![]()

p.27

1

SPACE

Empires, nations, borders

James Koranyi and Bernhard Struck1

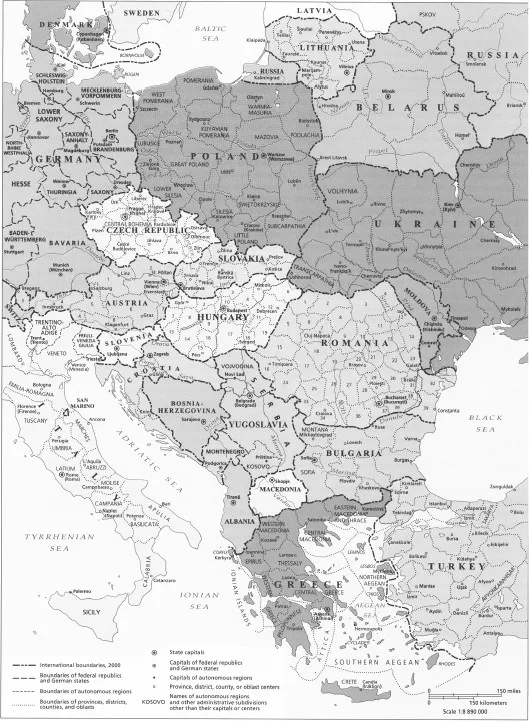

Maps offer powerful visual representations of space, since they tend to portray stability and the dominant spatial order at any given moment. For this reason a contemporary political map of East Central Europe would not present an accurate picture of long-term processes of state-building in the region. A glimpse at any recent school atlas would reveal twenty-one states on a political map of East Central Europe (Map 1.1). From north to south these include: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Russia, Belarus, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria, Hungary, Slovenia, Romania, Moldova, Ukraine, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Albania, and Greece. If one were to include neighbors and contested borderlands in Germany, Turkey, Finland, Cyprus, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Austria, or Russia, this would complicate matters further.2

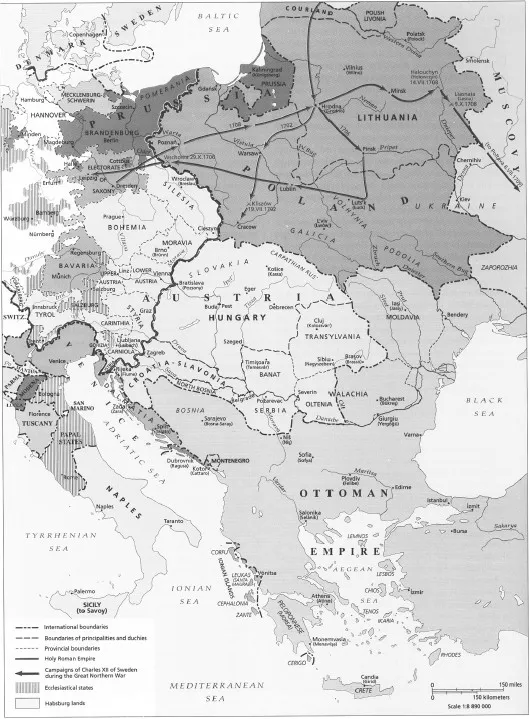

Consider, by contrast, a political map of this region in 1740 (Map 1.2). This would show only three dominant geopolitical powers in the region: the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Habsburg Empire and the Ottoman Empire. At the margins were four others: Brandenburg-Prussia, Russia of Tsar Peter the Great (who was soon to assume the title of “emperor”), Sweden, and Venice.3 Two of the three dominant powers were to vanish from the map in the course of time. Poland-Lithuania was partitioned in the late eighteenth century, regaining independence only in 1918 on less territory and as two separate states: Poland and Lithuania. The Ottoman Empire’s influence over the region initially diminished slowly, then at a more rapid pace from the 1860s on. Scandinavia no longer constitutes a part of our mental map of East Central Europe.4 Yet, around 1700 Sweden was a major regional player, exemplified by Charles XII’s extended military campaigns in Poland-Lithuania and Russia during the Great Northern War in the early eighteenth century.5 Spatial concepts such as Scandinavia, the West, Mitteleuropa, the Balkans, or Eastern Europe all have specific origins and histories. Neither “Eastern Europe” nor “Scandinavia” existed in 1700 and only emerged in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century according to some accounts.6 Focusing on space and territories, this chapter explores how and when imperial and nation-state borders, as well as spheres of influence appeared in this region from roughly 1700 to the present.

