![]()

1 The Nature of General Practice

THIS chapter aims to explore the philosophy of general practice. What are its objectives? What is the nature of the problems that it faces and what solutions does it offer? These questions are important ones for the practice manager to address because she will have to subscribe to that philosophy if she is to make the most of her contribution to patient care.

Everyone who considers himself or herself to be ill needs a point of first contact with a physician which allows entry into the health care system. This frontline medical care is known as ‘primary care’ in contrast to that of ‘secondary care’ which is specialized and more sophisticated than that handled in primary care and to which access is usually gained only after being filtered or sorted within primary care. Most countries have some such system but whereas in the UK it is called ‘general practice’ in other countries it may be ‘family practice’, ‘primary medical care’ or ‘primary health care’. Whatever the title it has certain characteristics above and beyond being a point of first contact.

1 The problem presented is undifferentiated. People do not have to make decisions about the nature of their problem, only that they have one and that it is probably concerned with their health. They do not have to decide whether their chest pain is due to their heart, in which case they would need the advice of a cardiologist or that it may be indigestion and a stomach specialist would be more appropriate. Their problems may be life-threatening or they may be trivial. Furthermore it is the patient’s perception of this which is relevant, not the receptionist’s, the manager’s or the doctor’s, so access to care has to be as unrestricted as possible. This is a very important idea to grasp because it clearly shapes how we behave to patients, what we say and the sort of systems that we organize. General practice has to be ‘comprehensive’.

2 Care is offered to the family group. The fact that problems are undifferentiated and that any age may attend obviously allows all members of the family to be seen but the concept embraced is wider than this. All illness should be regarded as potentially ‘family illness’. It is clear that, say, marital disharmony will affect the husband and wife and almost certainly have an impact on children, grandparents and even brothers and sisters whose affections can be stressed. It is not so obvious that, say, a duodenal ulcer can affect the family but the diet, the need for rest and quiet, the effect upon temper, holidays, sexual relationships can all be factors in the management. Another perspective of the significance of family care is the need to explore and make the best of this opportunity within a consultation. The spouse who accompanies the patient is expressing concern and caring and needs to be considered. The act of immunizing a child is more than giving an injection, it is an opportunity to establish a relationship with a mother, to discuss feeding, growth, education and behaviour at a time when the mother is very receptive to these ideas.

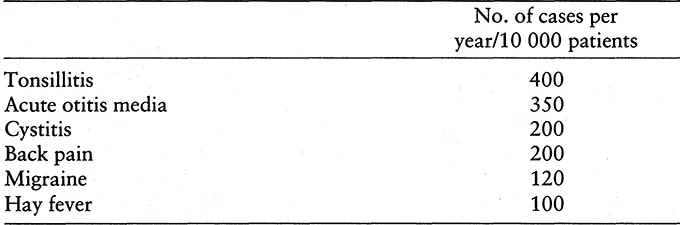

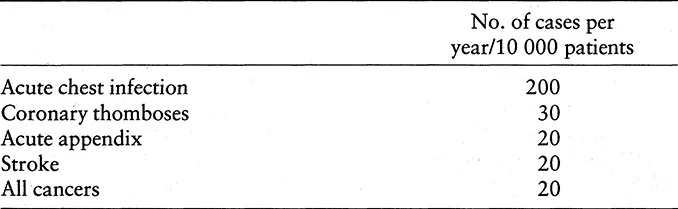

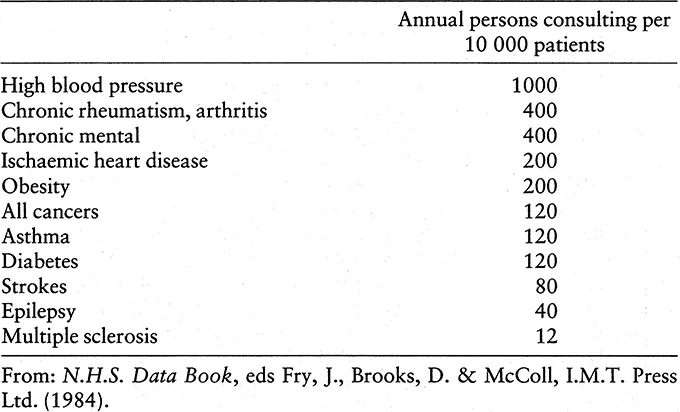

3 Care is continuous. Much care is episodic. A patient may come once with a boil, take advice, perhaps receive a prescription and have urine tested for glycosuria and then leave, but most care is prolonged for most illness is chronic or recurrent. Tables 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 show the approximate frequency with which common and rare problems may be seen in a practice of 10 000 persons and it will be noted that chronic disease is a longer list and represents several consultations for that condition each year. The right-hand figure gives the number of persons consulting per year from a list of 10 000 patients.

