably, there exists a preferred beam shape (irradiance profile) in any laser application. In industrial applications, the most frequently used profile is a uniform irradiance with steep sides, flat-top beam. This is due to the fact that the same interaction (physics) is accomplished over the illuminated area. Flat-top beams also have applications in laser printing. However, this is not the only profile of interest. Laser disk technology uses a focused beam with minimized side lobes to eliminate cross talk. Other patterns of interest in applications include shaped lines, rings, and array patterns. Some of the major applications of laser beam shaping are discussed in detail in Laser Beam Shaping Applications.1

Although the laser was invented in 1960, there were only about eight papers on laser beam shaping that appeared in the literature before 1980. A brief history and overview of laser beam shaping is given in the 2003 Optics & Photonics News paper “Laser Beam Shaping.”2 The rate of the appearance of laser beam shaping papers grew linearly, but slowly, until about 1995 when the rate increased dramatically. There is evidence that considerable research and development work on laser beam shaping was done in the period before 1995, but was not published for proprietary reasons. Starting in 2000 and continuing to the present, there have been 14 International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE) laser beam shaping conferences.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 The history of laser beam shaping is treated by Shealy in Chapter 9 of Laser Beam Shaping Applications.

A flat-top laser irradiance profile can be obtained by expanding the beam to obtain a pattern with the desired degree of uniformity. This approach intrudes very large losses in energy throughput. In almost all beam shaping applications, it is desirable to minimize the losses. The two major beam shaping techniques for producing a uniform beam are field mapping and beam integrators (homogenizers). These techniques can be designed to have very low losses.

Field mapping is the technique of using a phase element to map the laser beam into a uniform beam (or other profile) in a given plane. Field mappers are applicable to single-mode (spatially coherent) lasers. Producing vortex beams is also an example of field mapping. The individual lenslets in beam integrators function as field mappers.

Beam integrators break up the input beam into smaller beamlets that are directed to overlap in the output plane with the desired shape. They frequently consist of a lenslet array and a primary lens. Beam integrators can also be implemented using a reflective tube and focusing the laser beam on the input aperture of the tube. This approach is called a channel integrator. Beam integrators are especially applicable to low spatial coherence beams. The low spatial coherence of the input beam reduces the speckle pattern that is inherent in the output of beam integrators. There cases when it is useful to apply beam integrators to spatially coherent beams when the speckle can be tolerated. It is interesting to note that optical configurations that can be considered beam integrators were introduced long before the advent of the laser.17,18

The ability to do beam shaping is limited by uncertainty principle of quantum mechanics, or equivalently the time–bandwidth product inequality associated with signal processing. Mathematically, the uncertainty principle is a constraint on the lower limit of the product of the root-mean-square width of a function and its root-mean-square bandwidth. It can be directly applied to the beam shaping problem because of the Fourier transform relation in the Fresnel integral used to describe the beam shaping problem. In fact, the uncertainty principle is generally applicable to diffraction theory. Applying the uncertainty principle to the general diffraction problem associated with laser beam shaping, one obtains a parameter β of the form

(1.1) |

where:

r0 is the input beam half-width

y0 is the output beam half-width

C is a constant that depends on the exact definition of beam widths

z is the distance to the output plane

The parameter β is also obtained when applying the method of stationary phase to diffraction problems.

The value of β must be sufficiently large for successful beam shaping to be accomplished. It should be noted that the system designer has some design control over β by specifying r0 or, possibly, the other three parameters in Equation 1.1. Because of its fundamental nature, β is applicable to field mappers and beam integrators.

It is commonly stated that when β is large the problem can be treated using geometrical optics. This is true for field mapping systems designed to produce flat-top profiles. However, techniques such as diffractive diffusers inherently require the use of diffraction theory in the design process. In addition, diffraction theory is useful in determining some general properties of beam shapers. An example is the wavelength independence of some field mapping configurations (see Chapter 5).

In no case can quality beam shaping be accomplished if β is small. It is suggested that this parameter be considered in the initial stage of any beam shaping system design.

As stated earlier and clearly defined in the subsequent chapters, the theory, calculations, and strategies for designing laser beam shaping systems have come a long way. Although success in the application of beam shaping does not only come from knowing how to calculate a design and understanding the guiding parameters such as β, it simply provides a working baseline of knowledge.

