eBook - ePub

Managing Emotions in the Workplace

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Emotions in the Workplace

About this book

The modern workplace is often thought of as cold and rational, as no place for the experience and expression of emotions. Yet it is no more emotionless than any other aspect of life. Individuals bring their affective states and emotional "buttons" to work, leaders try to engender feelings of passion and enthusiasm for the organization and its mission, and consultants seek to increase job satisfaction, commitment, and trust. This book advances the understanding of the causes and effects of emotions at work and extends existing theories to consider implications for the management of emotions. The international cast of authors examines the practical issues raised when organizations are studied as places where emotions are aroused, suppressed, used, and avoided. This book also joins the debate on how organizations and individuals ought to manage emotions in the workplace. Managing Emotions in the Workplace is designed for use in graduate level courses in Organizational Behavior, Human Resource Management, or Organizational Development - any course in which the role of emotions in the workplace is a central concern. Scholars and consultants will also find this book to be an essential resource on the latest theory and practice in this emerging field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing Emotions in the Workplace by Neal M. Ashkanasy,Wilfred J. Zerbe,Charmine E. J. Hartel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

MANAGING EMOTIONS IN A CHANGING WORKPLACE

Introduction

The modern workplace is often thought of as cold and rational, as no place for the experience and expression of emotions. Yet it is no more emotionless than any other aspect of social life (Ashforth and Humphrey 1995; Ashkanasy, Härtel, and Zerbe 2000b; Fisher and Ashkanasy 2000). Individuals bring their affective states and traits and emotional “buttons” to work; leaders try to engender in followers feelings of passion and enthusiasm for the organization and its well-being; groups speak of esprit de corps; and organizational consultants seek to increase job satisfaction, commitment, trust, and loyalty. Organizational members seldom carry out their work in an objective fashion based on cold, cognitive calculation. Instead, as Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) argue, workplace experiences comprise a succession of work events that can be pleasing and invigorating, or stressful and frustrating. Without a doubt, emotions are an inherent part of the workplace.

In recent years, we have witnessed a rise in the organized study of emotions in the workplace. The editors of this book have been at the forefront of this rise, including the publication of Emotions in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Practice (Ashkanasy, Härtel, and Zerbe 2000a), the forerunner to the present volume. Ashkanasy was also guest editor (with Cynthia Fisher) of a Special Issue of the Journal of Organizational Behavior on this topic. Other books that are contributing to this rise are by Fineman (2000); Ciarrochi, Forgas, and Mayer (2001); Lord, Klimoski, and Kanfer (2001); and Payne and Cooper (2001); and special editions of Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes (Weiss 2001) and Leadership Quarterly (Humphrey, planned for 2002). An additional book is in preparation by Weiss, Cropanzano, and Ashkanasy (in press). Finally, the renewed interest is evident in the strong support of the biannual Conferences on Emotions and Organizational Life, chaired by the editors of the present volume. Collectively, these publications and activities are advancing our understanding of the causes and effects of emotions at work.

In this volume, we focus on extending theory about emotions in the workplace to consider specifically the implications for the management of emotions in today’s changing workplace. We ask: What are the practical issues that are raised when we acknowledge organizations as places where emotions are aroused and suppressed, displayed and contained, used to achieve organizational goals and avoided in the hope of preventing discomfort or harm? We also explore in this book the debate on how organizations and individuals ought to manage emotions in the modern workplace.

Although the workplace emotions literature is growing, it is still a young area of study. As such it is characterized by diversity in theoretical orientation and topical focus. It also enjoys diversity of methodological practice, which some literatures experience only as they mature. It is difficult, therefore, to specify an all-encompassing yet parsimonious system that categorizes work in the field. At the same time, four domains capture a good deal of the area: (1) Affective Events Theory (Weiss and Cropanzano 1996), which is premised on the idea that everyday hassles and uplifts determine emotional states at work, has been proposed as an overarching model of emotions in organizations; (2) Emotional Labor deals with the question of why and how employees may display particular emotions, including emotions that differ from how they feel, and the effects of such labor (see Hochschild 1979); (3) Mood Theory examines the idea that positive and negative mood states can determine organizational members’ attitudes and behaviors (e.g., George and Brief 1996a); and (4) Emotional Intelligence refers to the ability to read emotions in one’s self and others and to be able to use this information to guide decision making (see Goleman 1998b; Mayer and Salovey 1993; 1995; 1997; Salovey and Mayer 1990). We will discuss recent developments in each of these areas in turn, as a means to set the scene for the chapters that follow. Following this background, we will briefly summarize the chapters in each of the four sections of this book.

