eBook - ePub

Designing Technology Training for Older Adults in Continuing Care Retirement Communities

- 191 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Designing Technology Training for Older Adults in Continuing Care Retirement Communities

About this book

This book provides the latest research and design-based recommendations for how to design and implement a technology training program for older adults in Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs). The approach in the book concentrates on providing useful best practices for CCRC owners, CEOs, activity directors, as well as practitioners and system designers working with older adults to enhance their quality of life. Educators studying older adults will also find this book useful Although the guidelines are couched in the context of CCRCs, the book will have broader-based implications for training older adults on how to use computers, tablets, and other technologies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Designing Technology Training for Older Adults in Continuing Care Retirement Communities by Shelia R. Cotten,Elizabeth A. Yost,Ronald W. Berkowsky,Vicki Winstead,William A. Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Human-Computer Interaction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter one

Introduction and purpose

1.1 Importance of technology use for older adults in continuing care retirement communities

Ms. W. is an 87-year-old woman who lives in an assisted living community in Alabama. She has never been married, has no children, and only has one friend who lives several states away who she gets to see with any regularity. Other residents report that she rarely participates in group activities. She uses a wheelchair to transport herself. When we met Ms. W., she seemed lonely and somewhat depressed. She enrolled in our computer training program at the encouragement of the activities director. Over the course of training, Ms. W. became more outgoing and began to interact in other activities throughout the community. She also had a lot of fun—at one point, she mentioned that she had “gotten her hair done” twice a week for all her life, never missing an appointment, but during the training program she had forgotten about a hair appointment because she was so excited for “computer class!” At the end of the training program, Ms. W. said, “I’m a hot 87-year-old computer expert. I know how to Google!” She had even reconnected with a high school friend via email. Although not all older adults who learn to use computers and the Internet will respond like Ms. W., our research shows that older adults in continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs) can overcome the digital divide, reconnect with family and friends, and gain skills to enhance their quality of life.

We decided to write this book as we have seen the benefits for the quality of life that learning to use computers and the Internet can bestow on older adults in different types of care communities. There are no books available that focus on training older adults in CCRCs to use various types of technology. Although some older adults may find general technology use books beneficial as they try to learn to use computers or other technologies, such resources are frequently not sufficient; older adults often need tailored instruction and materials that cannot be found in “off the shelf” books. Older adults who move into these communities have special needs that necessitate different recruitment and training than what older adults in the general community require. The training methods provided in this book should be applicable to the general community of older adults too; however, the converse of this would not be true for the majority of CCRC residents.

There will be a rapid increase in the number of older adults in the next few decades (as detailed in the next section), accompanied by rapid changes in information and communication technologies (ICTs), and unprecedented growth in the number of independent and assisted living communities nationwide. Therefore, it is important to consider why older adults may want to use ICTs and how they could benefit from them as well as the best ways to help activity directors, caregivers, providers, and older adults keep up with changing technology. This information should make it easier for owners and administrators of CCRCs to decide whether they should offer training to their residents or whether using an outside organization to assist with this process would be more beneficial. Regardless of the approach taken, the material in this book serves as a best-practice guide for thinking about technology training for older adults in CCRCs. Given the increasing portion of the population moving into older demographic age groups, utilizing proven methods for keeping older adults connected and engaged will be critical for CCRC administrators and others who work with the growing population of older adults. The methods that we describe will likely be useful for teaching future cohorts of older adults to use novel technologies that perhaps are not available or have not even been created at this time.

The remainder of this chapter provides a comprehensive view of aging demographics, technology use among older adults, and the benefits of technology use in an aging population. Also detailed are the key audiences targeted in this book and what each can learn from this material.

1.2 Aging population demographics

1.2.1 Global trends

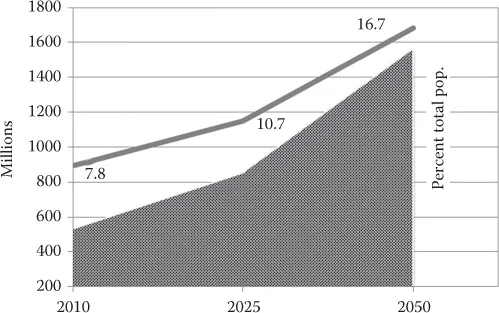

The aging population continues to grow globally. Estimates project that the global proportion of individuals over the age of 65 will double from 7.8% (524 million individuals) in 2010 to approximately 16.7% (1.5 billion individuals) in 2050. Figure 1.1 details the changes in percent population and population size of the worldwide older adult population from 2010 to 2050.

