eBook - ePub

Fluid Therapy for the Surgical Patient

- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fluid Therapy for the Surgical Patient

About this book

Over the past decade, there have been a large number of important studies related to fluid management for the surgical patient, resulting in confusion on this critical aspect of patient care. Proper fluid therapy in the perioperative setting has always been important but has only recently had concrete outcome-based guidelines. This is the first comprehensive, up-to-date and practical summary book on the topic.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fluid Therapy for the Surgical Patient by Christer H. Svensen, Donald S. Prough, Liane Feldman, TJ Gan, Christer H. Svensen,Donald S. Prough,Liane Feldman,TJ Gan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medizin & Anästhesiologie & Schmerztherapie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Medizinchapter one

Fluid balance, regulatory mechanisms, and electrolytes

Mats Rundgren

Karolinska Institutet

Stockholm, Sweden

Christer H. Svensen

Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm South General Hospital

Stockholm, Sweden

Contents

1.1 Water

1.1.1 Distribution

1.1.2 Turnover

1.2 Electrolytes

1.3 Sodium (Na+)

1.3.1 Distribution

1.3.2 Normal intake

1.3.3 Excretion

1.4 Potassium (K+)

1.4.1 Distribution

1.4.2 Excretion

1.5 Fluid exchange across the cell membrane (between ECF and ICF)

1.6 Exchange across blood vessels (between plasma and ISF)

1.6.1 Glycocalyx—revised version of the Starling principles

1.7 Disturbances and compensatory mechanisms

1.8 Hormonal compensatory mechanisms

1.8.1 Vasopressin

1.8.1.1 Effects

1.8.1.2 Regulation

1.8.1.3 Pathophysiology

1.8.1.3.1 Diabetes insipidus

1.8.1.3.2 Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

1.8.2 Renin–angiotensin system

1.8.2.1 Effects

1.8.2.2 Regulation

1.8.2.3 Pathophysiology

1.8.3 Aldosterone

1.8.3.1 Regulation

1.8.3.2 Pathophysiology

1.8.4 Natriuretic peptides

1.8.4.1 Effects

1.8.4.2 Pathophysiology

1.9 Nonhormonal compensatory mechanisms

1.9.1 Water intake

1.9.2 Sodium intake

References

Key points

- Total body water (TBW) is divided into the following compartments (spaces):

- Intracellular fluid space (ICF)—about two-thirds of TBW.

- Extracellular fluid space (ECF)—about one-third of TBW, which in turn is divided into the following:

- – Interstitial fluid space (ISF)—about three-quarters of the ECF.

- – Intravascular fluid space (IVS)—about one-quarter of the ECF.

- The quantitatively most important electrolytes are sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), calcium (Ca2+), magnesium (Mg2+), phosphate, sulfate, and chloride (Cl–).

- The amount of Na+ in the body determines the ECF volume. The distribution of fluid between the intravascular and extravascular compartments is decisive for the plasma volume.

- The approach taken by Starling to describe the movement of fluids across the endothelial wall is now known to be too simplistic. The endothelium consists of a thin layer of cells with an inner fragile layer, the endothelial glycocalyx, which contains glucose aminoglycans amongst other components. This layer, easily destroyed, is decisive for vascular barrier persistence.

- Hormonal compensatory mechanisms take great part in fluid distribution.

1.1 Water

Fluid balance in a general sense involves the metabolism of water and electrolytes. The well-being of all cells places demands on the surrounding (extracellular) as well as the interior (intracellular) environment. It is important that there is a stable body fluid osmolality, or rather tonicity, regulating cell volume, which in turn appears to affect many cellular functions. The ECF is determined by the amount of body sodium (Na+), while the body fluid osmolality mainly reflects water metabolism. This chapter focuses on the turnover of water and Na+, the regulation of body fluid osmolality and ECF volume, and factors influencing the interchange of water between fluid compartments.

1.1.1 Distribution

The body water is distributed between different fluid compartments, or rather spaces. Water transport is mainly governed by tonicity gradients (from lower to higher) but also via hydrostatic pressure gradients (from higher to lower). The two major fluid spaces, the intracellular (ICF) and extracellular (ECF) fluid spaces, are separated by the cell membrane.