When an engineer or a development team considers the integration of optics into a process, they need to take into account a number of primary as well as ancillary variables that start at the process and work backward through the optical system to the laser source itself. Failure is inevitable if beam shaping is considered simply as an off-the-shelf product that is easy to integrate. Consideration of a new beam shaper design or the purchase of an off-the-shelf beam shaping product must be approached carefully since the beam shaper’s performance is dependent on the stability of the laser source itself. Offering a considerable number of challenges due to the dynamic nature of laser processes simple changes to duty cycle often result in pointing instability, divergence shifts, beam intensity distribution, and power fluctuations, to name a few. All of the variables identified need to be scrutinized and prioritized so that the beam shaper can be designed and configured with an appropriate set of preconditioning optics or enough axes of adjustment to provide fine-tuning if required.19 These items are only part of what it takes to be successful; a willingness to tackle the hardest problems first is the only true guarantee.

Since the introduction of lasers into the industrial marketplace, those of us involved in its application have been in a technology race, whether we like it or not. Driving innovation is the key to success for technologists, but that innovation in many cases is found by simply searching for insight from existing successes within the scientific community or other markets where similar technology is applied. That insight can take many forms such as exposure to existing and past technologies or merely taking calculated risks by blazing a new trail by pulling together various technologies and integrating them into a new solution. Whether applying old or new ideas, innovation of beam shaping technology requires identifying the parameters within the context of a laser process that matter and moving through them systematically to deliver an elegant solution.

Below are two examples that highlight the development of “diffractive and refractive” laser beam shaping technology over the past 20 years and hit upon this theme. From a historical perspective, the examples were selected to illustrate the progression and impact of laser beam shaping on the industrial laser system marketplace. No attempt has been made to select specific technological milestones of equal importance nor should the reader consider these items critical in terms of a grand historical record. These examples are simply moments in time where insight gained by early adopters led to experimentation and the evolution of laser beam shaping within the industrial laser and laser materials processing field. Let us explore a few exemplar beam shaper solutions that were brought to market, which is the point where true innovation ends, as well as demonstrated.

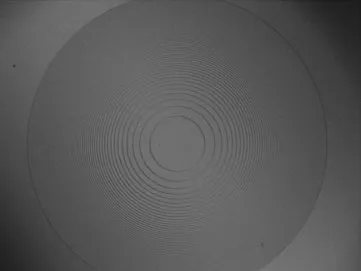

As mentioned earlier, field mappers are phase elements that redistribute laser light to form a new desired irradiance and phase profile. These phase elements commonly take two highly efficient forms, either traditional refractive phase elements, such as custom aspheric lenses (>96% efficient), or diffractive elements, such as diffractive lenses (>85% efficient), where the phase coefficients are compressed into 2Π surface reliefs. Figure 1.1 shows a Gaussian to round flat-top diffractive field mapping beam shaper element. In many cases, these diffractive optics are based upon an aspheric phase design. It should be stated that fabrication plays a major role in the efficiency of such field mappers and during the early 1990s the costs for fabricating these elements were significant; 20 years later, these elements are now manufactured at scale with competitive pricing that has made them available for lower cost laser marking applications.

FIGURE 1.1 Gaussian to round flat-top diffractive field mapping beam shaper element.

Although numerous far- and near-infrared (FIR/NIR) lasers such as CO2 and Nd:YAG have benefited from more traditional beam shaping and field mapping aspheric systems, frequency tripled and quadrupled diode-pumped solid-state (UV DPSS) lasers (355 and 266 nm, respectively) have benefited from field mappers to a greater degree. As UV DPSS lasers began to be adopted into larger volume laser system markets, it quickly became...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Editor

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Mathematical and Physical Theory of Lossless Beam Shaping

- Chapter 3 Laser Beam Splitting Gratings

- Chapter 4 Vortex Beam Shaping

- Chapter 5 Gaussian Beam Shaping: Diffraction Theory and Design

- Chapter 6 Geometrical Methods

- Chapter 7 Optimization-Based Designs

- Chapter 8 Beam Shaping with Diffractive Diffusers

- Chapter 9 Engineered Microlens Diffusers

- Chapter 10 Multi-Aperture Beam Integration Systems

- Chapter 11 Axicon Ring Generation Systems

- Chapter 12 Current Technology of Beam Profile Measurement

- Chapter 13 Classical (Nonlaser) Methods

- Index