Nearly all chronic disease is now treated within the community. Some, such as hypertension, are nearly always treated within general practice, but other problems may sometimes be treated by other agencies, specialists, hospitals, private sources and so on. However, because primary care is continuous the record card is the only repository of all medical information and the responsibility for manipulating and co-ordinating care across boundaries, in short ‘managing’, is the task of general practice. That is why we have a referral system and why all the letters eventually return from the periphery to the centre of the web. The patient with a stroke may be seen at the hospital, or even admitted for a while, but the responsibility for continuity of care, for organizing transport, meals-on-wheels, physiotherapy or chiropody is ultimately that of general practice although, of course, it is often convenient to delegate it to others. Again the implications of this concept are great and the practice team has a vital role in co-ordinating good quality care. Certainly patients see this as a most important function and its breakdown as a fearful addition to existing problems of ill health.

Table 1.1 Minor conditions.

Table 1.2 Acute major conditions.

Table 1.3 Some chronic disease in general practice: annual person consulting rates.

It also has very important implications for management in terms of activity. Letters arrive from hospitals asking us to prescribe a drug, arrange an investigation or review after a period of time and that action has to be taken otherwise the patient may suffer, the hospital be given extra work or even litigation ensue.

Continuity of care has one other aspect that must be considered here. Care given by a variety of people can soon become fragmented and confusing for the patient. It needs some skill directed to the problem to enable one person, or as few people as necessary to become involved. For example a patient dying at home needs to be cared for by their nurse and their doctor. At the same time cover by other informed people is necessary when the key people cannot be there.

4 Care includes disease prevention and health promotion. One of the most profound shifts in the philosophy of general practice in the past few years has been the change from a ‘reactive’ pattern of working to a ‘pro-active’ one. The best simile is that provided by the fire brigade. Their ‘reactive’ pattern of work is to sally forth at high speed in response to a call that your house is on fire. Their ‘pro-active’ work involves calling to advise on safety precautions, fire-proof doors, smoke detectors, etc. that might prevent a catastrophe. Similarly, in general practice, when a family registers with the practice they are saying ‘please be there when we want you’ but they are also saying ‘please stop us suffering from illness that can be avoided’. Of course patients are autonomous; they are at liberty to decline, without fear of causing offence, the advice that is offered, but it is the responsibility of the health professional to make certain that they are informed, and understand the issues. A general practice has a responsibility for each individual patient but it has also a wider responsibility to its whole population. We need to protect from infectious disease by immunizing the well; to detect early illness by measuring blood pressure, screening for cancer of the cervix or high blood cholesterol and to promote good health by considering diet, smoking, alcohol intake, exercise and relaxation in well people.

Why us and not someone else you may ask? We have two great assets on our side. Firstly most people see a doctor regularly. Every year nearly 70% of the people on our list will attend the surgery; by the end of two years that figure will have risen to 80% and by a further year to 90%. That provides a tremendous chance for opportunistic screening or advice giving, but if it is to be effective every person in the team needs to be alert to that chance. Secondly patients are ‘switched on’ to health concerns when they consult so health education makes a great impact at this time. Fear is a great force towards taking action to prevent ill health.

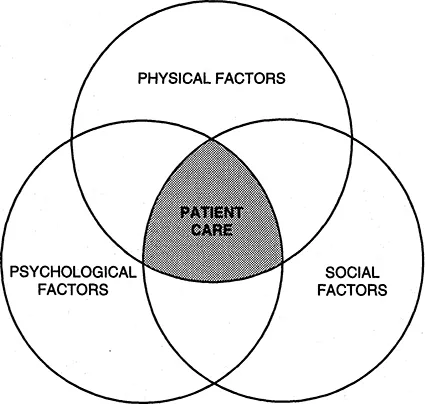

5 Care attends to the whole person. Wholism has become something of a cliché in the past few years and the concept has been grasped by others who have often accused the medical profession of being so disease-centred – ‘he was only interested in my liver’ – that they ignored the person outside the disease. There is some justification in this view in some of our behaviour but we have moved progressively further towards a much more rounded approach. We are now comfortable with this and have encapsulated the concept by constructing diagnoses or management plans in interlocking areas of physical, psychological and social factors.

