![]()

1

Words

- 1.1 Words Being Spoken of Other Words

- 1.2 Voice, Music and Language

- 1.3 Voice

- 1.4 Music

- 1.5 Language

- 1.6 Lyric Synthesis

1.1 Words Being Spoken of Other Words

“When we use words we are always doing a disservice to ourselves.” With these words, Peter Brook (1999, xiv) reflects on their limitations and points toward a more inclusive language of theatre. Mendelssohn expresses similar misgivings in a famous letter to Marc André Souchay from 15 October 1842:

There is so much talk about music, and yet so little really said. For my part I believe that words do not suffice for such a purpose, and if I found they did suffice, then I certainly would have nothing more to do with music. People often complain that music is ambiguous, that their ideas on the subject always seem so vague, whereas every one understands words; with me it is exactly the reverse; not merely with regard to entire sentences, but also as to individual words; these, too, seem to me so ambiguous, so vague, so unintelligible when compared with genuine music, which fills the soul with a thousand things better than words. What the music I love expresses to me, is not thought too indefinite to be put into words, but, on the contrary, too definite. … [T]he words of one person assume a totally different meaning in the mind of another person, because the music of the song alone can awaken the same ideas and the same feelings in one mind as in another,—a feeling which is not, however, expressed by the same words.

(Mendelssohn, 2001, 276)

Steiner (1989, 19) says, “When it speaks of music, language is lame.” Similar concerns are echoed by sculptor Henry Moore (Wilkinson, 2002, frontispiece), who explains the trap of words as an artist, when he writes:

It is a mistake for a sculptor or a painter to speak or write very often about his job. It releases tension needed for his work. By trying to express his aims with rounded-off logical exactness he can easily become a theorist whose actual work is only a caged-in exposition of conceptions evolved in terms of logic and words.

If the relationship between artists and words is problematic, then the challenge to explore the synthesis between words and music, using words, compounds confusion over subject and object, frame and content. It is also challenging to attempt to explain what makes, for example, Purcell and Sondheim, Schubert and Kurtág extraordinary composers of vocal music, and to discover what they have in common, or not. That is what this book attempts to voice.

Words and music cohabit in the voice. Our voice is also our identity: an intimate way to communicate with others and a reason to be judged. It is arguably the most important part of our body that we take for granted. Our education system does little to shed light on its nature or use and prejudices the written over the spoken word. In consequence, our ability and vocabulary to describe or understand our voice is underdeveloped.

These words on words are not offered in apology but rather to warn the reader of limitations. This book is designed to be used by anyone who practices the associated disciplines: to help inform their decisions, even illuminate other possibilities. The words are a provocation to practice with voices through listening, rehearsing, conducting, directing, singing, speaking, writing, teaching, coaching, composing or making music. It is only through those activities that understanding and synthesis may take place.

1.2 Voice, Music and Language

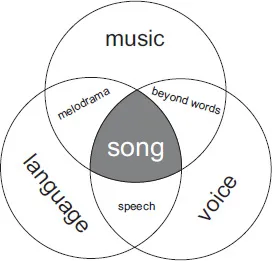

Voice, music and language are inseparable in our experience. Figure 1.1 illustrates their changing relationships with each other, their endless diversity and sophistication. Voice, language and music are tools of communication, but any two together provide specific modes: language and voice provide us with speech; music and voice provide us with sound beyond words, perhaps spiritual or pre-verbal communication, music and language provide us with melodrama. At the heart of the diagram, where all three circles meet, we encounter song, the most popular form of music in the world—potentially a unique synthesis of all the elements, which, at its best, transcends the sum of its parts: words and music become inseparable and embodied by voice. Zumthor (1990, 4) describes the integration of voice and language, beyond written text:

Figure 1.1 Voice/Music/Language: Song

The integration of a primordial symbolism and phonation is most evident in the use of language: it is also there that all poetry takes root. For researchers, voice and language are distinct anthropological objects. But a voice without language (a shout, voice control exercises) is not distinct enough to convey the complexity of the forces of desire animating it. The same impotence affects the language without voice, that is, writing. Thus our voices demand language and at the same time enjoy an almost perfect freedom of use vis-à-vis language. It culminates in song.

Zumthor proposes song as a summative activity for the voice, but we shall encounter evidence later to contest his proposition that a voice without language may not be distinct, or at least challenge some definitions of what constitutes language (see Chapter 5.7).

Whilst there is substantial evidence for the synthesis of voice, music and language, there is also an argument for their isolation. Our education system in the UK tends to promote division and difference over commonality and connectedness through over-specialization. Mary Midgley has been critical of this trend for several decades. In Science and Poetry (2001 ), Midgley places imagination central to human activity and thereby attacks the separation of the humanities from science. Later (2014, 29), she addresses a fundamental question of meaning:

A particularly strong assumption here has been scientists’ deep reliance on atomization; on finding the meaning of things by breaking them down to their smallest components. Atomizations illustrates the simplest, most literal meaning of the word “reduction”; it works by making things smaller. The illumination that follows does not, of course, flow simply from their being smaller but from the wider scientific picture into which they can now be fitted. That picture gives them a new kind of context, a wider whole within which they can be differently understood. And finding that kind of context is an essential part of what “understanding” means.