Affective Events Theory

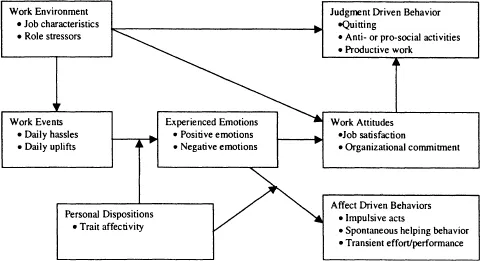

While there is yet to be an all-encompassing theory of emotions in workplace settings, affective events theory (AET) comes closest. Indeed, until Weiss and Cropanzano published their seminal paper on this topic in 1996, there was little in the organizational science literature that enabled scholars to appreciate properly the role of emotions. In AET, Weiss and Cropanzano argue that aspects of the work environment, including environmental conditions, roles, and job design, initiate emotions in organizational settings. These aspects of work thus constitute the “affective events,” described colloquially as “hassles and uplifts” (Basch and Fisher 2000), that act systematically to determine affective states. These states, in turn, lead to attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Emotions can also directly lead to behavioral outcomes such as productive work (see Wright, Bonett, and Sweeney 1993; Wright and Cropanzano 1998), pro- or antisocial actions (Organ 1990), or turnover behavior. AET also incorporates trait affectivity, a personal disposition that conditions the formation of positive and negative emotions. AET is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

From the perspective of the current volume, which deals with managing emotions in workplace settings, AET is of critical significance. It tells us that organizational characteristics and managerial policies can affect the emotional states of organizational members, and that these, in turn, can affect members’ attitudes and performance. Although Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) initially presented their model as an untested theory, and research is still in early stages, results to date have been strongly supportive of the core ideas in the theory. Examples of studies to date include Fisher (2000); O’Shea, Ashkanasy, Gallois, and Härtel (1999; 2000a, b); Fisher and Noble (2000); and Weiss, Nicholas, and Daus (1999). These studies have all supported the idea that emotional states mediate the effect of work events on outcomes. In particular, they have shown that including measures of emotional states brings once elusive relationships between work events and work outcomes into focus. These emotional states encompass both mood, the rather generalized feelings of happiness or sadness that we all experience from time to time; and more specific emotional states, such as joy, pride, fear, anger, or disgust, that result from specific occurrences in our environment (see Russell and Feldman-Barrett 1999).

One of the more important outcomes of AET research is a new understanding of job satisfaction. For many years, researchers have been stumped by consistent findings that whether work performance is high or low, it bears no relation to workers’ feelings of satisfaction (see Wright and Staw 1999, for discussion). These findings, however, seem to fly in the face of what managers see every day—that, by and large, satisfied workers are productive workers. In AET, however, attitudes and affective states relating to job satisfaction are viewed as separable (Fisher 2000). Accordingly, researchers today (e.g., Brief and Roberson 1989; Fisher 2000; Weiss, Nicholas, and Daus 1999) have argued that job satisfaction constitutes a set of attitudes toward work that do not necessarily include affective feelings. Indeed, in our previous volume we argued that whereas attitudes are evaluations about objects, such as one’s job, emotions are evaluations of oneself; they are appraisals of one’s own well-being (Zerbe, Härtel and Ashkanasy 2000; see also Cropanzano, Weiss, Suckow, and Grandey 2000). Further, AET makes it clear that many emotions are transient states rather than aspects of work life that remain constant for long periods of time. Employees at work can be overjoyed with a successful outcome one moment and be disappointed and perhaps even angry in the next moment when their boss does not appear to share their enthusiasm. In a recent study, Fisher and Noble (2000) demonstrated for the first time that satisfaction and performance are, indeed, strongly related on a moment-to-moment basis in employees’ work lives, although they still appear to be unrelated when looked at over a longer period of time. Fisher and Noble argue that researchers have been looking in the wrong place for the satisfaction-performance link that managers report; instead of looking “between-people,” researchers need to study “within-person” effects.