Somewhat surprisingly, the effect of cell volume on cellular function has rarely been investigated. The ability of many kinds of cells to change their intracellular tonicity in anisotonic environments, and thereby actively regulate their own volume, reflects the functional importance of cell volume. Most importantly, it is a phenomenon that should be considered in the treatment of both hyper- and hypo-osmolar conditions. The cell membranes are generally sufficiently water permeable for slow passage of water needed for leveling out osmotic gradients between ICF and ECF. Higher water exchange volume is facilitated by specific water channels (aquaporins). These channels are ubiquitously distributed but are mainly expressed in epithelia (kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, airways, and exocrine glands) and in capillary endothelial cells. The epithelia of collecting ducts in the kidneys constitute a unique part where the water permeability is hormonally controlled by antidiuretic hormone (vasopressin) [1].

The other barrier separates the intra- and extravascular (interstitial fluid, ISF) parts of the ECF space and is made up of the wall of the exchange blood vessels (capillaries and postcapillary venules). The fluid exchange across this barrier is dependent on both osmotic and hydrostatic forces. It is appropriate to consider the characteristics of the barrier, that is, the walls of the exchange vessels, which may vary in different parts of the body, as well as in different pathological states such as inflammation. In principal, this may also be true for the cell membrane in general but less apparent than in different parts of the cardiovascular system [2].

The total body water (TBW) is divided into the following spaces:

- ICF—about two-thirds of TBW

- ECF—about one-third of TBW

The ECF is divided into

- ISF—about three-quarters of the ECF

- Intravascular fluid (IVS), where plasma water is the water component of plasma volume (PV)—about one-quarter of the ECF

An additional part of the ECF, not included above, is the transcellular fluid, which is separated from the ISF by epithelia. These are fluid spaces (approximately 1 L in adults) that contain cerebrospinal fluid, joint fluid, and eye chamber fluid. Being surrounded by epithelia with different transport capacities and permeability characteristics, transcellular fluid usually has a quite different composition than the rest of the ECF. The transcellular fluid is not included in fluid balance calculations.

Large variations of water content of different tissues are obvious. The main reason for the variability in the TBW percentage of the body weight is the amount of fat tissue. The variability of TBW related to body weight is about 45%–70%. This raises the question whether fluid therapy calculations ought to be based on lean body mass, rather than total body weight. Women have somewhat lower TBW in relation to body weight due to more subcutaneous fat. With increasing age TBW decreases, mainly reflecting tissue atrophy (cell mass reduction). Infants have a much higher TBW percentage of b.w. (80%), mainly due to a higher ECF volume. Towards puberty, TBW gradually decreases towards adult conditions, with by far the greatest change occurring during the first year of life.

1.1.2 Turnover

The daily water turnover is about 40 mL/kg body weight in a healthy adult. This corresponds to more than 2.5 L in an individual weighing 70 kg. Variations are usually quite extensive without obvious reasons like body and environmental temperature and physical activity. Intake of water is usually more governed by food and drinking habits, rather than “physiological” need due to dehydration. Most people drink in advance, and the kidneys normally maintain the water balance via a controlled excretion of water [3]. The urine production is determined by the appropriate quantity of water, electrolytes, and metabolites needed to balance intake/production and the renal concentrating capacity. Water is lost from the body via several different routes like the skin, airways, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. The urine is normally the major route for excretion of water and electrolytes and many of the regulatory mechanisms target renal function. A common cause for increased water loss is elevated body temperature during fever or hyperthermia. Usually, a 10% increase in water loss per degree C elevation of body temperature is considered. The change is highly dependent on environmental factors such as ambient temperature, humidity, and dressing and therefore is a rather uncertain parameter. During hyperthermia and profuse sweating, the correlation between body temperature and water loss is even more unreliable.

In infants, the daily water turnover is much higher compared to adults (about 100–150 mL/kg body weight/day). Contributing factors are a larger skin area for evaporation in relation to body mass, a higher metabolic rate, and a reduced urinary concentrating ability. This should normalize to adult conditions around puberty.

