![]()

Part 1

Why a text on positive psychology in sport and physical activity?

![]()

1

Introducing positive psychology and its value for sport and physical activity

Abbe Brady and Bridget Grenville-Cleave

A brief history of positive psychology

Positive psychology (PP) originates from the University of Pennsylvania, USA. It was founded in the late 1990s by psychology professors Martin Seligman, whose academic interests shifted from learned helplessness to learned optimism, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a world expert in creativity and flow. One of the main reasons often stated for the creation of this new branch of psychology is the view that traditional psychology had focused too heavily on pathology – in other words, understanding human problems such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. It was argued that traditional psychology devoted very little attention to the study of wellness and the ‘positive’ aspects of life, such as resilience, character strengths and well-being, with the same academic rigour. As an example, consider the psychology of coach-athlete relationships. A conventional social psychology approach may focus on aspects of power (use and abuse), communication preferences, conflict management, commitment and compatibility. Applying a PP lens we might instead look at the contribution that each individual’s character strengths make to the relationship, the effect of over- and underplayed strengths, harmony, inspiration, creativity, co-operation, celebration, passion, trust, honesty, forgiveness, shared meaning and the role of playfulness and humor in these relationships.

This imbalance between negative and positive foci in psychology has been illustrated by comparing the total number of academic papers published about ‘negative’ psychology topics with the total number published about ‘positive’ psychology topics. During the three decades spanning 1972 – 2006, in the PsycARTICLES database more than 113,000 articles were published about depression. In the same period, fewer than 23,000 were published about well-being and fewer than 1,600 about subjective well-being. Even if we accept the argument that disease merits greater professional attention than wellness, it is clear that an opportunity exists to increase our scientific understanding of wellness.

Since 1998 many researchers and practitioners have been inspired to work in this field, writing research articles and books on the subject, publishing new academic journals dedicated to the science of happiness and establishing several professional associations. Across the world, universities have introduced PP undergraduate modules and postgraduate degrees starting with the University of Pennsylvania MAPP, the MSc in Applied Positive Psychology at the University of East London and the Graduate Certificate in Applied Positive Psychology at the University of Sydney.

PP is not just making its mark in academia, however. Following the pioneering example set by the Kingdom of Bhutan in the 1970s, the national and local governments of many countries have concluded that conventional objective and largely economic measures such as gross domestic product are insufficient on their own to measure society’s progress. As a result, they are adopting the view that PP considerations, particularly the emphasis on subjective well-being and how people think and feel about their lives, can help create more meaningful and effective public policy.

The landscape of positive psychology

Although the PP movement is well into its second decade, it would be fair to say that there is no unifying theory. Many scholars seem content to accept relatively loose definitions of PP, for example, “the scientific study of what goes right in life, from birth to death and at all the stops in between” (Peterson, 2006, p. 4), “the scientific study of ordinary human strengths and virtues” (Sheldon & King, 2001, p. 216) and “(the) science of positive subjective experience, positive individual traits, and positive institutions” (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p. 5). Importantly, these scholars do not claim to have invented happiness and well-being, nor to be the first to study them. Numerous different definitions and theories of well-being, happiness and flourishing exist, some of which are discussed in Chapter 2.

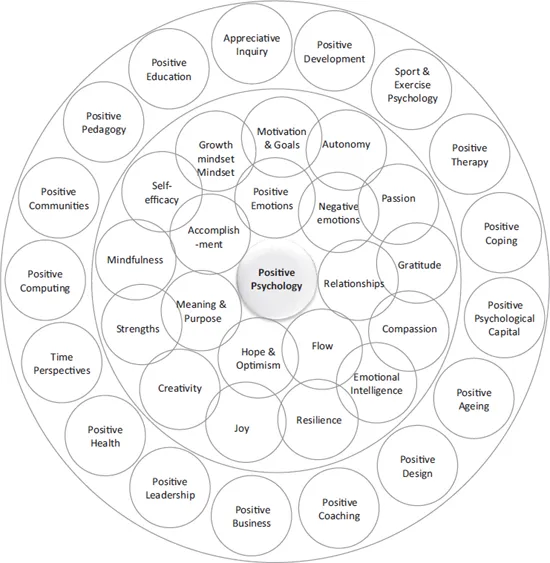

PP incorporates a multitude of topics, some of which are undoubtedly new to scientific study (e.g. forgiveness and awe) and others which are not (e.g. motivation and emotional intelligence). PP is probably most usefully described as an ‘umbrella’ term which brings together into one collective body many individual, sometimes isolated, sometimes novel and often familiar, strands of research and theory related to well-being. Notwithstanding the recent emergence of ‘Second Wave Positive Psychology’ or ‘Positive Psychology 2.0’ which we discuss further in this chapter, there is every reason to believe that PP will continue to exist as a separate field of scientific inquiry until such time as conventional psychology naturally gives as much attention to the study of what is good in life as it does to what is problematic.