Growth of the older adult population is expected to continue as healthcare and technology continue to improve health outcomes and fertility rates continue to decline. This doubling of the proportion of the population over the age of 65 has profound implications for economic and social policy. Although the change in the aging population is occurring globally, rates differ greatly between developing and developed countries.

Developed countries—ones that have undergone demographic transitions and industrialization—have long been thought to be unduly burdened by this population shift. As individuals in these countries are living longer and children are considered more of an expense, fertility rates have dropped below replacement rates of 2.1 children per woman. This leads to a reduced workforce as older adults age out of the workforce and fewer children are born to replace them.

Figure 1.1 World population and the percentage of the total population aged 65 and older. Not only is the world population growing, but the percentage of older adults is also expected to grow. By 2050, 16.7% of the total population will be over the age of 65.

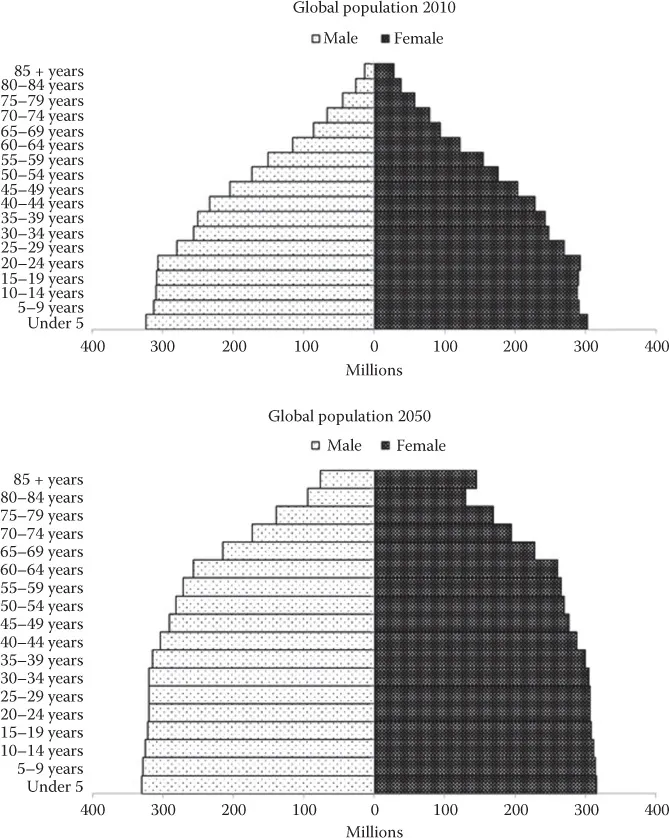

Countries throughout Europe and Asia are facing significant issues in workforce decline and shifting population pyramid structures. Other developed countries, such as the United States, Canada, and Australia, are experiencing slow growth in their workforce while still experiencing a growing population of people over the age of 65 who are often dependent on government welfare programs funded by taxes on working-age individuals. Population pyramids (Figure 1.2) detail the projected changing structure of the global population from 2010 to 2050.

With a reduced workforce and overall change in the number of aging individuals, some developed countries are confronting issues of increased numbers of individuals on social welfare programs in older age, and the need for greater resources for long-term care. As most developed countries are at or below the replacement rate—the number of children born per woman to keep the population rate stable—the overall population of many industrialized nations is declining. With fewer children being born and the population continuing to age, the issues of long-term care and social welfare programs will only become more significant as the next phase of demographic transition occurs.