By equating specialization with reduction, she highlights a fundamental weakness in our thinking: without reference to the “wider whole” there can be no context for understanding. Reduction may lead to misunderstanding or prejudice between, for instance, theatre and music, or opera and musical theatre, or result in a prevalent academic dislocation between singing and speaking. Song is not only about words, not only about music and not only about the voice; it acts as a synthesis of all these aspects and possibly more, beyond the seven noted in Figure 1.1. One may see concerts, recitals, opera, music theatre and musical theatre as distinct genres, but any definition of them is reductive; too much has already been written about their apparent differences and status. A more useful context might be to try to understand their relationship as variants of the genus of song.

Music is a catalyst and able to generate synthesis across almost any discipline; insight into music is transferable across many platforms. However, the exchange is not always balanced in practice: composers who work with film, media, theatre or dance tend to know more about the art-form they work with than the directors of those art-forms know about music. Meanwhile, song—the ancient synthesis of singer, writer or poet and musician—may be suffering from academic neglect: there are few if any conservatoires where such a synthesis, such a transdisciplinary practice might be studied in its deserved wholeness and depth, practically, geographically, historically, socially and technically. The structure of our over-specialized education militates against it: music, language and voice?

Typically, the division of the arts into separate schools serves the funding structures of universities. It is predicated on division and competition above the value of collaboration, which Kohn (1992, 25) rails against in his education in the US: “The message that competition is appropriate, desirable, required and even unavoidable is drummed into us from nursery school to graduate school; it is the subtext of every lesson.” Such structures render collaboration as a challenge and synthesis as impossible.

The relationship amongst voice, language and music is the subject of this book, not the argument of primacy. The perspective this book holds on each of them is detailed in the following sections.

1.3 Voice

Our human voice is our identity; it defines us emotionally, intellectually and perhaps physically. As Steven Connor (2000, 7) says, “my voice is, literally, my way of taking leave of my senses,” a paradox that Connor elaborates further in terms of exteriority and interiority: “If my voice is mine because it comes from me, it can only be known as mine because it also goes from me.” Composing for singers emphasizes this paradox, as the instrument seems to be largely invisible: a technical discussion of laryngeal function may easily disguise the reality that the entire body is involved in singing; that same physical body has no independence from its intellectual and emotional life. When all the conditions are right, when all the elements are aligned to vocal synthesis, vocal communication may literally arrest us: great speeches may change history, and great vocal performances are seared into our memory. In these circumstances, we react viscerally, not merely rationally, as actors well understand.

Beyond identity and communication, our voice has a spiritual aspect. Connor points out that “hearing voices” may reflect on spiritual or religious experiences, indicate degrees of insanity, or belie the art of a great ventriloquist. From the beginning of Homo sapiens until the nineteenth century, disembodied voices were associated with these and similar phenomena. Then the twentieth century rendered vocal disembodiment commonplace through telephones, microphones, recordings, media and synthetic voices. In the twenty-first century, we are still learning to adapt to this exponential growth around us.

Clearly scientific, sociological, emotional, artistic and spiritual or religious considerations surround the voice, but composing for the voice requires practical understanding alongside, for instance, philosophy, technology, anatomy and psychology. Such considerations may not always function as a conscious part of the creative process, as Henry Moore warns, but this book aims to clarify and make such things available.

Much confusion and some prejudice persists over the concept of trained or untrained voices: there are no untrained voices. Each of our voices is trained through mimesis, a complex dialogue created between inside and outside worlds, through which our senses may discern knowledge. Damasio (2000, 318) proposes perception across the whole body: “The somatosensory modality … includes varied forms of sense: touch, muscular, temperature, pain, visceral, and vestibular.” This multi-sensory perception involves our voice, which learns, essentially, how to echo, copy, distort, transpose, create, instigate and play with the sounds and other objects around us. The human voice is the sound we are primarily tuned to, although there is disagreement as to whether that means speech (Vouloumanos and Werker, 2004) or music (Nakata, 2004), or if it is undifferentiated (Cevasco, 2008).

Despite its core importance, the voice is generally ignored by formal education, beyond encouraging some rudimentary aspects of uniform pronunciation. We all learn to speak by copying those around us; only actors and singers regularly carry out research, investigate and explore specific conscious physiological and psychological techniques. Alfred Wolfsohn, who established his Voice Research Centre in 1935, evinced how this educational neglect may have profound consequences. His work demonstrated how damage to our health can be the result of, and be cured by, a better understanding of our voice.

Children of all ages who are surrounded by people singing will more easily copy the sounds of those singing around them. Our earliest lessons in both song and speech may be born from mimesis, but just as an athlete may at some stage aspire to explore their body’s capacity through a specialist coach, a singer may seek professional guidance to develop an athletic aspect to the voice. To complain that a trained voice seems unnatural would be to suggest that athletes are unnatural. Both voices and athletes may, of course, be trained poorly. Unfortunately, some composers may be unaware of the athletic demands that they ask of a singer, which may result in the vocal equivalent of composing unplayable music for the violin. Moreover, composers may also be unaware of the potential of vocal damage that a singer must always be aware of, as the consequences may be catastrophic (Warner, 2017). Perhaps poor teaching results in more vocal damag...