![]()

Part 1

Planning

![]()

1Designing a secondary curriculum map

Before we can discuss the teaching of computing, we must first plan the material which we want to deliver. In most cases, this will involve designing a five-year curriculum map which outlines all the topics, skills, concepts and knowledge which a student will need to succeed in our subject. This may seem like a daunting task at first; however, having re-written an entire curriculum map based on the new national curriculum of 2013, I can assure the reader that this undertaking can be broken down into a series of procedural processes. This chapter will guide the reader through creating their own curriculum map, and the accompanying eResources contain a comprehensive five-year curriculum which can be used or adapted.

It is important to start the planning process with a firm grasp of the end point i.e. what does a student need to know or be able to do in my subject by the time they leave school? We can then plan backwards from this point. Perkins suggests that we need to understand what “playing the whole game” looks like in our subject (Perkins, 2009). Knight and Benson go on to suggest that it is useful to think about what it means to be an expert in our subject. (Knight & Benson, 2014). It is the clarity of this end goal – moving beyond creating a little living library on our subject to creating a student who through an apprenticeship has developed an understanding of how an expert within the domain, thinks, acts and communicates – that helps ensure our curriculum prepares pupils for expertise and not just the recital of content.

Being a computer scientist – what does this mean?

Computer scientists study, create and maintain computer systems to solve real-world problems. In order to do this, they must master a certain way of thinking and have an understanding of hardware and software. The emphasis of the previous ICT curriculum was on using software, for example office and multimedia applications. However, to be a computer scientist one is expected to not only know how to use software but also how to build one’s own hardware and software solutions.

To become an expert in computer science, our students will need to master a particular way of thinking and problem solving. This way of addressing problems is aptly called computational thinking and consists of the following key skills:

•Decomposition – the ability to break down a problem into smaller solvable parts.

•Logical reasoning – organising and analysing data logically, leading to the systematic application of rules to solve a problem.

•Abstraction – reducing complexity by hiding irrelevant details and focussing on the most important elements.

•Pattern matching – finding similarities between different problems.

•Generalisation – adapting a solution that solved one problem to solve another problem, that is, making one solution work for multiple problems.

•Algorithm design – planning a set of steps which detail how to solve a specific problem, represented in a form that can be effectively carried out by an information-processing agent.

•Prediction – hypothesising what will happen at each stage of an algorithm as it is computed and predicting how a human (or any living organism) will subsequently behave and react as they interact with the system.

•Testing and debugging – checking that programs work and are free from logic, syntax and runtime errors by using typical, erroneous and extreme data. Debugging is the process of fixing problems that arise out of testing.

•Evaluation and optimisation – through iterative development, continuously assessing a solution and improving it to ensure that the most effective and efficient combination of steps and resources have been used.

(Wing, 2006; CSTA, 2011; Zagami, 2013; Bagge, 2014; Code.org, 2014; Selby & Wollard, 2014; White, 2016; Papert, 1980)

It is important to note that computational thinking is distinct from other ways of thinking and solving problems and so our curriculum needs to be designed to develop these particular ways of approaching and solving problems. Wing stresses the importance of computational thinking. As a follow-up, Wing goes on to state that the expert computer scientist therefore is someone who chooses the right abstractions and the right tool(s) to automate and mechanise a task (Wing, 2008). Whilst the computer scientist uses logical reasoning, the computer scientist is not merely thinking like a machine; the thought process is creative and considered. In solving problems and designing systems, the computer scientist also has to be aware of human behaviour and the hardware which their programs will run on. Whilst we refer to this way of thinking as computational thinking’, it can only be achieved by a human and this ability to work at different levels of abstraction is the true sign of an expert in computer science.

It is worth contrasting the expert skills in computer science, with those in IT. Many of these skills are covered to an extent by the remaining Level 2 and 3 vocational qualifications in IT, for example BTEC diplomas, technical awards and IT qualifications (ITQs). Whether you choose to deliver these vocational IT qualifications at Key Stages 4 and 5 or not, it would be prudent to think about these skills when you are planning your Key Stage 3 curriculum. Developing a solid IT skillset at Key Stage 3 will certainly benefit students across their other subjects at Key Stage 4 and will also be essential for most careers. The following list of expert IT skills is not exhaustive and would require that the person had already developed digital literacy skills as previously outlined in Table 0.1:

•Select, combine and use office and multimedia applications appropriately.

•Select and use hardware and software appropriately.

•Use digital tools to communicate and collaborate effectively.

•Understand and use cloud computing effectively: software as a service, platform as a service and infrastructure as a service.

•Present data and information for a given audience and purpose.

•Perform web-based research and the evaluation of sources.

•Manage complex projects with time, cost and resource constraints.

•Understand and consider the social impact of IT.

•Comply with and be able to advise on the following legislation: computing, intellectual property, copyright and licensing.

•Setup, maintain and manage computer systems.

•Evaluate solutions critically.