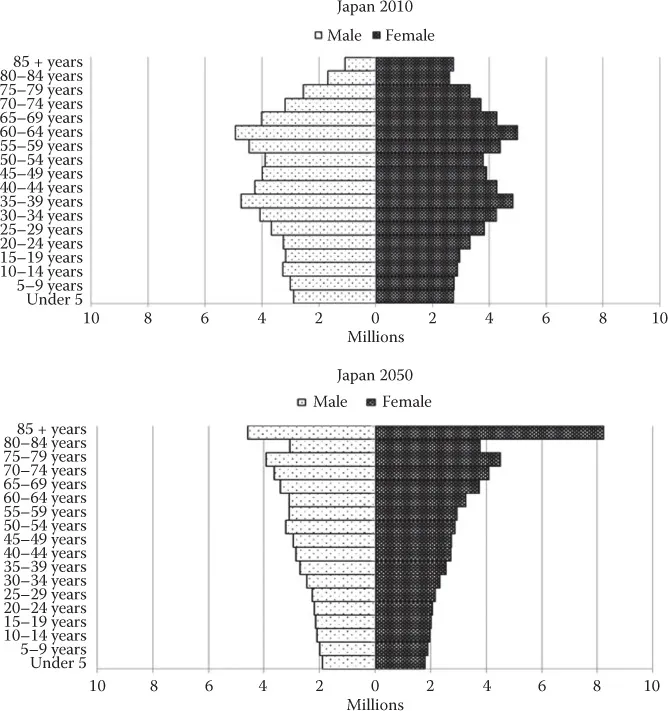

Not only are the overall populations of these countries continuing to age, but the numbers of oldest old are continuing to increase as well. The oldest old—those 85 years of age and older—are often the portion of the older adult population that is most burdened by chronic disease. Although the numbers differ greatly between countries, the oldest old as a total portion of the global population is expected to increase 151% between 2005 and 2030. Japan will be most impacted by this aging segment of the population. By 2050, 40% of Japan’s population will be 65 or older, and Japan will have the greatest percentage of oldest old in the world. Figure 1.3 shows the projected growth and distribution by sex of Japan’s older adult population from 2010 to 2050. The total portion of the oldest old will not increase quite as rapidly for the United States and some other newer developed countries.

Figure 1.2 Global population pyramid for 2010 and 2050. By 2050 the shape of the global population pyramid is expected to shift from a traditional pyramid structure to a more column-like structure as the population grows older.

Figure 1.3 Population pyramid for Japan for 2010 and 2050. By 2050 Japan’s population pyramid is expected to flip, with a majority of the population being over the age of 65.

Overall, developed countries are experiencing a significant demographic transition as the aging population continues to grow. Economic and social policies are being designed and implemented to address the changing population in developed countries, although they are not the only countries experiencing changes in their aging populations. Developing countries also have aging populations for which they are not structurally equipped. With increases in healthcare, individuals are living longer. In addition, many developing countries have experienced an epidemiological shift and are now dealing with chronic health issues more than acute health issues. As individuals are living longer, many developing countries are seeing a dramatic increase in life expectancy. Because of advances in healthcare, many developing countries are beginning to see increasing life expectancies and will soon be facing similar issues.

China is a unique and extreme example of aging in a developing country. Although China has made significant growth in the last three decades, it remains a developing country by the World Bank standards, as its per capita income is only a fraction of that of developed countries. The population of China is changing. Since the implementation of the one-child policy in China in 1979, the growth of China’s population has been stunted. In 2000, 10.1% of China’s population was over the age of 65. By 2050, it is projected to be 24% of the population, thus exceeding the global average.

1.2.2 U.S. trends

As the global population ages, the United States is also experiencing a graying of its adult population. This corresponds to the aging of the baby boomer population. Although the United States remains one of the youngest developed countries, compared to other developed countries, it has the greatest number of adults aged 65 and over and the greatest number of adults aged 85 and over. Among developed nations, the United States is second youngest to Russia in terms of median population age. Globally, the United States has the third-largest older adult population, with China having the first and India having the second.

