- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Chinese City and Regional Planning Systems

About this book

While the Chinese planning system is vitally important to the rapid development which has been taking place over the past three decades, this is the first text to provide a comprehensive examination and critical evaluation of this system. It sets the current system in historical context and explains the hierarchy of government departments responsible for planning and construction, the different types of plans produced and recent urban planning innovations which have been put into practice. Illustrated with boxed empirical case studies, it shows the problems faced by the planning system in facing the uncertainty in the market economy. In all, it provides readers with a full understanding of a complex and powerful system which is very distinct from other planning systems around the world. As such, it is essential reading for all students interested in the current development taking place in China and, in addition, to planning students with a general interest in planning systems and theory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chinese City and Regional Planning Systems by Li Yu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Local & Regional Planning Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

China: An Introduction1

Planning in any country is inextricably linked with the history, politics and administrative structure of that country. Thus this introductory chapter is concerned with reviewing:

- the historical development of modern China;

- the social, economic, political and environmental issues that face the country today and with which the planning system is attempting to deal; and

- the system of governance.

This chapter will also explore the theoretical implication of the background for the planning system in China.

Introduction

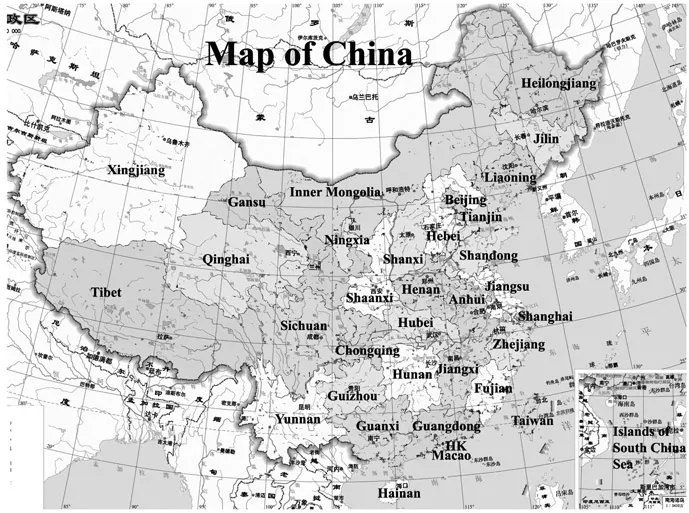

The People’s Republic of China (PRC), more commonly known as China, forms a major part of Asia. To the east it is bounded by the South and East China Seas, the Yellow Sea and the Korean Bay. Its land boundaries include Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar (Burma), Bhutan, Nepal, India, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Mongolia, Russia and North Korea, whilst it has sea boundaries with Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines in the South China Sea (see Figure 1.1).

China covers an area of 9,596,960 square kilometres. Within the territory, there was a population of 1.37 billion in 2010 according to the Sixth Census. China is the fourth largest country in the world after Russia, Canada and the United States.

The country is diverse in many respects. Climatically, it can range from tropical in the south to sub-arctic in the north. From a topographical perspective, China has deserts in the west; mountains and high plateaux in the central areas and coastal plains and deltas in the east. In term of ethnic groups, whilst the Han Chinese account for 91.9 per cent of the population, there are 55 minority groups such as the Zhuang, Uygur, Hui, Yi, Tibetan, Miao, Manchu, Mongol, Buyi, Korean, all of which account for the remaining 8.1 per cent of the population. As a country with the largest population in the world, there are different local dialects, e.g. Cantonese, Wu (Shanghaiese), Minbei (Fuzhou), Minnan (south Fujian Province-Taiwanese), Xiang, Gan and Hakka, being spoken as well as minority languages, but Mandarin is the most popular and common language.

Figure 1.1 Map of China

China is well endowed with natural resources, with plentiful supplies of coal, iron ore, petroleum, natural gas, mercury, tin, aluminium, lead, zinc and uranium, and has the world’s largest potential for hydropower.

The rapid economic development of the last three decades has resulted in environmental costs – notably air pollution from greenhouse gases and sulphur dioxide particulates. These were a consequence of a dependence on coal, acid rain, water shortages, particularly in the north, and water pollution from untreated waste and deforestation. In addition it is estimated that since 1949 one-fifth of agricultural land has been lost to soil erosion, economic and urban development and the encroachment of deserts. In 1993, 10 per cent of the land was given over to arable crops; 43 per cent to permanent pastures; 14 per cent to forest and woodlands and 33 per cent to other uses with 498,720 square kilometres being irrigated.

China has a long and impressive cultural and scientific history. It was unified as a nation under the Qin Dynasty in 221 BC; the succeeding dynasties were Han, Three Kingdoms, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties, Five Dynasties, Song, Yuan, Ming, with the last dynasty, Qing, being replaced by the Republic of China (ROC) in 1911. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was established on 1 October 1949 following a revolution led by Mao Zedong.

