eBook - ePub

Management and Competition in the NHS

Chris Ham

This is a test

- 132 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Management and Competition in the NHS

Chris Ham

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This second edition reviews recent reforms and the likely impact of future developments in management and competition in the NHS. In particular, it reflects the growing importance of primary care and the continuing debates about health care rationing. It concentrates on the realities and how they can be interpreted to help strategists, managers, clinicians, students and those supplying the NHS understand the mechanism of efficient health care delivery.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Management and Competition in the NHS an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Management and Competition in the NHS by Chris Ham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Service Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 The Background to the NHS Reforms

The establishment of the NHS in 1948 was a bold attempt to make health services available to all citizens through a system of public finance and public provision. It was universal in its coverage and sought to be comprehensive in terms of the services that were available. To encourage the use of these services, there were no charges for treatment, at least initially, and it was the aim of the founders of the NHS to ensure that all necessary services were readily accessible in each area. The principle of equity was firmly enshrined in the structure of the NHS, meaning that care was to be provided on the basis of clinically defined need rather than ability to pay or other considerations. NHS finance was raised through a combination of taxes and insurance contributions, in the course of time supplemented by nominal charges for prescriptions, dental treatment and eye tests. A private health care sector continued to operate alongside the NHS but it remained a minor part of total health service finance and provision until the 1980s when it grew rapidly in response to the constraints imposed on the NHS.

The NHS in the 1980s

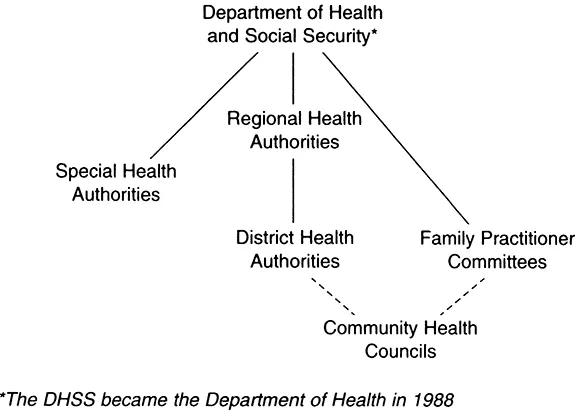

It was in the 1980s that the future of the NHS came under the critical scrutiny of Margaret Thatcher’s governments. Administrative reorganizations in 1974 and 1982 sought to tackle weaknesses in the organization and management of health services whilst preserving the basic framework that had been put in place in 1948. Figure 1 illustrates the structure of the NHS in England as it emerged from the 1982 reorganization. In this structure, district health authorities were responsible for running hospital and community health services and family practitioner committees administered the contracts of GPs and other independent contractors. The performance of district health authorities and family practitioner committees was supervised by regional health authorities and the Department of Health and Social Security. The result was a classic example of a centrally directed planning and management system involving hierarchical relationships between different levels of management and increasingly sophisticated efforts to get the organization right.

Figure 1: The structure of the NHS in England, 1982-90 (Source: Ham (1992a)).

The first significant departure from this approach came with the Griffiths Report of 1983. This left the structure of the NHS unchanged and instead sought to respond to evidence of variations in efficiency and the lack of attention to quality through the introduction of general management. In essence, this was an attempt to make the NHS more businesslike (Roy Griffiths was Deputy Chairman and Managing Director of the Sainsbury’s supermarket chain) through the adoption of management methods drawn from industry. The Griffiths reforms reflected a wider set of changes in the public sector during this period designed to control the growth of public expenditure, ensure that there was value for money in the use of public funds, and improve the quality of public services.