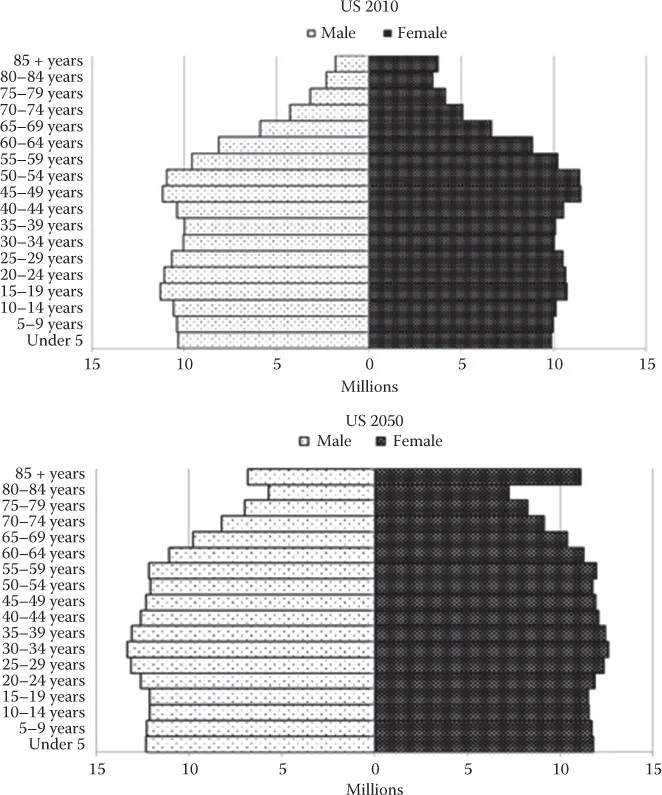

The impact the aging baby boomers will have on U.S. demographics is significant. Baby boomers are individuals born between World War II and the mid-1960s. This “boom” represented a significant spike in fertility rates in the United States. As the first baby boomer turned 65 in 2011, this spike in the population is now resulting in a significant demographic shift in the United States. Figure 1.4 shows how the aging of the baby boomer generation will impact the structure of the population pyramids from 2010 to 2050. Because the United States is still a relatively young developed country, the demographics of the country including, but not limited to, the older adult population will continue to change. The median age, dependency ratios, sex, and race of the older adult population is expected to experience significant transition as the baby boomers continue to age. These changes impact the number of workers in an economy, the number of individuals able to participate in active military service, and the amount paid into and withdrawn from federal aging programs.

Figure 1.4 Population pyramid for the United States for 2010 and 2050. The shape of the population pyramid in the United States is set to change dramatically as the population ages. The pyramid shows the dramatic increase in adults 65 years of age and older in the United States by 2050.

Although the United States experiences significant population growth from immigrants, the racial and ethnic composition of the older adult population should not be greatly impacted in the short term. As immigrants tend to be under 40 years of age, most will not be counted in the older adult population for at least another 25 years. However, by 2050, these demographics have the potential to shift dramatically, with almost 40% of the older adults in the United States reporting a minority racial status. Although the racial composition will vary between older adults and the oldest old, projections based on the 2010 Census suggest that the majority racial category among all older adults in 2050 will remain “white.” However, all categories of racial minority groups are expected to increase, with the largest change being seen in Hispanic oldest old (85 years of age and older) populations.

Sex ratio is another characteristic expected to see dramatic changes in the immediate future. In 2012, there were 77.3 men for every 100 women over the age of 65. Over the age of 90, there were 40.3 men for every 100 women. By 2050, it is projected that there will be 81.5 men for every 100 women over the age of 65 and 52.7 men per 100 women over 90 years of age. Although women continue to have a longer life expectancy than their male counterparts, the gap is narrowing. Men are beginning to live longer, with the greatest change being in the sex ratios of the ol...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Authors

- Chapter 1 Introduction and purpose

- Chapter 2 Continuing care retirement communities and the need for technology training

- Chapter 3 A prototype study

- Chapter 4 Complexities of and best practices for implementing technology training in continuing care retirement communities

- Chapter 5 Value of technology training

- Chapter 6 Recruiting and retaining older adults in technology training programs

- Chapter 7 Training decisions

- Chapter 8 Current needs for technological access and use in continuing care retirement communities

- Chapter 9 The future of technology use among older adults in continuing care retirement communities

- Chapter 10 Conclusions and final thoughts

- Bibliography

- Appendix

- Index