In effect, AET and the empirical findings that have been obtained so far are revolutionizing our view of behavior in organizations. We now know that behavior and performance of employees at work are not defined by job satisfaction as was traditionally thought. Instead, employees’ behaviors and attitudes are constantly changing as they encounter everyday hassles and uplifts in their workplace (see Fisher 2000; Fisher and Noble 2000; Hodges and Wilson 1993).

In summary, AET has alerted researchers and managers alike to the importance of emotional states in organizational settings. In particular, the emotions that employees experience as a result of the everyday events that happen to them are now seen to be a central aspect of understanding employee attitudes and behavior. Further, Fisher (1998, 2000; see also Fisher and Noble 2000) has argued that it is the little things that can add up to determine how employees think and behave. In effect, it is the frequency with which these events occur, and the accumulation of events, rather than the intensity of particular events that determine the ultimate outcomes. Thus, while employees may be able to deal with one or two major events, they have more difficulty when adverse events unremittingly affect the way that they work, even if the events appear to be relatively minor. Importantly, however, the results also suggest that uplifting events, such as a complementary comment by a superior, or a friendly and supportive act by a colleague following a negative occurrence, such as a lost sale, can reverse the negative consequences that would normally be expected to flow from the event (see Grzywacz and Marks 2000).

Emotional Labor

The second topic we address is emotional labor. Emotional labor occurs when employees are required to display particular emotional states as a part of their job. Beginning with Hochschild (1983), emotional labor research has been the traditional flag bearer of research into emotions in organizations. According to Hoschchild (see also Rafaeli and Sutton 1987, 1989), employees in service industries, such as airline cabin crews, shop assistants, funeral directors, and even debt collectors, are required by their jobs to maintain particular displays of emotions. Flight attendants, for example, are supposed to smile at their customers, while funeral directors and police officers and debt collectors need to maintain the appropriate displays of negative emotion. More recently, the concept of emotional labor has been extended to include emotional displays by employees within the organization. For example, norms exist as to how employees relate to each other in work and social situations (see Humphrey 2000; Kruml and Geddes 2000).

One of the more powerful effects of emotional labor concerns what happens when there is a discrepancy between the emotions felt and those that a job requires a worker to display to conform to role expectations. Service workers, in particular, often find themselves in this predicament. Hochschild (1983) coined the term emotional dissonance to characterize this situation. She describes some typical incidents in her analysis of flight attendants, where the attendants were even found to engage in acts of retribution against customers because of the buildup of repressed emotions. Mann (1999) argues that this sort of repressed emotional energy has negative consequences for employees in general. Indeed, Ashkanasy, Fisher, and Härtel (1998) point out that such instances of emotional dissonance constitute affective events, and thus trigger an AET train of reactions, leading eventually to performance outcomes for employees. In this respect, there has been a good deal of attention paid to emotional labor and its effects on employee well-being and its consequences for organizational performance (see Schaubroeck and Jones 2000; Tews and Glomb 2000; Wharton and Erickson 1995).

From the perspective of the present volume, the implications of emotional labor for managing emotions in organizations are clear. This is especially so in the instance of so-called service encounters—where organizational members are providing service directly to the organization’s clients or customers. In some of the seminal studies of emotional labor, Rafaeli and Sutton (1987, 1989; see also Sutton and Rafaeli 1988) showed that service employees’ displays of positive emotion (e.g., smiling) were directly related to positive customer reactions and, hence, to sales and organizational effectiveness. This pattern, however, was not always found. In one study, for example, Sutton and Rafaeli (1988) found an inverse relationship between sales and smiling. They determined that clerks had more time to socialize with customers in shops with low sales whereas, in the high sales shops, there was no time for such niceties. Sutton and Rafaeli coined the term Manhattan Effect to describe the resulting (unexpected) negative relationship between sales volume and smiling.