Park and Peterson (2003) suggest that positive institutions facilitate the development of positive traits at the individual level, which, in turn, lead to positive subjective experiences and states. In contrast to this top-down view of human happiness, Barbara Fredrickson, whose major contribution to PP has been the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (2001), suggests that a bottom-up approach is equally valid. She argues that our everyday subjective experience of positive emotions leads to a broadening of our natural ways of thinking and behaving, as well as to the development of additional personal resources, such as problem-solving ability and creativity, over time. In other words, our long-term happiness and ability to flourish and succeed are built on our short-term positive subjective experience. These contrasting approaches demonstrate how far PP still has to travel before we reach a common shared understanding of human flourishing – what it is, its origins and its outcomes.

To illustrate the wealth of topics commonly included under the positive psychology umbrella, the mindmap of PP topics and applications in Figure 1.1 provides a useful starting point.

To illustrate the scope of PP it can be helpful initially to consider two contrasting views of human happiness, hedonia and eudaimonia, which have their roots in Greek philosophy. Simply put, hedonic well-being concerns the form of happiness experienced from feeling pleasure in the moment. Eudaimonic well-being is a broad term often used to refer to the happiness gained from having meaning and purpose in our lives, doing things which facilitate personal growth and enable us to fulfill our potential, and feeling that we are in some way connected to the wider world or have a higher calling.

Figure 1.1 An illustration of positive psychology topics and applications

Some scholars have proposed other forms of well-being, including ‘prudential’ happiness (Haybron, 2000), ‘chaironic’ happiness (Wong, 2009) and ‘halcyonic’ happiness (Gruman & Bors, 2012), which are worthy of separate consideration. Do people the world over experience happiness in the same way or is it culture-specific (Lo & Gilmour, 2004)? What is the role of socio-economic factors in well-being (however defined)? Does PP only apply to residents of countries which are ‘WEIRD’ (western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic), and so on.

Contemporary issues in positive psychology

Since its inception, the exponential growth of PP has produced a vast new landscape of enquiry. Understandably, the field has attracted some criticism. What is presented next are some of the more important criticisms, which are useful for both students and practitioners to consider.

1. It’s nothing more than positive thinking

One of the major criticisms consistently levelled at PP is that it takes a ‘Pollyanna’ approach to life, promoting the Norman Vincent Peale (1953) notion that if you think positively everything will be all right. In doing so, some critics argue that PP ignores or negates the value of commonplace ‘negative’ emotions such as anger, sadness and fear. Of course, what this particular interpretation also suggests is that mainstream psychology is negative and that PP is somehow a replacement for it. Seligman (2003), however, has made clear that PP is not a substitute for conventional psychology, rather it is a supplement to it.

Seligman has also distanced PP from Peale’s positive thinking approach by emphasising the fact that the latter is an armchair activity whereas the former is a science, based on a programme of rigorous empirical research. Whilst it is the case that some motivational speakers and trainers have become extremely successful by promoting the power of positive thinking, we cannot ignore the fact that the evidence base underpinning cognitive behavioral therapy, for example, does show that our ways of thinking about the world, how we feel and how we behave are interconnected (Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer, & Fang, 2012). However, to state that PP is positive thinking is incorrect.

Despite the advantages associated with optimism and positive construal, there are times when positive thinking could lead to disaster and problem-focused thinking is in fact preferable. Thinking that you can wing your final exams, that the red brake warning light on your dashboard is simply faulty, or that despite your lack of exercise over the last year you can begin a new fitness regime with a 10k run, are clearly not helpful uses of positive thinking, and may actually lead to difficulty, failure or worse. Seligman himself is keen to ensure that practitioners foster realistic optimism rather than blind optimism or optimism at any cost, which could do more harm than good. Positive psychology also acknowledges the importance that defensive pessimism and negative thinking play in high performance and well-being (Norem & Cantor, 1986; Norem & Chang, 2002). However, not content with these rebuttals and defences, some PP researchers have launched what is now referred to as ‘Second Wave Positive Psychology’ or ‘PP 2.0’, in which they also lambaste their ‘first wave’ colleagues with similar criticisms and present a ‘new’ phase of positive psychology study and practice to counteract them. This may seem somewhat unnecessary to those researchers and practitioners who have always taken a more holistic and nuanced approach; however, if it finally lays the ghosts of positive thinking to rest, perhaps that is a good thing. In conclusion we hope that even a brief glance at the mindmap in Figure 1.1 convinces readers that PP has a much broader and deeper reach than positive thinking.

2. Problems with definition, description and prescription

A second major criticism concerns the discomfort that many scholars feel at defining what is meant by ‘positive’ (and ‘negative’) and the suggestion that PP prescribes what you should (and shouldn’t) do to be happy and live a good life (Held, 2002). Even basic ...