The juxtaposition of the two maps of the region illustrates the drastic territorial changes and the shift in borders – and thus of the populations these encompassed – in East Central Europe over the past 300 years. Such a long-term perspective reveals that the multitude of independent states that we find today has not been the historical norm, but rather a relatively recent development with its roots in the second half of the nineteenth century. The break-up of multinational empires after 1918 and of smaller states at the end of the Cold War has contributed to the proliferation of polities in East Central Europe. As the last part of this chapter argues, both these ruptures belong to a single regime of territoriality, which started around 1860.

p.28

p.29

p.30

Regimes of territoriality and the problem of periodization

Space and related spatial concepts, such as “East,” “West,” “Orient,” or “the Balkans” through which we make sense of space, are not neutral. Space is not both absolute, and relative and relational. Space can be interpreted as absolute in geography or cartography. Geodetic surveys measure spatial relations and collect geographical data based on mathematical operations, and they translate these into two-dimensional maps. Such mapmaking takes the idea of absolute space as its foundation. Absolute space can be imagined, measured, and divided through cartography, statistics, and other forms of (spatial) knowledge. Such knowledge provides the basis for claims of state sovereignty and serves as an essential tool for control over a certain territory.7

Territories are of course nothing new to historians. On the contrary, they are arguably the most common geographic framework for their work. However, the problem at stake in this chapter is not so much a history of territories as a history of territory as political process in East Central Europe. Territories – at least in modern Europe – are more than sections of the Earth belonging to this or that political entity. They are also expressions of what Charles Maier has called “territoriality.” Put briefly, this term describes the combined apparatus of political, economic, scientific, technological, and ideological systems developed in Europe since the early sixteenth century to define and preserve exclusive sovereignty over more or less precisely bounded spatial entities. Along these lines, Maier calls a territory a “space with a border that allows effective control of public and political life,” and, since roughly the mid-1600s, the fundamental premise of state authority.8

While complex and all-embracing, territoriality is not a static concept; it is sensitive to the evolution of historical structures on a grand scale, and so Maier (with reference to Thomas Kuhn’s scientific paradigm and Michel Foucault’s épistème) periodizes its shifts into “regimes.”9 According to Maier, there have been four territorial regimes between 1519 and the present, three of these from 1700 to the present; thus they provide a useful framing device for our analysis. The period between the mid-seventeenth century and the last decade of the eighteenth century is marked by two overlapping sub-regimes of territoriality. The “dynastic/territorial” regime (1650–1780), and the “cadastral” regime (1720–90) help us make sense of Enlightened absolutist reforms affecting East Central Europe in the first three-quarters of the eighteenth century and the destruction of Poland-Lithuania in the final decades of the century. The next regime arrived on the heels of the French Revolution following the crisis of the Old Regime that unfolded between roughly 1780 and 1840. Then a new regime, the Federal/Central (1850–80) gradially gave birth to the nation-state. Between 1880 and 1980, this regime became deeply entrenched within state borders as imperial rivalry spread it across the globe. The fourth – and possibly final – regime, Maier argues, began in the mid-1960s. He tentatively calls it the “Post-Territorial” regime and suggests that it heralds the obsolescence of territoriality altogether.10

p.31

Here, we simplify Charles Maier’s complex periodization of regimes of territoriality by examining only two distinct periods in the making of modern East Central European geopolitical space. The first period runs from the 1700s to the 1860s, and the second from the 1860s to the 1960s. It was in the second era that Eastern Europe was constructed as a region. Thereafter, East Central European space became largely subsumed into global structures. The outcome of this current period is still unclear and open-ended. This way of carving up time allows us to apply a transnational approach, to identify broad trends in the history of the region, and to account for the shifts in the mental map of the region – that is, how it was perceived by outsiders and insiders – from one period to another.

Throughout, it is important to note that East Central Europe’s history unfolded in conjunction with Western European and global trends, but also autonomously from them. It is thus clear that the political history of East Central Europe must not merely be modeled on a problematic Western standard, but should also be thought of in imaginative and regionally specific ways.11 One of the challenges of transnational and global history is to find spatial frameworks and entities that can supplement the nation-state in established historical explanation. This then also casts a different light on chronological conventions by exploring what lies beyond the national framework.12

Periodization is to some extent an arbitrary exercise. However, historical periods are a key heuristic and analytical tool through which people interpret the past. National histories generally follow important national events. In Polish historiography, for instance, the years of “national disasters” (1772, 1795) or failed national rebellions (1830, 1863) are important chronological markers. These are joined by the major international events that comprise the classic milestones of European history: 1815, 1914–18, 1939–45, and 1989–91. We have tried to find a periodization that goes beyond these national and international frameworks as it is a goal of this chapter to provide a still different – transnational – way of understanding East Central Europe.13 Transnational analyses of the region’s space, and the corresponding longue durée periodization, challenge normative ways of understanding its history. We have thus deliberately avoided seeing “big” international events as total caesuras. While 1815...