![]()

1 Integration of Graphics Processing Cores with Microprocessors

Deepak C. Sekar and Chinnakrishnan Ballapuram

Contents

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Why Integrate Central Processing Units and Graphics Processing Units on the Same Chip?

1.3 Case Study of Integrated Central Processing Unit–Graphics Processing Unit Cores

1.3.1 AMD Llano

1.3.2 Intel Ivy Bridge

1.4 Technology Considerations

1.5 Power Management

1.6 System Architecture

1.7 Programming and Memory Models

1.8 Area and Power Implications in Accelerated Processing Units

1.9 Graphical Processing Units as First-Class Processors

1.10 Summary

References

1.1 Introduction

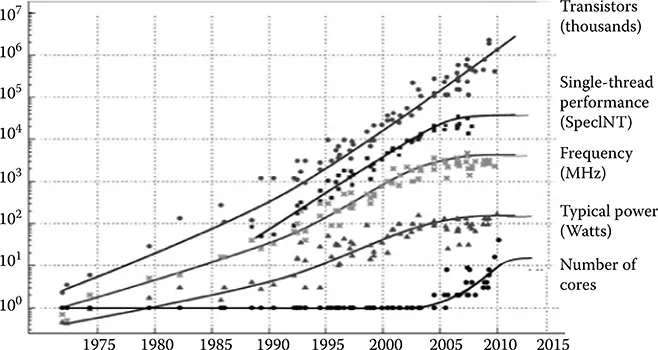

Power and thermal constraints have caused a paradigm shift in the semiconductor industry over the past few years. All market segments, including phones, tablets, desktops, and servers, have now reduced their emphasis on clock frequency and shifted to multicore architectures for boosting performance. Figure 1.1 clearly shows this trend of saturating frequency and increasing core count in modern processors. With Moore’s Law, on-die integration of many components such as peripheral control hubs, dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) controllers, modems, and more importantly graphics processors has become possible. Single-chip integration of graphics processing units (GPUs) with central processing units (CPUs) has emerged and also brought many challenges that arise from integrating disparate devices/architectures, starting from overall system architecture, software tools, programming and memory models, interconnect design, power and performance, transistor requirements, and process-related constraints. This chapter provides insight into the implementation, benefits and problems, current solutions, and future challenges of systems having CPUs and GPUs on the same chip.

FIGURE 1.1 Microprocessor trends over the past 35 years. (Naffziger, S., Technology impacts from the new wave of architectures for media-rich workloads, Symposium on VLSI Technology © 2011 IEEE.)

1.2 Why Integrate Central Processing Units and Graphics Processing Units on the Same Chip?

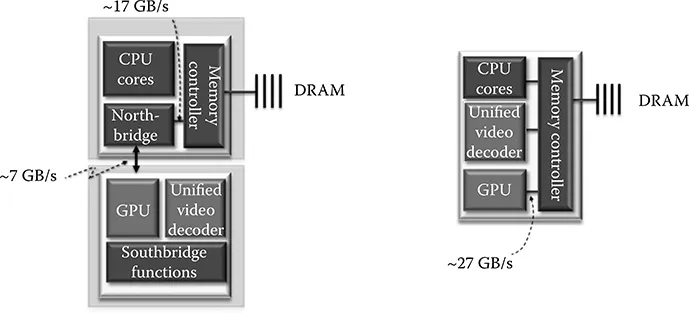

CPU and GPU microarchitecture have evolved over time, though the CPU progressed at a much faster pace as graphics technology came into prominence a bit later than the CPU. Graphics is now getting more attention through games, content consumption from devices such as tablets, bigger sized phones, smart TVs, and other mobile devices. Also, as the performance of the CPU has matured, additional transistors from process shrink are used to enhance 3D graphics and media performance, and integrate more disparate devices on the same die. Figure 1.2 compares a system having a discrete graphics chip with another having a GPU integrated on the same die as the CPU. The benefits of having an integrated GPU are immediately apparent [1]:

Bandwidth between the GPU and the DRAM is increased by almost three times. This improves performance quite significantly for bandwidth-hungry graphics functions.

Power and latency of interconnects between the CPU chip and the GPU chip (of the multichip solution) are reduced.

Data can be shared between the CPU and the GPU efficiently through better programming and memory models.

Many workloads stress the GPU or the CPU and not both simultaneously. For GPU-intensive workloads, part of the CPU power budget can be transferred to the GPU and vice versa. This allows better performance–power trade-offs for the system.