Clearly at times, or with particular diseases one of these components is predominant. A young man with a fractured tibia has a largely physical problem, but even here there may be anxiety about his ability to play football in the future that constitutes a major worry and problems with his work of a social nature. If these are not considered he may rightly feel incompletely cared for. In other situations, such as malignant disease or depression other areas become predominant but they are all always there. Administration needs to grasp this idea if it is to recognize the different reasons for seeking care and the different patterns of behaviour of those who come.

Figure 1.1 The factors affecting patient care.

In 1969 the Royal College of General Practitioners published a job definition of the general practitioner and it is as true today as when it was first written.

Job definition

‘The general practitioner is a doctor who provides personal, primary and continuing medical care to individuals and families. He may attend his patients in their homes, in his consulting-room or sometimes in hospital. He accepts the responsibility for making an initial decision on every problem his patient may present to him, consulting with specialists when he thinks it appropriate to do so. He will usually work in a group with other general practitioners, from premises that are built or modified for the purpose, with the help of paramedical colleagues, adequate secretarial staff and all the equipment which is necessary. Even if he is in single-handed practice, he will work in a team and delegate when necessary. His diagnoses will be composed in physical, psychological and social terms. He will intervene educationally, preventively and therapeutically to promote his patient’s health.’

(From p.l of The Future General Practitioner, Royal College of General Practitioners, 1972.)

Family Health Services Authority

Most practice managers will already have a clear understanding of the structure of the practice within which they work so this chapter will not describe this but will concentrate, rather, on the ideas behind the structure and the way it is changing and will seek to explore some of the philosophy behind these changes. We shall describe briefly some of the outside organizations with which general practice relates as the new functions and structure of these may be less well-known to practice managers.

The general practitioner (GP) has a different relationship with the health service to that of doctors working in hospitals. He is not an employee of the health service as they are but an independent contractor. This is an important difference which shapes and directs the way in which general practice is managed and develops. To understand the concept of ‘independent contractor status’ it is helpful to use an analogy from the construction industry. The builder who has the task of developing a housing estate directly employs a number of workers who labour, lay bricks and work with timber. He also needs electricity put into these houses – wiring, plugs, cooker points and so on – but he does not directly employ electricians so he gives a contract to a firm of electricians to do this, specifying what is required and how much he will pay for the completed job but he leaves the details of the work to the ‘independent’ firm to arrange and only requires a satisfactory job to be done within the time and price agreed by the firm who is thus an ‘independent contractor’. In this same way the GP has a contract to supply services to patients who are registered by the Family Health Services Authority (FHSA) as on his list. It is his responsibility to provide the premises, time, equipment and systems required to do a proper job. There is considerable flexibility about how and where he does this providing that it is done within the broad guidelines of the contract.

An independent contractor is therefore a self-employed person who has entered into a contract for services with another party. This contract for services is fundamentally different from a contract of services, which governs employee-employer relationships and is explained in greater detail in Making Sense of the New Contract ed. J. Chisholm, Radcliffe Medical Press, Oxford (1990), but it is essentially a difference in the amount of control that exists.

The GP then is not an employee of the FHSA. If he makes a mistake the responsibility is his, not that of the FHSA. If he had been an employee then the employer, the FHSA, would also have been responsible if a mistake was made. Of course the contract agreed between the two parties is much more explicit than this and contains rules about hours of work and access by patients, about the standards of premises and where doctors may live, but much of the work is bound by general statements, such as ‘a doctor shall render his patients all necessary and appropriate personal services of the type usually provided by general practitioners’, or ‘shall keep adequate records of the illnesses and treatment of his patient on forms supplied to him for the purpose by the Authority’, or ‘shall do so at his premises or, if the condition of the patient so requires, elsewhere in his practice area’, etc. It will be noted at once that the use of words and phrases such as ‘necessary and appropriate’, ‘adequate’ and so on raise issues of what is adequate or necessary and by whom it is so judged.

The functions of the previous Family Practitioner Committee was mainly to administer the contract with doctors (and dentists, opticians and pharmacists) and to maintain the register of patients, and it had nearly half of its members drawn from professional bodies. With the new FHSAs this has changed. Why has this change been proposed? The answer lies partly within the concept of the independent contractor. The advantage of this system is, primarily, its flexibility. As practices can control their own methods and systems for providing care a good deal of variation occurs depending on local differences. Populations, patients, staff, buildings and local geography are all different and what suits one practice may not suit others. The potential disadvantage is that the variation may become too great. There may be such a variation that unacceptable standards are allowed to exist. The FHS...