(Department for Education, 2013; The Learning Machine [TLM], 2016)

It is evident from this list that the skillset of an IT expert is quite broad. Most IT experts will specialise in a particular area after having developed their expert practice through a combination of professional certifications, qualifications and employer-based training. Our remit as computing teachers is to ensure that students are exposed to these IT skills and to ensure that students are equipped with the IT skills that they need for the future world of work. The programme of study for Key Stage 4 explicitly states that “All pupils must have the opportunity to study aspects of information technology and computer science at sufficient depth to allow them to progress to higher levels of study or to a professional career” (Department for Education, 2013).

For the purposes of this book, we will be referring to both the computer science expert and the IT expert. As we refer back to “playing the whole game” or the big picture, we will be referring to the skills in both strands, that is, the computing expert.

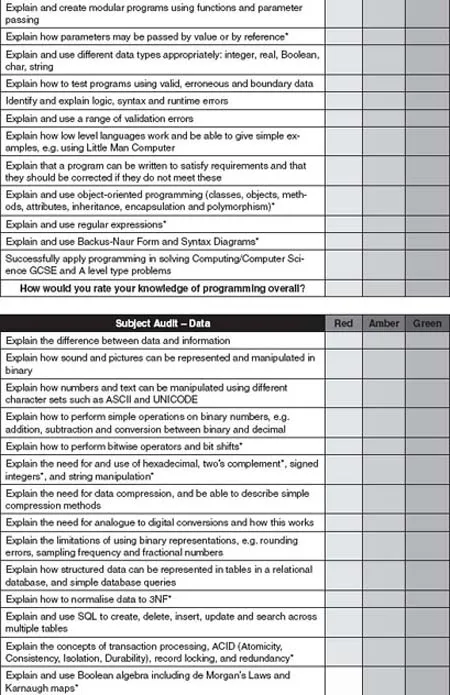

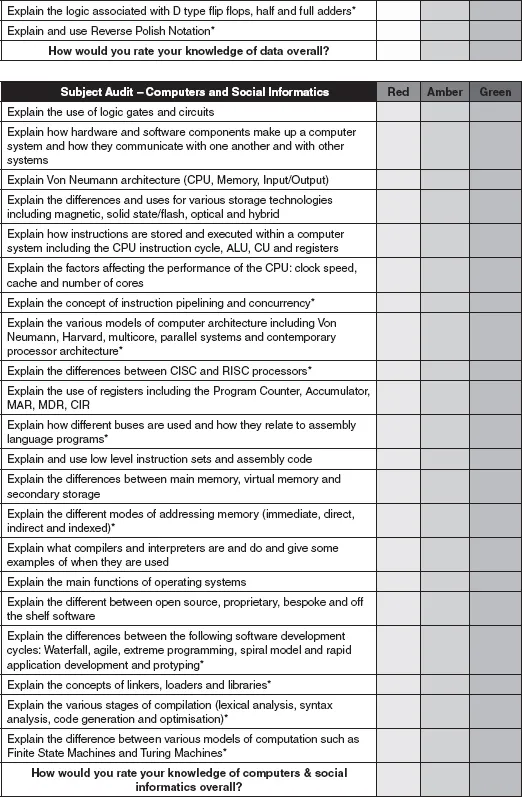

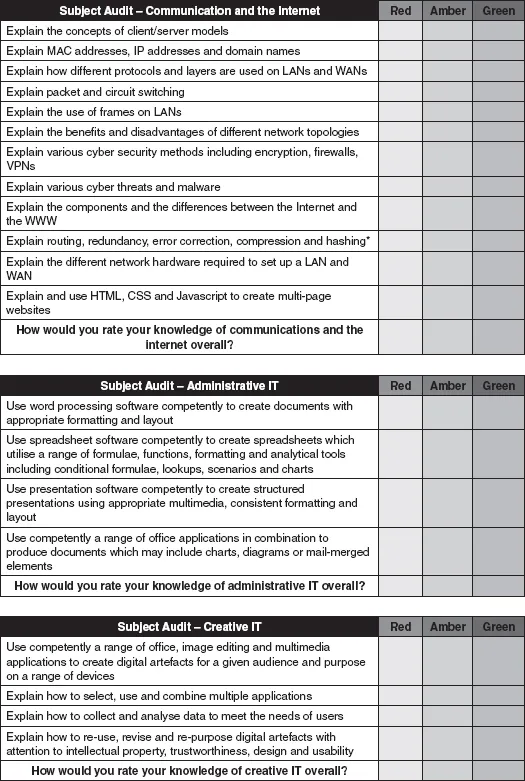

Shaun Lloyd created a useful subject audit for computing under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 Licence (Lloyd, 2015). Mark Dorling and Abigail Woodman also developed a computing skills and knowledge audit tool for the CAS QuickStart Computing continuing professional development (CPD) toolkit for secondary teachers (Dorling & Woodman, 2015). These have been modified to include IT and DL strands in Figure 1.1 on the following pages:

Figure 1.1Subject knowledge audit for computing. This is a derivative work based on documents published on the CAS community website (Lloyd, 2015; Dorling & Woodman, 2015; Kemp, 2014; Sentance et al., 2017).

All teachers should be encouraged to complete a subject knowledge audit on an annual basis to identify three targets for development. In Coe et al.’s. influential report What Makes Great Teaching, they identified six characteristics of great teaching. The first characteristic which had strong evidence of a positive impact on student outcomes was teacher (pedagogical) content knowledge (...