Besides these benefits, the trend of integrating GPUs with CPUs has an important scalability advantage. GPUs are inherently parallel and are known to benefit linearly with density improvements. Moore’s Law is excellent at providing density improvements, even though many argue that the performance and power improvements it used to provide have run out of steam. By integrating GPUs, the scalability of computing systems is expected to be better.

FIGURE 1.2 A multichip central processing unit–graphics processing unit solution (Left). A single-chip central processing unit–graphics processing unit solution (Right). (Naffziger, S., Technology impacts from the new wave of architectures for media-rich workloads, Symposium on VLSI Technology © 2011 IEEE.)

1.3 Case Study of Integrated Central Processing Unit–Graphics Processing Unit Cores

In this section, we describe two modern processors, AMD Llano (Advanced Micro Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and Intel Ivy Bridge (Intel, Santa Clara, CA), which have both integrated CPUs and GPUs on the same die. These chips are often referred to as accelerated processing units (APUs).

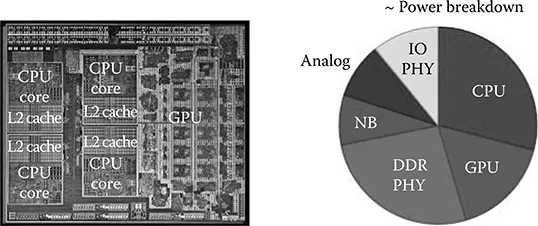

1.3.1 AMD Llano

The AMD Llano chip was constructed in a 32-nm high-k metal gate silicon-on-insulator technology [2]. Figure 1.3 shows the integrated die that includes four CPU cores, a graphics core, a unified video decoder, and memory and input/output (I/O) controllers. The total die area is 227 mm2. CPU cores were x86 based, with 1 MB of L2 cache allocated per core. Each CPU core was 17.7 mm2 including the L2 cache. Power gating was aggressively applied to both the core and the L2 cache to minimize power consumption. A dynamic voltage and frequency system (DVFS) was used that tuned supply voltage as a function of clock frequency to minimize power. Clock frequency was tuned for each core based on power consumption and activity of other CPU cores and the GPU. This was one of the key advantages of chip-level CPU and GPU integration—the power budget could be flexibly shared between these components based on workload and activity.

FIGURE 1.3 The 32-nm AMD Llano chip and a breakdown of its power consumption. IO PHY and DDR PHY denote interface circuits for input/outputs and dynamic random-access memory, respectively, and NB denotes the Northbridge.

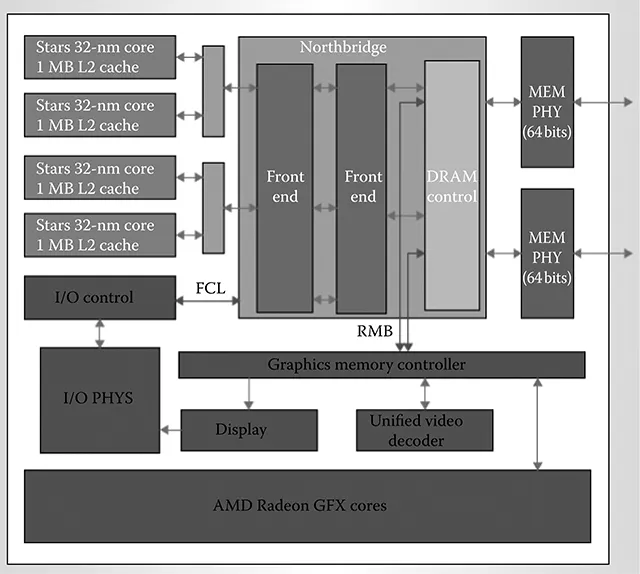

The GPU used a very long instruction word (VLIW) core as a basic building block, which included four stream cores, one special function stream core, one branch unit, and some general purpose registers. Each stream core could coissue a 32-bit multiply and dependent ADD in a single clock. Sixteen of these VLIW cores were combined to form a single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) processing unit. The GPU consisted of five such SIMDs, leading to a combined throughput of 480 billion floating point operations per second. Power gating was implemented in the GPU core as well, to save power. The GPU core occupied approximately 80 mm2, which was nearly 35% of the die area. Power consumption of the GPU was comparable to that of the CPU for many workloads, as shown in Figure 1.3. The CPU cores and the GPU shared a common memory in Llano systems, and a portion of this memory could be graphics frame buffer memory. Graphics, multimedia, and display memory traffic were routed through the graphics memory controller, which arbitrated between the requestors and issued a stream of memory requests over the Radeon Memory Bus to the Northbridge (Figure 1.4). Graphics memory controller accesses to frame buffer memory were noncoherent and did not snoop processor caches. Graphics or multimedia coherent accesses to memory were directed over the Fusion Control Link, which was also the path for processor access to I/O devices. The memory controller arbitrated between coherent and noncoherent accesses to memory.