Physical Characteristics

China covers approximately 3.7 million square miles (9.6 million square kilometres), including Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau (Special Administrative Regions – SARs). From north to south (Heilongjiang to the South China Sea Islands) it covers 49 degrees of latitude; from east to west (Heilongjiang to Xianjiang) it extends over 62 degrees of longitude.

China’s topography is divided into a three-step staircase descending from west to east. The Qinghai-Tibet plateau is the top step, with an average height above sea level of 12,000–15,000 feet (4,000–5,000 metres); the second step consists of the Sichuan basins and the Inner Mongolian and Yunnan-Guizhou plateau with a height of between 3,000 and 6,000 feet (1,000–2,000 metres), and the lowest step, which is generally below 1,500 feet (500 metres), includes a belt of plain land in Manchuria, and north China; the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze, and the Yellow, Huai and Pearl rivers all of which flow east to west. The bulk of the Chinese population and most of its important cities are located in the area covered by the third step.

Given the size of the country and its varied topography China has a diverse climate. In northern China, where Beijing is located, the climate is typically continental with warm to hot summers and freezing cold and frosty winters which bring occasional light snow, whilst in the extreme northeast winters are cold enough to freeze the rivers for up to six months, and summer temperatures are also cooler, with humid conditions and high rainfall. The annual average temperature in Beijing is 11.8 degrees Celsius, with a low of −4.6 Celsius in January and a high of 26.1 Celsius in July. The annual average rainfall is 24 inches (619 mm).

Along the Yangtze River, where Shanghai is located, it is warmer than the north in both summer and winter but it can rain at any time. Winter weather is very changeable, alternating between spells of heavy rain and bright but cold and frosty periods with occasional snow. The main rainfall occurs during the summer months whilst along the coast from July to October typhoons (tropical cyclones) occur with strong winds and very heavy rainfall. The annual average temperature in Shanghai is just over 16 degrees Celsius, whilst the annual average rainfall is 45 inches (1,135 mm).

Southern China, which includes Guangzhou, Guangxi and Fujian, is the warmest and wettest part of the country in the summer because of its proximity to the tropics whilst the winters are mild. However, the inland region of southern China is mountainous with cooler summers and rain in the highlands and sunny and warm winters with little rain. The average annual temperature of Haikou, the capital of Hainan Island, is 24 degrees Celsius, whilst the annual average rainfall in the Yangtze River basin varies between 39 and 78 inches (5,600 mm).

Southwest China, which consists largely of the high plateau of Tibet, experiences extremely cold and frosty winters and warm and rainy summers whilst northwest China (Xianjiang) is predominantly desert and has very hot summers and bitterly cold winters made even more severe by icy winds. Rainfall is light. The average annual temperature of Urumqi, the capital of Xianjiang, is 7 degrees Celsius whilst the average annual rainfall in Inner Mongolia, Xianjiang and the Qinghai-Tibet plateau is 8 inches (200 mm) (Harding 1996).

The Development of Modern China

China: 1840–1911

It is not possible fully to understand modern China without an appreciation of its historical, cultural, economic and political development. This section aims to provide a brief understanding of the development of contemporary China, concentrating on the period from 1890 to the present day. For centuries a characteristic feature of China was a long established ideology and culture with supportive institutions, including:

- centralized imperial rule;

- Confucianism;

- an agrarian economy;

- a family centred social security system;

- self sufficiency; and

- traditional feelings of the superiority of the Chinese race.

This ideology and culture developed through the control of successive dynasties starting with the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties of the ‘ancient era’. The recorded history of China began in the fifteenth century BC when the Shang Dynasty used graphic markings that evolved into the present Chinese characters. City-states grew up in the Yellow River valley, which saw the beginnings of the development of Chinese civilization. 221 BC is commonly accepted as the year in which China was first unified as a large kingdom or empire under the Qin Dynasty. Successive dynasties developed bureaucratic systems that enabled the emperor to control an increasingly large territory that reached its maximum under the Yuan (Mongolian) and Qing (Manchurian) dynasties before the Republicans secured power in 1911.

It is generally accepted that in its development China alternated between periods of political unity and ‘separatism’, and at times it was dominated by foreigners, most of whom were eventually assimilated into the Han Chinese population. The influx of cultural and political influences from many parts of Asia, carried by successive waves of immigration, expansion and assimilation, eventually merged to create the Chinese culture.

Yet, despite its history of bureaucratic control and cultural development China entered the nineteenth century in decline and crisis for a couple of reasons, namely, the Manchu monarchy and the Qing Dynasty were unwilling to adapt to the rapid changes occurring in the outside world. These included adapting to industrialization; a large rural economy, although a few urban areas were beginning to industrialize, e.g. Shanghai, and the majority of Chinese being illiterate and leading their lives according customs and practices that had operated for centuries.