1.2 Electrolytes

The quantitatively most important electrolytes are sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), calcium (Ca2+), magnesium (Mg2+), phosphate (several forms), sulfate (several forms), and chloride (Cl–). These ions constitute slightly more than 80% of the inorganic material in the body. A characteristic feature, as the term implies, is their electric charge. In many contexts, among them fluid balance, it is therefore more relevant to talk about positively (cations) and negatively (anions) charged ions and additionally include some organic substances. The physiologically most important cations are Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and H+ (strictly speaking H3O+). Correspondingly, important anions are Cl–, HCO3– och phosphate (mostly as HPO42–). It is also important to recall that proteins have many negative charges at the pH levels present in body fluids.

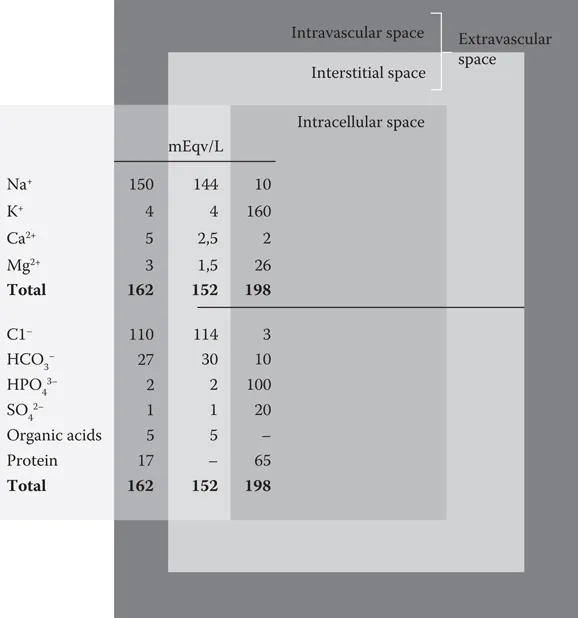

The electrolyte composition of the body fluid spaces is commonly depicted in a Gamble diagram, where the concentrations are expressed as mEq/L, to make clear that the number of positive and negative charges is the same within a fluid space (electroneutrality). A somewhat more lucid illustration of the electrolyte composition of the fluid spaces is given in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Electrolyte composition of body fluid spaces.

Electrolytes have structural (e.g., calcium and phosphate in bone tissue) as well as biochemical (almost all electrolytes) cellular functions. The metabolism of each electrolyte is effectively controlled, usually with involvement of hormones. Regulatory mechanisms are mainly involved in control of urinary excretion. So far no precise control of intake of any electrolyte has been observed in humans, although increased appetite for salt (NaCl) may appear in sodium deficiency. It is anyway far less accurate than that observed in many mammals, mainly herbivores. For calcium, and to some extent phosphate, the degree of intestinal absorption is under regulatory control. Another principal aspect is that the extracellular concentration of certain electrolytes (mainly Ca2+ and K+) influences cell excitability. This may have acute serious effects on nerves, heart, and skeletal muscle. The influence on excretion or intake would be too slow, and therefore mechanisms are available to influence distribution between body fluid compartments, like insulin- or epinephrine-induced cellular uptake of K+ in acute hyperkalem...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Editors

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 Fluid balance, regulatory mechanisms, and electrolytes

- Chapter 2 Infusion fluids

- Chapter 3 Perioperative fluid therapy: A general overview

- Chapter 4 Goal-directed fluid therapy: Use of invasive and semi-invasive devices

- Chapter 5 Monitoring the microcirculation

- Chapter 6 Noninvasive hemodynamic monitoring

- Chapter 7 Fluid therapy for the high-risk patient undergoing surgery

- Chapter 8 Fluid therapy for the trauma patient

- Chapter 9 Fluid management in the ambulatory surgery, gynecologic, and obstetric patient

- Chapter 10 Perioperative fluid management in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: Focus on enhanced recovery programs after surgery

- Chapter 11 Pediatric fluid therapy

- Chapter 12 Burn resuscitation

- Chapter 13 Fluid therapy in the intensive care unit, with a special focus on sepsis

- Chapter 14 Fluid therapy for the cardiothoracic patient

- Chapter 15 Fluid management in neurosurgical patients

- Index