1.3.2 Intel Ivy Bridge

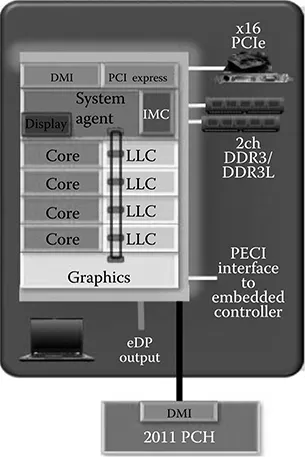

Ivy Bridge was a 22-nm product from Intel that integrated CPU and GPU cores on the same die [3]. The four x86 CPU cores and graphics core were connected through a ring interconnect and shared the memory controller. Ivy Bridge had 1.4 billion transistors and a die size of about 160 mm2. It was the first product that used a trigate transistor technology.

Figure 1.5 shows the system architecture of Ivy Bridge, where a graphics core occupied a significant portion of the total die. All coherent and noncoherent requests from both CPU and GPU were passed through the shared interconnect. The shared ring interconnect provided hundreds of GB/s bandwidth to the CPU and GPU cores. The last level cache is logically one, but physically distributed to independently deliver data.

FIGURE 1.4 Block diagram of the AMD Llano chip. FCL denotes Fusion Control Link, MEM denotes memory, PHY denotes physical layers, and RMB denotes Radeon Memory Bus.

In Llano, coherent requests from the GPU went through a coherent queue and the noncoherent requests directly went to the memory. In Ivy Bridge, the CPU and GPU could share data in the bigger L3 cache, for example. The CPU could write commands to the GPU through the L3 cache, and in turn the GPU could flush data back to the L3 cache for the CPU to access. Also, the bigger L3 cache reduced memory bandwidth requirements and hence led to overall lower power consumption. Two different varieties of GPU cores were developed to serve different market segments. The graphics performance is mainly determined by the number of shader cores. The lower end segment had eight shader cores in one slice, whereas the next level segment had two slices. Different components of the processor were on different power planes to dynamically turn on/off the segments based on demands to save power. The CPU, GPU, and system agent were on different power planes to dynamically perform DVFS.

1.4 Technology Considerations

The fundamentally different nature of CPU and GPU computations places interesting requirements on process and device technology [1]. CPUs rely on using high-performance components, whereas GPUs require high-density, low-power components. This leads to the use of performance-optimized standard cell libraries for CPU portions of a design and density-optimized standard cell libraries for GPU portions of a design. For example, the AMD Llano chip had 3.5 million flip-flops in its GPU, but only 0.66 million flip-flops in its CPU. The CPU flip-flops required higher performance and so were optimized differently. The flip-flop used for CPU cores occupied 50% more area than the flip-flop used for GPUs. The need for higher performance in CPU blocks led to the use of lower threshold voltages and channel lengths in CPU standard cell libraries compared to GPU ones.

FIGURE 1.5 Block diagram of the Intel Ivy Bridge chip.

The need for higher density in GPUs also leads to the requirement for smaller size wires than a pure-CPU process technology. Smaller size wiring causes more wire delay issues because wire resistivity increases exponentially at smaller dimensions. This is because of scattering at sidewalls and grain boundaries of wires as well as the fact that the diffusion barrier of copper occupies a bigger percentage of wire area.

In the long term, the differences in technology requirements for CPU and GPU cores could lead to 3D integration solutions. This would be particularly relevant for mobile applications where heat is less of a constraint. CPU cores could be stacked on a layer built with a high-performance process technology, whereas GPU cores could be stacked on a different layer built with a density-optimized process technology. DRAM could be stacked above these layers to provide the high memory bandwidth and low latency required for these systems. Figure 1.6 shows a schematic of such a system.

1.5 Power Management

Most workloads emphasize either the serial CPU or the GPU and do not heavily utilize both simultaneously. By dynamically monitoring the power consumption in each CPU and GPU, and tracking the thermal characteristics of the die, watts that go unused by one compute element can be utilized by others. This transfer of power, however, is a complex function of locality on the die and the thermal characteristics of the cooling solution. The efficiency of sharing is a function of where the hot spot is and will vary across the spectrum of power ...