The First Opium War (or the First Anglo-Chinese War) between 1840 and 1842 is significant in Chinese history. Five treaty ports were opened for trade, and Hong Kong Island was ceded to the United Kingdom as a result of the ‘Treaty of Nanking’ in 1842 after the war. The First Opium War marked the beginning of modern Chinese history. China had declined and been invaded by the foreign powers. This greatly impacted the policies of the Chinese government after 1949, typically since China started its open door and reform policy in the 1980s. Chinese people and government have been struggling to be stronger in terms of the economy. Economic development is regarded as top priority.

The defeat of China by the Japanese in 1894–5 further established quite clearly the nature and extent of China’s decline. It resulted in the loss of Taiwan. The defeat of China by Japan highlighted the success of the Japanese industrialization policies at the same time as highlighting the failure of China’s attempts to modernize. As a consequence, there were attempts to introduce reforms, such as making the Manchu monarchy a constitutional democracy. The failure of China in the war with Japan in 1894–5 led to a new round of foreign powers scrambling for concessions in China.

The Boxer Rebellion in 1900 (Esherick 1987) had ultimately weakened the Qing Dynasty and paved the way for the republican movement. ‘Ultimately it was a question of overhauling a civilization rather than reforming a state; a case of rejecting overpowering tradition and searching for new forms of legitimacy outside it – and therefore outside China’ (Hutchings 2001: 4). Reforms were subsequently introduced which questioned the centralizing ideology that had underpinned Chinese society and government for centuries, including reforms to:

- education, when, in 1905, the Imperial Court abolished the traditional education system which had trained the elite and replaced it with a more open and questioning system based on principles that operated in the Western world;

- administration, which abolished the old centralizing boards and replaced them with ministries which took a proactive role in their areas of responsibility, such as the development of industry, trade and railways;

- the constitution, which established provincial assemblies in 1908.

Despite the fact that these reforms were substantive, they were primarily introduced in a final attempt to save the Qing Dynasty and the Manchu monarchy, and were not implemented with enthusiasm. Indeed their introduction was simultaneously accompanied by attempts on the part of the Qing Dynasty and the monarchy to reassert control over the provinces and concentrate power in the hands of the Manchu. These moves inevitably antagonized large sections of the population and led to the establishment of a republican revolutionary movement led by Sun Yat Sen, which in 1911 successfully ended imperial rule.

Revolution 1912–28

In 1912 the newly established Republic of China (ROC) appointed Sun Yat Sen as president, and established a parliament which met in Nanjing. Although the Manchus had made some progress with their reforms in the period 1900–11, including the emergence of an industrial structure in Shanghai, Tianjin, Wuhan and the northeast provinces, and the construction of a modest network of roads and railways, the newly established ROC set an ambitious agenda to create new institutions based on ideas which departed from the traditional Chinese ideology, many of which were drawn from the West, to establish an understanding of and loyalty to these new ideas, to develop industry and trade, to improve transportation and communication and to improve and extend education. At the same time the ROC was faced with both external and internal difficulties including insecure international boundaries, with Russian expansion in Mongolia, British interference in Tibet, Russian and Japanese rivalry in northeast China, and the frustration surrounding the ‘International Question’ with the Chinese nationalists wanting the economic privileges enjoyed by foreigners to be removed but the foreigners not being prepared to relinquish their privileges, and weaknesses arising from the existence of regional armies which were controlled by Yuan Shikai (an important warlord) and not the ROC.

In 1912 Yuan Shikai succeeded Sun Yat Sen as president of the ROC. As president, Yuan Shikai defeated the nationalists (Kuomintang) in 1913 and drove its leaders into exile, including Sun Yat Sen. Yuan Shikai attempted to revive imperial rule with himself as emperor. However Yuan died in 1916, 88 days after becoming emperor. However, his militarization of politics continued in the years after his death, with warlords effectively governing the territories they controlled, despite the existence of a central government. Indeed the lack of a credible central authority made national development impossible. In the words of Hutchings: ‘China needed unity – and the strong government armed with powerful ideas and popular support required to impose it’ (Hutchings 2001: 6).

Student protests on 4 May 1919 at the continued refusal of the foreign powers to hand back to China the former German concessions in Shandong led to the establishment of a broad movement concerned to promote Chinese nationalism and a ‘new culture’ based on Western ideas of democracy, science and Marxism.

Marxism in particular appealed to China owing to the success of the Marxist revolution in Russia which suggested many parallels with China. At the same time China, with its search for unity and a new identity, was seen by the Soviet Marxists...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 China: An Introduction

- 2 Evolution of the Chinese City and Regional Planning System

- 3 The Government System and Administrative Framework for Planning and Development

- 4 Regional Planning and Regional Governance Innovation

- 5 Statutory City Comprehensive Plan

- 6 Statutory Regulatory Detailed Plan and Planning Norms

- 7 Non-Statutory Plan: Urban Development Strategic Plan

- 8 Land Use System, its Reform and Planning Management

- 9 Performance of Chinese City and Regional Planning System

- Bibliography

- Index