In fact, it is in customer service quality that emotional labor has the strongest ramifications. Schneider and Bowen (1985), for example, argue that employees’ attitudes and the attendant perceptions of service by customers are critical for maintenance of both individual and organizational performance. For example, in recent research that looked at emotional labor by bank clerks, Pugh (2001), found a positive relationship between positive displays of emotion and ratings of service quality. Pugh found, in particular, that the attitudes expressed by employees and evident in employees’ faces can create favorable or unfavorable impressions in customers’ minds, and negative attitudes could similarly engender unfavorable impressions (see also Härtel, Gough, and Härtel in press; Schneider, Parkington, and Buxton 1980). Other authors have argued that emotional intelligence may be a critical determinant of service providers’ ability to produce positive attitudes, intentions, and behaviors in consumers (Härtel, Barker, and Baker 1999). Another aspect of emotional expression in service settings is emotional contagion (Hatfield, Cacioppo, and Rapson 1994), which is the tendency of observers to become “infected” with the emotional state expressed by actors. Verbeke (1997), for example, showed that customers in service settings tended to mimic the emotional tone of the service employees. From a manager’s perspective, the imperative to ensure that employees in service jobs present the appropriate emotional expressions to customers is clear. In this regard, service employees have a special duty to ensure customer retention and satisfaction thorough appropriate emotion management. At the same time, managers need to ensure that the stress of emotional labor is not detrimental to employee performance (see Mann 1999).

Even as emotional labor can create economic benefits for organizations, it can have negative consequences on both the physical and the mental health of employees (see Mann 1999). The types of pent-up emotional outbursts described by Hochschild (1983), for example, result from a constant demand to manage emotions, and also to monitor the degree of felt emotional states. In the end, the strain of emotional labor can even lead to employee burnout (Kruml and Geddes 2000; Grandey 1998), and even physical symptoms (Parker and Wall 1998). Grandey (2000) and Schaubroeck and Jones (2000), for example, show that emotional strain leads to a weakened immune system and can result in fatigue, and, farther down the line, life-threatening diseases such as hypertension and cancer.

Faced with a discrepancy between felt emotions and those they “must” express, one way employees can choose to reduce this discrepancy is by displaying emotions closer to their feelings, even if this represents deviance from organizational norms. Alternatively they can seek to change their felt mood states. Tews and Glomb (2000) and Grandey (2000) argue that, if the dissonance can be reduced in this manner, then the resulting effect can even be positive, rather than negative. Hochschild, however, would argue that the long-term effect of such emotion management is alienation from the self. The implication for managers is that workplaces should be designed so that the feelings they create match those that employees are expected to express.

Emotional contagion may play a role in creating positive emotional environments. Research by Barsade (in press) and Bartel and Saavedra (2000) has found that even one member’s positive emotional display can initiate positive emotions among work group members, leading to greater group cooperativeness, less group conflict, and positive perceptions of individual task performance (see also Härtel, Gough, and Härtel in press). Barsade concluded from her study that managers have a special role to play in this respect, namely, themselves displaying positive affect that carries through to socialization processes and the group’s culture. Ashkanasy and Tse (2000) also stress the importance of managers’ displays and management of positive emotion in engendering higher levels of group effectiveness and productivity.

In summary, although there is still scope for further research into the antecedents and consequences of emotional labor, the indications to date, beginning with Hochschild’s (1983) research, are that emotional labor is a critical component of employee effectiveness. Recent research has extended the early findings in service settings to encompass everyday interactions at work. In this sense, emotional labor becomes another source of affective events that need to be managed if the full potential of individual and organizational work outcomes is to be realized.

Mood Effects in Organizations

The third topic we address in this introduction is mood in organizational settings. Moods differ from emotions in that they are more diffuse and longer lasting. Consistent with AET, recent research has demonstrated that both positive and negative moods affect the way employees think and behave at work (see George and Brief 1996a; Isen 1999). Research into mood in organizations began in the early 1990s (e.g., George and Brief 1992; Isen and Baron 1991), at around the same time as mood research...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Half Title

- 1 Managing Emotions in a Changing Workplace

- I Change!!

- II Conflict/Interpersonal!!

- III Decision Making!!

- IV Emotional Labor!!

- References

- About the Editors and Contributors

- Index