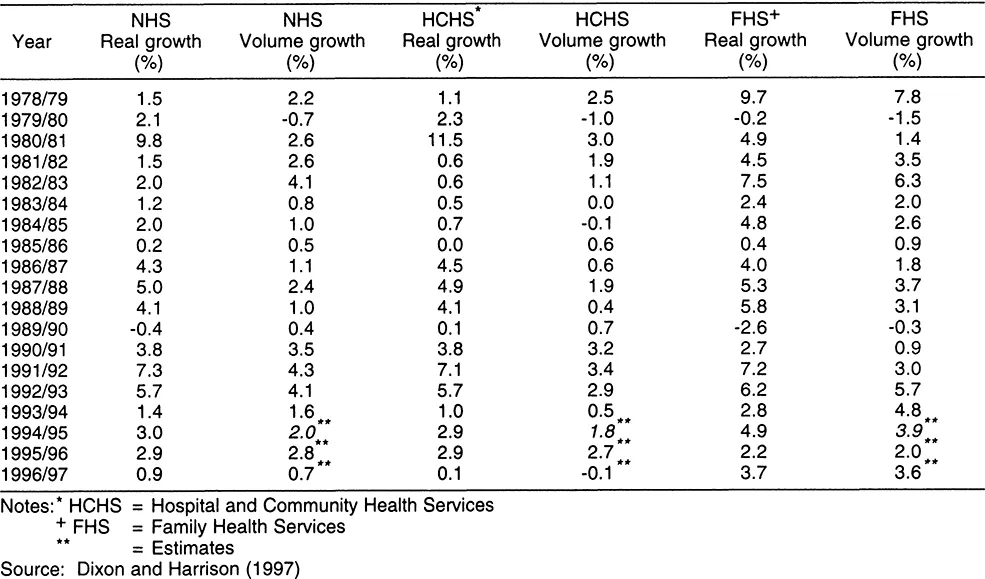

Throughout the 1980s expenditure on the NHS continued to grow in real terms but at a slow rate (see Table 1). As the decade wore on there was a widening gap between the money provided by government and the funding needed to meet increasing demands from an ageing population and advances in medical technology. The impact of the funding shortfall became particularly apparent during the course of 1987 and was felt most acutely in the hospital services (Ham, Robinson and Benzeval, 1990). In the autumn of that year, many health authorities had to take urgent action to keep expenditure within cash limits. This included cancelling non-emergency admissions, closing beds on a temporary basis, and not filling staff vacancies.

Behind these problems lay a funding system that failed to reward hospitals for treating extra patients. The so-called ‘efficiency trap’ was caused by the use of global budgets for hospitals that provided a fixed income regardless of the number of patients treated. This meant that hospitals were in practice penalized for productivity improvements because their expenditure increased in line with the number of patients treated but their income remained the same. In this situation, hospitals had little alternative but to reduce workload and cut costs when their budgets ran out.

The financial pressures facing health authorities were compounded by staff shortages. Media attention focused on Birmingham Children’s Hospital where the shortage of specialist nurses meant that a number of children had their heart operations delayed. The parents of two of these children, David Barber and Matthew Collier, resorted to legal action in an attempt to bring the operations forward, but to no avail. Doctors added their voices to patients, demanding that something should be done. The British Medical Association called for additional resources to avert the funding shortfall and, in an unprecedented move, the presidents of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons, Physicians, and Obstetricians and Gynaecologists issued a joint statement claiming that the NHS had almost reached breaking point and that additional and alternative financing had to be provided.

Table 1: Annual growth in NHS spending.

The government responded in two ways. First, in December 1987, Ministers announced that an extra £101 million was to be made available to the NHS in the UK to help tackle some of the immediate problems. Second, the Prime Minister decided to introduce a far reaching review of the future of the NHS. This decision was announced during an interview on the BBC TV programme, Panorama, in January 1988, and it was made clear that the results would be published within a year. The Prime Minister established and chaired a small committee of senior Ministers to undertake the review, which was supported by a group of civil servants and political advisors.

In fact, this was not the first occasion on which a review of the NHS had been undertaken. A working party comprising representatives of the Department of Health and Social Security, the Treasury, and the Health Departments of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, together with two specialist advisors with experience of the private health care sector, had reported on alternative financing methods in 1982. As the Secretary of State at the time, Norman Fowler, explains in his memoirs, the government decided not to move away from a system in which the NHS was financed largely from taxation, on the basis of the working party’s report. This was because other European countries were faced with similar problems to the UK and a centrally run and centrally funded health service like the NHS appeared to be most effective in controlling costs (Fowler, 1991).

In the absence of any specific proposals to change the basis of health service financing, Ministers pursued a policy of achieving greater efficiency in the NHS and encouraging the growth of private finance and provision alongside the NHS. The result was an expansion in the number of people covered by private health insurance schemes and in the role of private providers. By 1989, 13 per cent of the population in the UK was covered by private insurance. In parallel, the growth of private providers meant that by the end of the 1980s, eight per cent of all acute in-patients were treated privately and 17 per cent of all elective surgery was performed in the private sector. There was an even more rapid expansion of private residential and nursing home provision for elderly people and other vulnerable groups. Taken together, these changes meant that by the end of the decade private and voluntary hospitals and nursing homes supplied an estimated 15 per cent of all UK hospital based treatment and care by value (Laing, 1990).

