- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Dynamic Documents with R and knitr

About this book

Quickly and Easily Write Dynamic Documents

Suitable for both beginners and advanced users, Dynamic Documents with R and knitr, Second Edition makes writing statistical reports easier by integrating computing directly with reporting. Reports range from homework, projects, exams, books, blogs, and web pages to virtually any documents related to statistical graphics, computing, and data analysis. The book covers basic applications for beginners while guiding power users in understanding the extensibility of the knitr package.

New to the Second Edition

- A new chapter that introduces R Markdown v2

- Changes that reflect improvements in the knitr package

- New sections on generating tables, defining custom printing methods for objects in code chunks, the C/Fortran engines, the Stan engine, running engines in a persistent session, and starting a local server to serve dynamic documents

Boost Your Productivity in Statistical Report Writing and Make Your Scientific Computing with R Reproducible

Like its highly praised predecessor, this edition shows you how to improve your efficiency in writing reports. The book takes you from program output to publication-quality reports, helping you fine-tune every aspect of your report.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The correct answer is {{ 6 * pi }}.6 * pi is the source code and should be executed. Note here pi (π) is a constant in R.

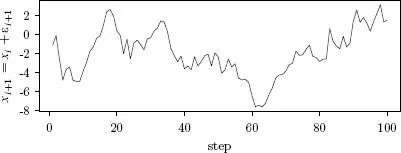

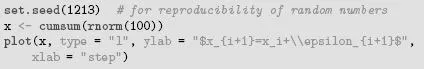

includegraphics{}. This is both tedious for the author and difficult to maintain — supposing we want to change the random seed in set.seed(), increase the number of steps, or use a scatterplot instead of a line graph, we will have to update both the source code and the output. In practice, the computing and analysis can be far more complicated than the toy example in Figure 1.1, and more manual work will be required accordingly.

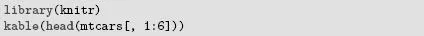

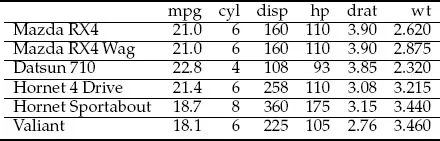

mtcars dataset: the first 6 rows and 6 columns.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Author

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Reproducible Research

- 3 A First Look

- 4 Editors

- 5 Document Formats

- 6 Text Output

- 7 Graphics

- 8 Cache

- 9 Cross Reference

- 10 Hooks

- 11 Language Engines

- 12 Tricks and Solutions

- 13 Publishing Reports

- 14 R Markdown

- 15 Applications

- 16 Other Tools

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app