The Ministerial Review

The Ministerial Review, initiated by Margaret Thatcher in 1988, offered an opportunity for alternative methods of financing and provision to be re-examined. The difficulty facing the government in this respect, as Norman Fowler indicates again, was that the NHS performed well when viewed in the international context. Total expenditure on health care, at around six per cent of GDP, was low by comparative standards, and yet for this spending the entire population had access to comprehensive services of a generally high standard. National planning meant that all parts of the country had access to health care, and a well developed system of primary care resulted in many medical problems being dealt with by GPs without the need to refer patients to hospitals. All this was achieved with only a small proportion of the budget being spent on administration (Ham, Robinson and Benzeval, 1990).

While problems clearly existed in relation to waiting lists for some treatments, poor quality of care provided for the so called priority groups, and lack of responsiveness to service users, they did not amount to a decisive case against the NHS. Rather, they indicated the need for a programme of reforms which retained the strengths of the NHS while the weaknesses were tackled. Indeed, for many of those who contributed to the debate, the most urgent requirement was extra money for the NHS to enable the changes that resulted from the Griffiths Report to be seen through. According to this school of thought, the key problem confronting the NHS was chronic and long term underfunding; there was nothing wrong with the structure of the NHS that additional resources would not overcome.

From this perspective, the control of health services spending exercised by the Treasury and seen by Norman Fowler as one of the strengths of the NHS, was in fact a major weakness in failing to deliver the volume of resources needed to fund the NHS to an adequate level. At a time when controlling public expenditure was an overriding political priority, it was not surprising that government Ministers were not persuaded by this argument, citing variations in performance across the NHS in support of their argument that existing budgets had to be used more efficiently before extra expenditure on the NHS could be justified (Lawson, 1992).

In its early stages the Ministerial Review focused on alternative methods for financing. This included looking again at the scope for increasing the role of private insurance and moving from tax funding to a social insurance system on the Western European model. Commenting on this aspect of the Review, Nigel Lawson notes in his memoirs:

‘we looked ... at other countries to see whether we could learn from them; but it was soon clear that every country we looked at was having problems with its provision of medical care. All of them – France, the United States, Germany - had different systems; but each of them had acute problems which none of them had solved. They were all in at least as much difficulty as we were, and it did not take long to conclude that there was surprisingly little that we could learn from any of the other systems. To try to change from the Health Service to any of the sorts of systems in use overseas would simply be out of the frying pan into the fire’ (Lawson, 1992, p616).

The examination of alternative methods of financing was soon superseded by an analysis of how the delivery of services could be reformed, assuming the continuation of tax funding. It was on this basis that ideas put forward by an American economist, Alain Enthoven, caught the attention of Ministers.

In a report published in 1985, Enthoven argued that an internal market should be developed within the NHS and this idea was elaborated by a number of right-wing think-tanks in their input to the Review (Enthoven, 1985). The contribution of Enthoven’s thinking was later acknowledged by Kenneth Clarke who said that he liked Enthoven’s idea of the internal market:

‘because it tried to inject into a state-owned system some of the qualities of competition, choice, and measurement of quality that you get in well-run, private enterprise’ (Roberts, 1990, pl385).

It was Clarke who played a major part in the final stages of the Review and who was responsible for presenting the government’s proposals following publication of the white paper, Working for Patients, in January 1989 (Secretary of State for Health and others, 1989).

Working for Patients

In the white paper, the government announced that the basic principles on which the NHS was founded would be preserved. Funding would continue to be provided mainly out of taxation and there were no plans to extend charges to patients. Tax relief on private insurance premiums was to be made available to those aged over 60, at the Prime Minister’s insistence and against the advice of her Chancellor of the Exchequer (Lawson, 1992), but the significance of this was more symbolic than real. For the vast majority of the population, the NHS would continue to be the provider of health care and the government promised that access to care would be based on need. This was later reiterated by a future Secretary of State, Virginia Bottomley, in a speech to the British Medical Association:

‘the government’s commitment to the fundamental principles of the NHS has not wavered one jot . . . During the NHS Review, more radical actions were considered and rejected. They were thrown aside because they were incompatible with the sacrosanct principle of the NHS: that the care and treatment that the service provides should be available to any man, woman or child, on the basis of clinical need, regardless of the ability to pay’ (Department of Health, 1993a).

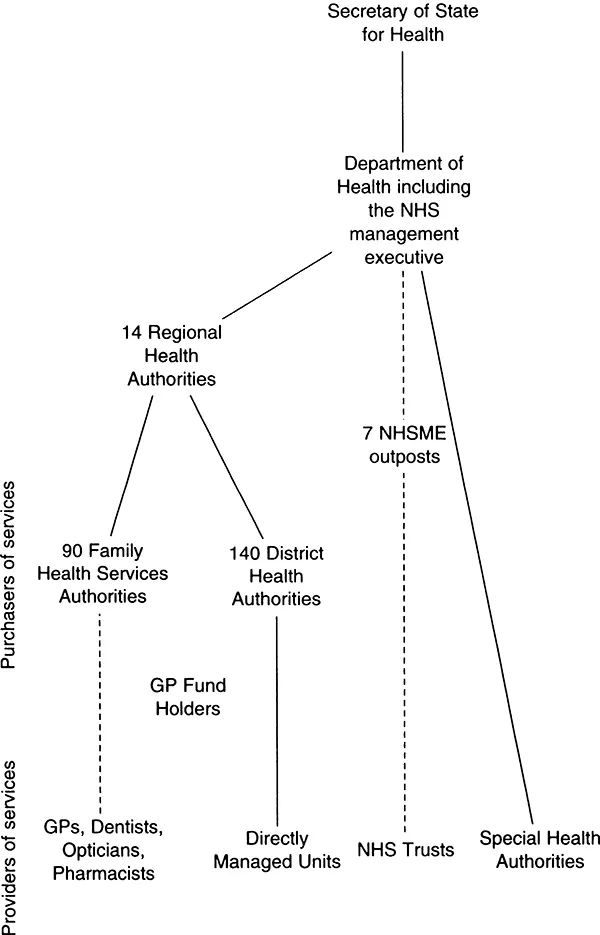

The main changes in Working for Patients concerned the delivery of health services. These changes were intended to create the conditions for competition between hospitals and other providers. This was to be achieved through a separation of purchaser and provider roles; the creation of self-governing NHS trusts to run hospitals and other services; the transformation of district health authorities into purchasers of services for local people; the opportunity for larger GP practices to become purchasers of some hospital services for their patients as GP fundholders; and the use of contracts or service agreements to provide links between purchasers and providers.

Fundamental to these proposals was that money would follow patients. This was intended to overcome the efficiency trap facing hospitals and to provide a stronger incentive than global budgets for hospitals to improve their performance. Ministers argued that a system in which providers had to compete for patients and resources would act as a significant stimulus to increase efficiency and to produce greater responsiveness to patients. The result would be a higher level of uncertainty on the part of providers about the source of their income but it was argued that this was necessary if the NHS was to tackle successfully the problems it faced.

These and other proposals were sketched in broad outline in Working for Patients, reflecting the speed with which the white paper had been produced. Subsequently, a series of working papers were published by the Department of Health containing more detail on different aspects of the proposed reforms.

Figure 2: The structure of the NHS in England after 1990.

Together with the parallel changes to community care planned by the government, the proposals in Working for Patients were incorporated in the NHS and Community Care Bill. This was published in November 1989 and received the Royal Assent in June 1990, paving the way for the NHS market to come into operation from April 1991.

The debate about Working for Patients and the NHS and Community Care Bill aroused strong feelings on all sides (Ham, 1992a). Opposition to the government’s proposals was led by the med...

Table of contents

Citation styles for Management and Competition in the NHS

APA 6 Citation

Ham, C. (2018). Management and Competition in the NHS (1st ed.). CRC Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1572578/management-and-competition-in-the-nhs-pdf (Original work published 2018)

Chicago Citation

Ham, Chris. (2018) 2018. Management and Competition in the NHS. 1st ed. CRC Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/1572578/management-and-competition-in-the-nhs-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Ham, C. (2018) Management and Competition in the NHS. 1st edn. CRC Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1572578/management-and-competition-in-the-nhs-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Ham, Chris. Management and Competition in the NHS. 1st ed. CRC Press, 2018. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.